Among the Bohemians (20 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

He often let favoured boys carry his rifle and sometimes allowed them to have a shot.

If I could have got the rifle into my hands I would have shot him.

Disappointed at not being able to commit a murder to vindicate what I felt to be my honour, I got on my bicycle and rode home.

Was I abnormal, or was there something wrong with my bringing up?

In his autobiography Bunny Garnett concluded that his parents were wrong in giving in to his pleas to be allowed to leave that school.

Looking back, he reproached them for bringing him up to believe that he was somehow superior, and that the rules which applied to most people did not apply to him.

*

The Bohemians’ experiments in child-rearing were at the extreme end of a broader social awareness.

Contemporary educationists, social reformers and novelists shone a new, bright light on to childhood, and illuminated an unfamiliar region.

Samuel Butler’s

The Way of All Flesh

(1903) and Edmund Gosse’s

Father and Son

(1907) were both autobiographies which exposed the misery of the oppressed child, delving deep into individual psychology.

Books like this were ammunition for the generation war and, even where love and sympathy were present, influenced people like the young Arthur Calder-Marshall, who felt driven into Bohemianism:

In retrospect I feel sorry for all parents whose children grew up during the twenties… [

The Way of All Flesh

] exploded like a delayed-action bomb to make innumerable casualties in families unconceived at the time of its composition.

A literary fashion was set… childhoods of misery and misunderstanding were the vogue…

Caught into this war between the artists and the Philistines, we enlisted enthusiastically in the ranks of the artists, swallowing modernism at a gulp and rejecting out of hand the moral and social values which our parents hoped to imbue with us.

Where previously children had been suppressed and largely ignored, children in the twentieth century now took centre stage in a way that magnified their experimental upbringing.

Freud’s case studies, with their emphasis on the early formation of neuroses, and the libertarian experiments in education, both so dear to the hearts of twentieth-century liberals, made of the child a laboratory guinea pig, an object of scrutiny.

Poor Kathleen Hale’s over-nervous husband forbade her to cuddle their children:

He caught onto Freud and all his quirks, and he said to me when my children were born, he said you mustn’t kiss them and you mustn’t hug them, you must never do that with sons, you’ll turn them into Queers…

Each age is a victim of its own theories.

Demographics played their part too, for the turn of the century saw a sharp drop in infant mortality.

Families stopped regarding the breeding process as the provision of ‘spare’ children to take up the slack of natural wastage when the inevitable proportion died from disease.

Instead the individual child was endowed with special, unique, irreplaceable qualities.

But the ideology was new, and the expression of aspirations through one’s children, the determination to see them realize a new kind of society, has left us with not only a legacy of impossible-to-fulfil hopes and dreams, but also the certainty of guilt in our child-parent relationships.

Vanessa Bell’s

‘benign neglect’, the ‘desert of freedom’ referred to by Nicolette Macnamara, Mary Campbell’s unworried irresponsibility, all embodied an attitude quite different from that of the Victorians, with their heedless sentimentality and oppression.

Permissiveness towards children was a statement.

Ethel Mannin believed that complete freedom would result in ‘a new heaven and a new earth for children’:

Pont’s dry observations of the English

character appeared regularly in

Punch

from

1932.

There would be no orthodox schools on this new earth, and no Sunday schools, and no starched nurses with set ideas about things; parents would be ruthlessly segregated, and only allowed to visit their children at the children’s invitation – which means that a very great many parents never would get invited.

The Bohemians may have reacted in extreme ways against the nineteenth century; they were finding their way, but they were nothing if not committed.

They resolved to bring their children up as happy, carefree, creative individuals, and they were determined to spare them the boring, punishing childhoods that so many of them had been forced to endure.

It was Rousseau versus repression.

The predicament is still real today, as the middle classes agonize over the state of education, and chastise themselves mercilessly over the perils of a too strict, or too lenient, or too protective, or too insecure upbringing.

We have never been so obsessed by our children.

But one thing

is certain, nobody ever gets it right.

‘Dear Reader,’ wrote the artist Gwen Raverat in her memoirs, as she pondered this conundrum,

You may take it from me, that however hard you try – or don’t try; whatever you do – or don’t do; for better, for worse; for richer, for poorer; every way and every day:

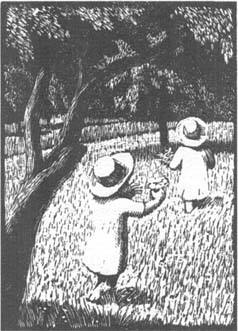

The little pests – Gwen Raverat’s woodcut

‘Children’, 1926.

THE PARENT IS ALWAYS WRONG

So it is no good bothering about it.

When the little pests grow up they will certainly tell you exactly what you did wrong in their case.

But, never mind; they will be just as wrong themselves in their turn.

So take things easily; and above all,

eschew

good intentions

.

4. Dwelling with Beauty

How can one recognise a Bohemian interior? – Does one really need

furniture? – How can one live beautifully and cheaply? – Is innovation

in design compatible with authentic living? – Do things have to match?

– What is the point of wallpaper? – Must furniture be new? –

Is comfort more important than appearance? – Is living the

simple life the answer to poverty?

It is a spring day in 1939, and Theodora Rosling, young, upper class, beautiful and single, is sitting in the Cafe Flore near St Germain des Pres.

But she is not alone for long; drawn into conversation with the distractingly handsome artist sketching at the next table, they are awkward at first, but after a few glasses of wine feel as if they have known each other for years.

Intimacy progresses, the next move is to his place.

They buy food, and champagne, on the way.

Laden with packages they arrive at a little hotel in the heart of the Latin quarter, climb endless flights of stairs, and arrive at last in the artist’s garret.

As Theodora recalled:

The room was an attic of large proportions, with a skylight on one side.

It was cold, the patterned wallpaper was peeling and almost the entire floor space was covered with pieces of screwed-up paper.

They looked like surrealist children’s boats.

The bed hadn’t been made for some time, was rumpled, crumpled and littered with tubes of paint, more pieces of paper, and a beautiful silk dressing gown rolled into a ball.

There were the ashes of a fire in the grate, empty wine bottles, stained glasses, dirty plates, and more tubes of paint on the shelf above the fireplace.

An easel stood in the centre of the room, and on it was a half-finished painting of a large room, empty except for a trestle table.

The walls and floor of the room were painted in very delicate rainbow colours, each hue merging into the next.

The contrast between the painted room and the actual one was startling.

There was a sagging armchair by the fireplace and a hard chair with a cane bottom by the easel.

Stacks of disordered newspapers were in one corner and a small pile of logs.

The other furniture was sparse and battered.

And so the curtain rises on Theodora’s first passion, in which she plays muse to the young artist, against a backdrop of mess, dirt, dilapidation and the

familiar props of the artistic calling.

As the detailed description builds, recalled with all the precision of an indelible memory, the scene becomes increasingly familiar.

No one could fail to recognize the stereotype – we are in the timeless Bohemian heartland: the garret, with its wine glasses, unmade bed and easel.

Here art, in rainbow tints, clearer and brighter than drab reality, is centre stage, and if a room is a portrait of a mind, this one has an explicit statement to make: ‘Look around, I am not bothered by propriety, money or convention; one thing only matters to me, and that is my art.’

The artist’s garret has so transcended fashion and time that it has become one of the most enduring clichés of the age, shorthand for an ideology and an identity, synonymous with both aspiration and despair.

Garrets placed one literally and metaphorically above the world: ‘… the proper writing place is a garret,’ insisted the

fin-de-siède

poet Richard le Gallienne.

‘There is an inspiration in skylights and chimneys.’ By elevating themselves above bourgeois standards of interior decoration, artists declared their transcendence over frills and façades, artifice and ostentation of every kind.

So powerful was this romantic stance vis-à-vis the world of interiors that for artists to survive without comforts, in dust, disorder and want, was to declare their sense of themselves as creative individuals, even as geniuses.

*

It is turn-of-the-century London; the young Arthur Ransome sets out from his suburban home, fired by poetry and thirst for life, practically penniless, but ‘mad to be a Villon’.

He piles his books, clothes and a railway rug on to the back of a grocer’s van, bids goodbye to his relatives, and sets off for Bohemia – which in his case is an unfurnished room in Chelsea at two shillings a week, with a water supply two floors down.

Ransome possesses books, but no furniture.

Undeterred, he wastes no time in setting himself up in his new home with three-and-sixpence worth of wooden packing cases purchased from the nearest grocer:

The boxes were soon arranged into a table and chairs.

Two, placed one above the other on their sides, served for a cupboard.

Three set end to end made an admirable bed.

Indeed my railway rug gave it an air of comfort, even of opulence, spread carefully over the top… I placed a packing-case chair by the open window, and dipped through a volume of poetry…

I was alone in a room of my own, free to live for poetry, for philosophy, for all the things that seemed then to matter more than life itself… Brave dreams flooded my mind…

Ransome was twenty, young enough to find poverty liberating.

His entire Bohemian youth is seen through rose-tinted spectacles, as he himself admitted, and yet one need not doubt that the uncluttering of life provided him with poetic vistas that more well-upholstered members of society may have lacked.

Kathleen Hale too was consumed with nostalgia remembering the early 1920s when she lived in a single large room in Fitzroy Square.

‘It was beautiful, but terribly shabby and dirty,’ she remembered.

Though she too had hardly any money, Kathleen was determined to afford the guinea-a-week rent for this space, but there was almost nothing left over to buy furniture.

She acquired a fourth-hand table, ‘scrubbed until only the hard grain survived, leaving ridges like bleached corduroy’, and got a carpenter to make her a bed for three pounds.

Her boyfriend Frank stole some army blankets for her, but in the winter she was still too cold, and used to layer the blankets with newspaper, which rustled all night, keeping her awake.

Friends gave her a chair, a bucket and a jug.

Early each morning I would blissfully survey my humble possessions.

The spacious bareness around me was heavenly after a childhood spent among heavy furniture, thick carpets and pictures in ponderous gilt frames… The sense of freedom, the lack of responsibility, was quite wonderful…

Such people were living the Bohemian legend.

When Horace Brodsky visited Gaudier-Brzeska’s filthy cold studio in the King’s Road, they became so engrossed in talk that Brodsky missed the last bus to Herne Hill where he lived and, not being able to afford a taxi, was forced to stay the night.

The discomfort of the experience was long recalled.

Gaudier’s only furniture consisted of two benches, a deckchair and an ordinary kitchen chair, and there was no bed.

At three a.m.

Gaudier finally curled up on the deckchair and was asleep in no time, but Brodsky was allocated a work bench studded with projecting pieces of wood to support carvings, and could not sleep a wink.

Then Gaudier woke up, cursed, and started hammering at a piece of stone.

Brodsky abandoned all attempts at rest and came to watch.

All night they talked and Gaudier hammered; at dawn they smelled new bread baking and hurried out to get some breakfast.

Then Brodsky went home, having done his best to clean off the traces of’a crazy night with an irresponsible artist’, adamant that Gaudier’s company was no compensation for discomfort and lack of sleep.