Among the Bohemians (30 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

As sex definitions began to break down, Bohemia gave the all-clear to cross-dressing.

There were women with short hair, men with long; women wearing trousers, men in robes or tunics, and pierced ears for both sexes.

Earrings for men were to become as symbolic of the libertine as of the creative spirit.

A man wearing earrings was a gypsy, a pirate, a predator.

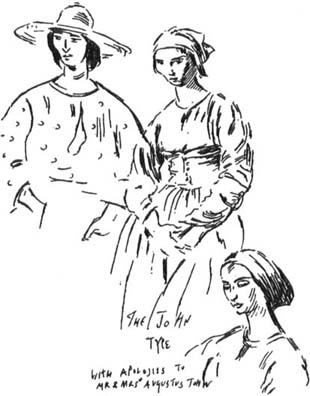

Here again, Augustus John was the living embodiment of the Great Bohemian.

You could pick on any aspect of his appearance and it would reinforce his pre-eminence in the field.

In 1917 a band of over thirty Slade girls in various stages of undress draped themselves across the stage of the Chelsea Palace Theatre and performed a history of artistic Chelsea as a benefit for the soldiers in France.

It ended with a rousing finale in praise of everyone’s Home Front hero – Augustus:

John! John!

How he’s got on!

He owes it, he knows it, to me!

Brass earrings I wear,

And I don’t do my hair,

And my feet are as bare as can be;

When I walk down the street,

All the people I meet

They stare at the things I have on!

When Battersea-Parking

You’ll hear folks remarking:

‘There goes an Augustus John!’

Lady Colin Campbell wrote in her book of etiquette in 1898, ‘It is not considered good taste for a man to wear much jewellery.’ But being an Augustus John was not about being tasteful or seemly.

Garish, flashy jewellery was part of the whole picture, for women as much as for men.

One of the great delights of this was that one could glitter and jingle in a profusion of bangles, ornaments and colourful fake beads without spending a fortune.

The urge to decorate oneself could be as easily satisfied with the purchase of a string of Woolworth’s pearls as with an emerald parure.

Big, ostentatious jewellery soon became part of the uniform: there was Mary Butts with one jade pendant earring shaped like a mill wheel, and Nancy Cunard with her ‘signature’ ivory African bangles from wrist to elbow.

E.

M.

Delafield’s

Provincial Lady

(1930) spots the arty guest at a party the moment she walks through the door, from her ‘scarab rings, cameo brooches, tulle scarves, enamel buckles, and barbaric necklaces’.

The provincial lady disapproves, for there is something vulgar about such profusion.

But vulgarity was no longer off limits.

Make-up was the thin end of the wedge.

The Victorians saw rouge and lipstick as restricted to women of easy virtue.

Gwen Raverat remembered how as a child she wandered by mistake into the boudoir of an elderly lady and found, to her horror, a jar of face powder on her dressing table:

‘Could Mrs. H. really be respectable?’

A few women did use lip-salve, a pinkish cream which they applied with the excuse that it moisturised their lips, but Gwen’s own mother never used make-up of any sort, and she knew that only very wicked, fashionable women, or worse still, actresses, ever applied rouge or lipstick.

Thus the merest touch of green eye-shadow, not to mention more dramatic effects caused by chalk-white face powder or scarlet ‘lip rouge’, provoked intense shock.

And then, as if revelling in their turpitude, these women smoked.

A favourite pleasure of the gypsies themselves, tobacco smoking had long been regarded by some male Bohemians as an activity of primary significance, almost a poetic initiation.

Like the smoking of marijuana in a later epoch, it was celebrated by Théophile Gautier’s romantic contemporaries in verse

and fiction.

Arthur Ransome placed talking, drinking and smoking together as the three indispensable pleasures of life – to be enjoyed in the company of ‘half a dozen honest fellows’.

But females were not content to be left out of such pleasures, and soon Ransome’s male havens were invaded by advanced women brandishing cheroots.

Ethel Mannin recalled how flagrant such behaviour seemed in those early years:

The year would have been 1916 or 1917, not later.

The girl, whose name I remember as Monica, gave me a De Reszke Turkish cigarette from a small packet, and there we two young girls viciously sat, with our pot of tea and our toasted scones,

smoking,

and

in public…

By the 1920s everyone was puffing at Turkish, Egyptian or Virginian cigarettes.

For women this was, as Mannin said, ‘the outward and visible sign of sex equality’.

One by one, the bastions were falling.

The sex divide would never be the same again.

*

Undoubtedly, the Bohemian in Britain was now emerging from the margins, and becoming an easily recognisable archetype, fitting neatly into a range of consistent models.

We can parade some of these ‘classic’ Bohemian fashions along a notional catwalk.

First, the stage dandy:

Nobody looks the part of a poet so well as Pound…

… writes an admiring observer of the American writer…

In his velvet coat, his open shirt with Danton collar, his golden beard, his long hair well brushed up and back from a high forehead, he suits the romantic conception of the poet…

Next, the droopy, home-made type: Helen Anrep, described by Angelica Garnett:

Of all our friends she was closest to what in those days was called bohemian, meaning unconventional and penniless.

She wore long, flowered dresses pinned at her bosom with a brooch, a shawl dripping from one shoulder, white stockings and little black shoes – rather as though she had stepped out of a picture by Goya or Manet.

Nina Hamnett, having her photograph taken with a poetess friend, personifies shabby chic:

I put on my ancient and historic trousers, which I had worn before the war at parties, with Modigliani’s blue jersey.

We thought that if they wanted a

real

picture of ‘Bohemia’ we would give them something really good.

Next, the Slade Art School meets the Café Royal – Kathleen Hale on one-armed ‘Badger’ Moody:

An archetypal Bohemian, he wore a waisted jacket secured by one button, immensely wide checked grey trousers, a silk scarf in lieu of a collar and tie, and a large black sombrero at a rakish angle.

And the show comes to its climax with the gypsy goddess herself, Dorelia.

Nicolette Devas reported that Augustus John encouraged his women to wear these clothes because he found contemporary fashions unpaintable.

Certainly he believed that women ‘should… attire themselves with grace and dignity without bothering about the fashion too much’.

Dorelia’s clothes were quintessentially ‘artistic’, and hugely influential,

producing an unmistakable ‘look’.

All the girls in Chelsea wanted to look like Dodo.

Carrington, Reine Ormonde, Sine McKinnon, Christine Kühlenthal, Viva King, Edith Sitwell, the John harem were all copying her full skirts and gypsy colours.

In Gilbert Cannan’s

Mendel

the artist Logan (alias John Currie) is looking for a new image for his girlfriend Oliver:

Cecil Beaton captures ‘the Dorelia look’ in

The

Glass of Fashion

.

‘How shall we dress her?’ asked Logan.

Mendel took out his sketch-book and drew a rough portrait of Oliver in a gown tight-fitting above the waist and full in the skirt.

‘I should look a guy in that,’ she said.

‘It’s nothing like the fashion.’

‘You’ve done with fashion,’ said Logan.

‘You’ve done with the world of shops and snobs and bored, idiotic women.

You’re above all that now.

In the first place there won’t be any money for fashion, and in the second place there’s no room in our kind of life for rubbish.

You’re a free woman now, and don’t you forget it, or I’ll knock your head off.’

So influential were Dorelia’s clothes in Bohemia that Cannan safely assumes his readers cannot fail to recognise her unique style in Mendel’s sketch.

Not to be outdone, the males of the species emulated Augustus, and strode around the Slade in capes, black hats and soft collars looking like Courbet.

There are many more variants, all of them different, all of them Bohemian.

And what partly defines them as Bohemian is that they have all ‘done with fashion’.

Not one of these looks features in the procession of shifting hemlines and changing silhouettes that is the accepted history of twentieth-century costume.

*

Where does fashion fit into the Bohemian world view?

Standards of fashion, like standards of female beauty, are notoriously relative, capricious and hard to nail down.

It takes a confident, iconoclastic vision to see behind the current modes, to brave charges of heresy against the fashion elect who ordain women’s perpetual discontentment with their self-image.

There was an attitude among nineteenth-century intellectuals that subservience to fashion was the worshipping of false gods, therefore to take pleasure in dress was sinful.

One’s

duty,

however, was to dress well and appropriately, without display, and according to one’s class.

The Rational Dressers moved beyond this: their emphasis on comfort, hygiene and woollen underwear made fashion at best an irrelevance, at worst a tyrant.

Bohemians inherited elements of both these attitudes, but introduced a number of other unquantifiable ingredients.

There is no single summing-up of such

an eclectic attitude to dress, and yet one could recognise the type at twenty paces.

As with their relationship to interior design, artists were highly aware that they were running risks by creating an image.

Where your orange decor might be safely regarded as being outside public consumption, your apparel proclaimed you the minute you set foot in the street.

How you looked, what you wore, was not a peripheral issue, and Bohemians knew it.

But it could be hard to know which way to turn.

If you marched to the beat of a different drummer, should you break step as soon as the trendy horde caught up with your unique self-created look?

If you cut your hair short in protest at fancy female coiffures, did you grow it again when the flappers and shopgirls all cut theirs?

If you were truly artistic did you, when hemlines soared, retreat into long full dresses?

Artists of integrity felt that they stood outside the fashion rat race, but they still had to decide what to put on each morning, and it was not always either helpful or desirable to stand out from the crowd.

There is a story of how one night at the Café Royal, Augustus John, C.

R.

W.

Nevinson, Mark Gertler, Horace Cole and John Currie were drinking together when Cole chanced to overhear some bookies making derogatory comments about their appearance.

In no time at all a tumultuous brawl broke out which left the Café knee-deep in soda water and broken glass.

After the mess had been cleared up, the management decreed that, in future, artists were to be barred from the Café.

The next day when Nevinson strolled by for his customary drink he was refused entry.

Indignant, he went elsewhere, for he had not been personally involved in the fight.

Two days later he came up to town and in due course presented himself at the Café Royal.

To his astonishment the commissionaire let him in without a murmur – surely the ban hadn’t been lifted?

‘Oh, no, sir.

But it only applies to artists.’ It took Nevinson some time to deduce that, having set out to town that morning, he was dressed in a suit and bowler hat.

And for the porter, that meant he was not an artist.

The caricature image of the artist, so prevalent in the pages of

Punch,

made some of them perversely eager to shake it off.

Nevinson was one such.

In his Slade days he and a group of his fellow students had terrorised Soho in black jerseys, scarlet mufflers and black caps, outraging passers-by who took them for ‘dirty foreigners’.

But being disapproved of eventually got wearisome.

Nevinson became disillusioned with ‘long hair under the sombrero, and other passéist filth’, and took to dressing like a stockbroker.

Unfortunately this approach turned out to be a minefield.

No sooner had Nevinson reverted to a conventional appearance than other artists, a step

ahead of him, took refuge in the caricature artist image, so as not to look too obviously like revisionist painters.

Ethel Mannin once asked an artist acquaintance why he grew a beard:

He replied that it was partly laziness and partly so that he shouldn’t look like an artist.

‘You can always tell an artist,’ he said, ‘because he looks like a stockbroker,’ or, he glanced at Epstein, ‘a plumber.’

It was perhaps safest, and less studied too, to stick with an unambiguous uniform.

The Bohemian wayside tavern was a welcoming haven for the unconventional dresser; in fact it was a place where not to be eccentric was eccentric, as Mary Colum, a Dublin writer visiting London, found out.

She entered a Bloomsbury pub and happily got chatting to the Bohemian clientele within, only to find herself being asked ‘Do you hunt?’ She had arrived dressed in Irish country clothes – tweeds, a soft felt hat and leather gloves – and had been taken for a lady deer-stalker instead of the free spirit and associate of the great poet Yeats that she saw herself to be: