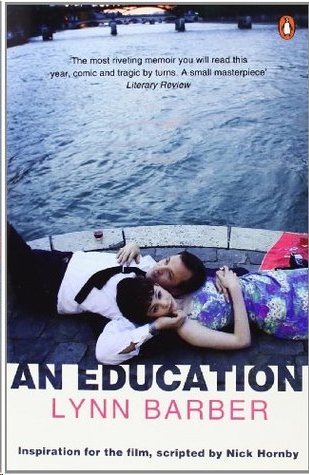

An Education

Authors: Lynn Barber

Tags: #Journalists, #Publishers, #Women's Studies, #Editors, #Personal Memoirs, #Women, #May-December romances, #Women Journalists, #Biography & Autobiography, #Social Science, #General

An Education

Lynn Barber studied English at Oxford University. She began her career in journalism at

Penthouse

, and has since worked for a number of major British newspapers and for

Vanity Fair

. She has won five British Press Awards and currently writes for the

Observer

. She has published two volumes of her celebrated interviews,

Mostly Men

and

Demon Barber

.

By the same author

How to Improve Your Man in Bed

The Single Woman's Sex Book

The Heyday of Natural History

Mostly Men (collected interviews)

Demon Barber (more interviews)

An Education

LYNN BARBER

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published 2009

1

Copyright © Lynn Barber, 2009

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

‘Tarantella’ by Hilaire Belloc from

Sonnets and Verses

(© The Estate of Hilaire Belloc 1923) is reproduced by permission of PFD (

www.pfd.co.uk

) on behalf of The Estate of Hilaire Belloc.

An extract from ‘Sea Fever’ by John Masefield is reproduced by permission of The Society of Authors and the literary representative of the Estate of John Masefield.

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-193226-2

For Rosie and Theo

Preface

In 2002, I was chatting with a friend, a fellow journalist, when he happened to mention Peter Rachman, a notorious evil landlord in Fifties London. He started to explain who Rachman was, but I interrupted, ‘Oh yes, I knew him slightly, when I was at school.’ My friend was incredulous: ‘You knew Rachman? When you were at

school

?’ So then I explained that, while I was still at school, I had this much older boyfriend, Simon, who was in the property game and that we sometimes went round to see Peter Rachman (though we called him Perec, his original Polish name) at his various nightclubs. Telling it baldly, like that, I could see it sounded barely credible, and when my friend kept asking questions – sceptical questions, as a good journalist should – I gave up the attempt to explain and changed the subject.

But afterwards I found myself thinking long and hard about Simon for almost the first time in forty years. I hadn't exactly

repressed

the memory, but I had effectively banished it to the very back of the cupboard. It was something I didn't like thinking about, didn't like talking about, saw no point in remembering. It was as if, say, I'd had a nasty car accident as a teenager which entailed many horrible operations but luckily I had made a full recovery so why go back over the gory details? There was no pleasure in remembering Simon so I preferred not to.

But then the Rachman conversation got me thinking, ‘Well yes it

was

very odd that I knew Rachman when I was only sixteen.’ But the more I thought about it, the more everything about my life as a teenager seemed odd. Why was I, a conventional Twickenham schoolgirl, running round London nightclubs with a conman? Why did my parents let me? Almost to explain it to myself, I wrote down everything I could remember and found that, once I tapped this untouched spring of memory, there was no stopping it. So then – being a great believer in Dr Johnson's adage that no one but a blockhead ever wrote except for money – I shaped it into a short memoir and sent it off to my friend Ian Jack, who was editing

Granta

magazine. He had asked me to write an article on my love of birdwatching so ‘An Education’ must have come as a surprise, but anyway he published it in the spring of 2003. You can find a slightly revised version of it here, in chapter two.

Soon after the

Granta

piece appeared, my agent contacted me to say she'd had an approach from a film producer called Amanda Posey who wanted to meet me to discuss making a film of ‘An Education’. It was the worst possible timing – my husband was in the Middlesex hospital having a bone marrow transplant and I was virtually living in the hospital. But Amanda Posey said she would come to a nearby coffee bar and meet me any time I could get away. So, rather begrudgingly, I left the Middlesex for half an hour to meet her and her partner, Finola Dwyer. Amanda struck me as a very bright young woman but so unlike my notion of a film producer (I was thinking Harvey Weinstein) that I almost suspected she might be a fantasist. She asked if I wanted to write the filmscript myself and seemed delighted when I said no – she said she already had a screenwriter in mind. The whole meeting seemed completely unreal but then everything at that time seemed unreal, so I said ‘Yes, by all means make the film,’ and went back to the hospital and forgot about her.

Months later I received a contract the size of a phone directory and realised that Amanda Posey was serious. I also learned that the scriptwriter she had in mind was her boyfriend – now husband – Nick Hornby. This made the whole idea more plausible, especially when I met Nick. I found it odd (still find it odd) that this preeminently ‘boy’ writer should so completely understand what it felt like to be a sixteen-year-old schoolgirl who was on the one hand very bright but on the other very ignorant about the world but, miraculously, he did. He even seemed to understand my parents, which is more than I could ever say myself.

Luckily I had the nous to put a clause in the contract saying I was allowed to see and comment on (but not alter) any script Nick Hornby wrote. This was an education in itself – as the years and drafts went on (I think there were eight in all) I learned a great deal about the art of screenwriting from watching Nick's scripts evolve. The first draft stuck very closely to my story which cruelly exposed the fact that it had no proper ending – it reached a dramatic climax and then dwindled away. Over the next few drafts he battled to create a good ending and eventually did; he also fleshed out characters who had been no more than names before and created whole scenes that were not in my story at all. The girl who used to be me became a cellist in the school orchestra, and bought a Burne-Jones at auction, and went to Walthamstow dog track, none of which I did, while her parents slowly mutated from infuriating dinosaurs into perfectly reasonable human beings. By draft eight I found myself actually weeping with sympathy for my father – a weird and possibly even therapeutic moment in my life. The only bad thing Nick did was to change Simon's name to David, which was my husband's name. I have changed it back to Simon (though that was not his real name either) in this book.

Years passed, draft screenplays came and went, possible backers came and went. I would have given up by year two, but Nick and Amanda and their partner Finola Dwyer persisted and eventually, last year, the film went into production. Amanda invited me to watch some of the filming, and then the first screening of the rough cut. I loved it and started talking proudly about ‘my’ film. But I was completely thrown when people kept asking me ‘How does it feel to see your sixteen-year-old self on screen?’ Is there any polite answer to that? I mean, how daft would you have to be to believe that an actress, albeit an exceptionally good one (Carey Mulligan) was your sixteen-year-old self? But it set me thinking about memory, which has never been my strong point, and trying to remember as much as I could before it vanishes for ever.

I am of an age (sixty-five) where most people start worrying about Alzheimer's and panicking if they forget a name. But I won't even notice when I get Alzheimer's because I've had such a flaky memory all my life. I can do short-term memorising. I can bone up for an exam or, nowadays, an interview by reading up the subject the day before and retaining it for precisely 24 hours but then – boof! – it's gone. That's why it's terribly embarrassing bumping into someone I've interviewed – they expect me to remember all this

stuff

about their lives, but of course I had to erase it to make room for the next interviewee. Nowadays I can't even always remember whether I've interviewed someone. Or, come to that, slept with someone. I am always a bit embarrassed meeting men who say they were my contemporaries at Oxford. Did we ever hit the sack, I wonder?

There are whole subjects I used to know that I have since forgotten. I have a certificate that says I can do shorthand at 100 wpm – how did I acquire that? Did I bribe the examiner? I got top marks in A-level Latin –

eheu fugaces

, I can't translate a line of Horace now. In my brief, improbable career as a sex expert, I wrote a manual called ‘How to Improve Your Man in Bed’ that was accepted at the time as an authoritative guide. How did I have the chutzpah to do it? I also spent five years researching and writing a book,

The Heyday of Natural History

, which involved reading all the popular natural history books of the Victorian era. Gone, all gone. I seem to have an auto-erase button in my brain that says that once I have ‘done’ a subject, I no longer need retain it. This is fine for my job, journalism, but not so good for real life. It hurts my friends' feelings that I don't remember conversations we had just weeks ago. ‘But I

told

you, Lynn!’ is a frequent cry. ‘I know, I know,’ I say quickly, ‘but it was so interesting I wanted you to tell me again.’

I have certain strategies for remembering. I have kept a daily diary ever since I was thirty (and patchily before that) so I can always look things up. Last year my elder daughter, pregnant for the first time, asked how long I was in labour before she was born. I had no idea, but found my 1975 diary, looked up 3 May and found – wow! – only two hours. If I'd told her only two hours, she wouldn't have believed me, but then I wouldn't have believed me either. But my biggest mainstay for most of my life was David, my husband, who remembered everything. Most usefully, he remembered people's names and when we'd met before and what we talked about, so he could often give me discreet prompts in social situations. But even he was shocked once at a dinner party when someone was talking about China and I said ‘Oh, I'd love to go to China!’ And he said, ‘But you did, Lynn. In 1985. You hated it.’ And everybody stared.

This is all by way of warning that you are in the hands of a deeply unreliable memoirist whose memory is not to be trusted. Where possible, I have checked facts either against my diaries or articles, but I'm never exactly a slave to facts at the best of times. But does it matter? Who owns memories after all? I once wrote an account of my Fifties childhood for the

Independent on Sunday

and my Aunt Ruth (Dad's sister) violently objected to my saying that I ate nothing but scrambled eggs on toast for a whole year. She said it was slanderous rubbish and a terrible slur on my mother. But how would Aunt Ruth know? We only saw her once a year at Christmas and presumably then I was eating turkey. My mother, typically, says she has no idea what I ate. She is ninety-two now, and remembers what she wants to remember, and forgets the rest. That seems fine by me.