America's Nazi Secret: An Insider's History (18 page)

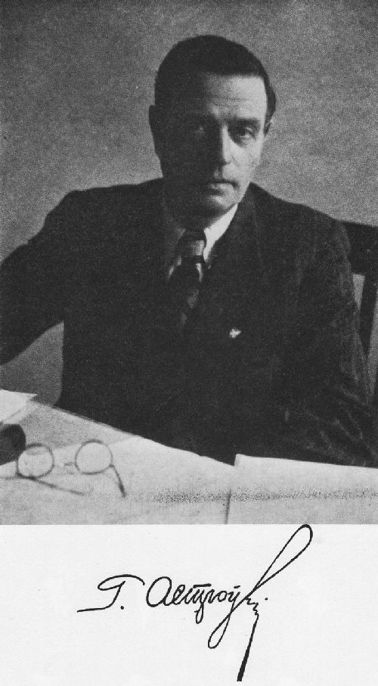

Radoslaw Ostrowsky when he was president of the Byelorussian Central Council in 1944.

Radoslaw Ostrowsky when he was president of the Byelorussian Central Council in 1944.

3

With motorcycle outriders on the alert, a Gestapo staff car drew up in front of SS headquarters in Minsk on December 21, 1943. Ostrowsky was conducted through the barbed-wire barrier and past a heavy guard to meet with General von Gottberg. Security was tight because the Byelorussian capital had become virtually an island in a sea of partisans. The Germans were not even safe within the city itself, for the Soviet underground was active. The nights were filled with explosions and gunfire. Sentries were killed, and their bodies were propped up to be found frozen in a macabre Nazi salute.

Realizing that the Germans needed him if they were to have any hope of recovering their lost support in Byelorussia, Ostrowsky bargained with the SS for an independent Byelorussian state complete with its own army and congress.

46

He was the only person who could unite all the contending factions. He appealed to the Orthodox group in the east because of his role in the abortive Byelorussian government established following the Russian Revolution, and he was acceptable to the Catholic faction in the west because of his association with such old Polish organizations as the Gramada. Ostrowsky also enjoyed the confidence of the Germans. He had played a leading role in establishing German rule in the occupied territories after his return to Byelorussia with the Einsatzgruppen in June 1941. Slighted by Kube, Ostrowsky offered his services to the German army. From Smolensk he moved on to Mogilev and then to other cities on the Russian-Byelorussian border, where he mobilized collaborators, trained police, and directed the elimination of Jews. Now he wished to return to Minsk.

Gottberg was unwilling to go so far as permitting Ostrowsky to establish a full-fledged government. At most, the Byelorussians would be permitted to form a temporary national council with restricted authority. As president, Ostrowsky could choose a cabinet subject to SS approval. The puppet regime would be allowed to organize a centralized Byelorussian home defense corps (BKA) from the 20,000 men in the police battalions already in existence, but it was not to be referred to as a national army and would remain under SS control. If operations against the partisans went well, a national convention might be called in six months.

Ostrowsky insisted that he work directly with Gottberg without the interference of German civilian administrators. He was accustomed to collaborating with the “greens” – the dark green uniformed officers of the Wehrmacht – and he refused to take orders from the remnants of Kube’s inept civilians. Gottberg pointed to his own uniform and assured Ostrowsky that he would still be working for the “greens.” The general wore the gray-green uniform of the SD, the intelligence arm of the SS. If any German interfered with him or his deputies, Ostrowsky was told, Gottberg would order that person sent to a combat unit.

Despite the limitations imposed by Gottberg, the Byelorussians had accomplished what few other Nazi collaborators had been able to do – convince the SS to allow them to organize their own quisling government. This was possible because Byelorussia was the only occupied nation where the SS gained complete political control. Ostrowsky submitted a list of ministers for a Byelorussian Central Council (BCC) to Gottberg for his approval and organized the collaborators in each of the provinces and districts.

47

However, the BCC was infiltrated by Gestapo informants placed by the SS to ensure that the BCC remained loyal to Hitler, as well as by Soviet agents who permeated every level of the German administration in Eastern Europe.

Ostrowsky had only six months to prove that his government was worthy of continued SS backing. Although he had put together a political organization and a military force, he still lacked national recognition or popular acceptance. Tall, eloquent, and magnetic, Ostrowsky immediately launched a propaganda campaign to drum up support for his regime and the battle against the partisans. He was a compelling orator who not only spoke the polished language of the intellectuals, but also appealed to the peasants. He called upon them to fight for “order and peace,” not only for the benefit of the Germans but also for themselves. A Soviet victory would mean the return of communism, and he blamed past atrocities against the peasantry on the “Jew-Bolsheviks” rather than the Nazis. “Forward for the struggle and for the liberation of White Ruthenia with the German people toward victory!” Ostrowsky told a crowd in Baranoviche. “Long live the German Wehrmacht and their Fuhrer, Adolf Hitler!”

48

Warned that one village where he was scheduled to speak was secretly controlled by the partisans, Ostrowsky brushed off the pleas of aides that he avoid the place. Immediately upon his arrival, he went to the village hall and spoke before a crowd that included many suspected partisan sympathizers. He made an emotional plea for the villagers to come over to his side and to fight the Communists, who had done nothing for Byelorussia. Over the next few weeks a significant increase in the number of defections from the partisans was reported in the area.

Ostrowsky persuaded the Germans to reduce their confiscations of crops and livestock to conciliate the peasants and to establish Wehrdorfer, or fortified villages, designed to withstand partisan raids. He also ordered a general conscription to fill the ranks of the BKA. All ex-officers of the Soviet and Polish armies were ordered into service, and draft evasion was punished with death. Some 60,000 men are said to have been conscripted.

49

But the hard core of the BKA was Kushel’s 20,000-man auxiliary police force, which had helped the SS murder the Jews, Poles, and partisans. Recruits wore the Byelorussian white-red-white on their caps and the SS insignia on their collars. Within a few months Ostrowsky managed to convince Gottberg that the nationalist strategy had paid off. The Byelorussian militia was slightly less inclined to terrorize the peasants than the Germans, and they provided information that led to some local successes against the partisans.

50

Gehlen was among those impressed with Ostrowsky’s organizational abilities. Ostrowsky had been mayor of Smolensk at the time Gehlen had his headquarters in the city.

Dimitri Kasmowich, the police chief in the Smolensk region, was one of Ostrowsky’s ablest lieutenants. A strong nationalist, Kasmowich had fled Byelorussia at the time of the Soviet conquest of the Polish-dominated region and had gone to live in Yugoslavia. He returned with the German invaders, and his operations showed what could happen if the Germans allowed the Russians to administer the occupied territories. The forests around Smolensk were dominated by a partisan brigade at the time Kasmowich took control of the police force. With Smolensk as the center, Kasmowich established an expanding ring of defended villages and maintained a motorized reserve ready to meet emergencies. Large areas were swept clean of partisans.

51

As his reward, Ostrowsky received Gottberg’s permission to call a convention of collaborators to solidify the power of the Byelorussian Central Council.

52

The sounds of artillery at the front could be heard in the Minsk opera house as the convention was gaveled to order late in June 1944. The 1,039 “delegates” represented all of the feuding Byelorussian factions, including the western group headed by Mikolai Abramtchik. They had been selected by the SS and screened for loyalty by the Gestapo. Nina Litwinczyk, the Soviet agent who had infiltrated Gestapo headquarters in Minsk, made a careful copy of the list of delegates and forwarded it to Moscow. At first the meeting proceeded according to the scenario prepared by the SS. Ostrowsky made an impassioned speech in support of the Third Reich’s struggle against communism and pledged undying devotion to Hitler’s Germany, which had liberated Byelorussia from the grip of the “Jew-Bolsheviks.”

Then Ostrowsky departed from the SS script. He announced that the work of the BCC was ended and that the convention should pick a new president. The collaborators were as stunned as the SS officers monitoring the convention, but they quickly seized the opportunity. Ostrowsky was immediately chosen president by acclamation. It was a great political coup. He could later claim that he was chosen as president by the “elected” delegates of the Minsk Congress, for in Byelorussian the words “elect” and “select” are the same. In actual fact, only the Germans had had any say in the selection of delegates.

An SS officer immediately went to the podium to put the convention back on track. As a show of submissiveness to German rule, he reminded the collaborators that they had failed to send Hitler a telegram of congratulations on his birthday. A pledge of loyalty was drafted and unanimously approved. The remainder of the convention was tame by comparison, and consisted mostly of resolutions blaming the Jew-Bolshevik conspiracy for all the problems of the nation, from crop failure to labor shortages. In the middle of the Congress the delegates received word that the Red Army had ripped a great gap in the German front. And so the second “great congress” in Byelorussian history ended like its post-World War I predecessor – with the delegates frantically trying to flee the country.

The Nazis had originally planned to make Minsk a fortress city, a last-ditch line of defense along with the other urban strong points, but the partisan revolt and the massive Soviet attack rendered this plan impossible. There was barely time to organize the withdrawal of German administrators, their families, and key collaborators. Ostrowsky insisted, however, that the entire congress and their families must also be evacuated.

53

The SS gave in, and a special train carrying 800 collaborators and their families pulled out of the Minsk railroad station early on the morning of June 28, 1944. Ostrowsky remained behind for another two days to direct the evacuation. It is no small measure of the value the Nazis placed upon their Byelorussian allies that they sacrificed an entire train to transport them at a time when some wounded German soldiers could not be sent home. The SS made a list of those to be evacuated – and nearly every person on it ended up in the United States.

These collaborators were more than cooperative politicians. Although few of them had personally murdered anyone, they were directly responsible for the holocaust in Byelorussia. They were the key organizers of the Nazi intelligence network, a principal tool in the four-year subjugation of Byelorussia. Without these few hundred men there could have been no guides for the Einsatzgruppen, no volunteers to help with the destruction of the Jews. Only with their help could the Germans have recruited the thousands of volunteers needed for crowd control and other measures during the executions. These men ran the ghettos, built the concentration camps, collected the taxes, established the networks of secret informants, and fought the partisans. They were indispensable to Nazi Germany’s control of 10 million Byelorussians.

Before they were evacuated, the collaborators helped the Germans plant explosives beneath every principal factory, office building, warehouse, or granary that had not already been stripped and sent to Germany. When the members of the congress withdrew, they gave the order to scorch the earth behind them. The destruction was appalling. Barely a building was left standing when the Soviet forces recaptured Minsk. The final yardstick of the Nazi occupation was the fact that the civilian population of Byelorussia had decreased 25 percent in three years.

In Berlin, Ostrowsky and his government were warmly received by the Nazis.

54

The ministers were given special ration cards issued only to high-ranking Nazi party members and were assigned to comfortable quarters in the heart of the city. But they must have been shaken by what they saw. Berlin was being bombed around the clock, and the streets were lined with shattered buildings. Bombed-out families lived in the ruins of their homes along with a few rescued possessions. Some of the people were shocked and sullen; others displayed a hysterical merriment often seen in the midst of disaster. Following the raids, a cloud of smoke that reached thousands of feet into the air hung over the burning city, turning day into night.

Kushel’s troops marched a thousand miles to their new home. Most of the recruits conscripted into the BKA remained behind and were given amnesty by the Soviets, but the 20,000 auxiliary policemen who had been absorbed into its ranks were forced to flee. They had earned a special notoriety and knew what their fate would be if they were captured by the Red Army. Along the way these units were absorbed into the 30th Waffen-Grenadier-division der SS-Russiche No. 2.

This infantry division was formed from the remnants of the 29th Waffen-SS Division, which had included Byelorussian and Ukrainian units. Hitler had become suspicious of their loyalty and had ordered them removed from the eastern front, fearing that they would defect to the advancing Red Army. They were transferred to Italy, where in their first encounter with American and Free Polish troops at Cassino a good number of them deserted, as Hitler had predicted. Later, many Byelorussians and Ukrainians were sent to France as members of the 30th Division, where they defected again.