America's Greatest 20th Century Presidents (15 page)

Read America's Greatest 20th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Charles River Editors

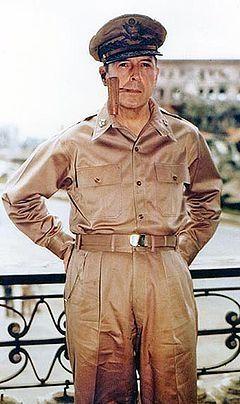

General MacArthur

With this experience in hand, Eisenhower joined General MacArthur in the Philippines in 1935. Having been a thorn in America’s side earlier in the 20

th

century, Eisenhower was there to assist MacArthur in helping the Philippine government develop its own army from scratch, after it had been devastated during World War I. However, the Phillipines proved to be a trying place for Eisenhower. Mamie contracted an illness that nearly killed her there, while the cool Eisenhower clashed with the notoriously feisty MacArthur. Although Eisenhower claimed the falling out between the two was not as bad as has been suggested, his biographers have looked upon this time as a helpful experience that prepared Eisenhower to deal with the equally feisty British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his initially disdainful commander Bernard Montgomery, who would at first openly question Eisenhower’s abilities given his lack of combat service in World War I.

Finally, the interwar period led Eisenhower to be promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1936, for the first time on a permanent basis. In 1939, Eisenhower was relocated back to the United States, where he continued to toil as a staffer in various assignments across the country, but he did have the good fortune of leaving the Phillipines before the start of the Japanese campaign that ousted MacArthur and the Americans from the islands in early 1942.

Thus, as World War II approached, Eisenhower still had never served in active combat even as the nation was preparing for war. Entering the 1940s, Dwight D. Eisenhower was not on many people’s lists of potential American commanders.

Chapter 3: World War II, 1941-1945

Assistant Chief of Staff

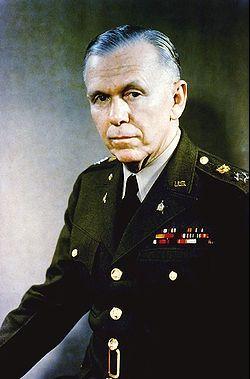

At the onset of World War II, Eisenhower was working alongside General George Marshall as a Assistant Chief of Staff, with Marshall as Chief of Staff, an ironic position given that Marshall would be his main competition for the position of Supreme Allied Commander in Europe a few years later. Eisenhower's promotion to this position came as a result of his earlier commanding of the Louisiana Maneuvers, a set of acts that finally allowed him to enter the radar of leaders in the U.S. Army. The Louisiana Maneuvers were a series of military exercises held in Louisiana that were geared towards preparing the Army for war. Eisenhower led the maneuvers, which were eventually recognized as an exceptionally competent way of training and testing soldiers before sending them into the field.

George Marshall

Now that he had caught the notice of his Chief of Staff, Eisenhower was better positioned to rise rapidly through the ranks of the U.S. Army.

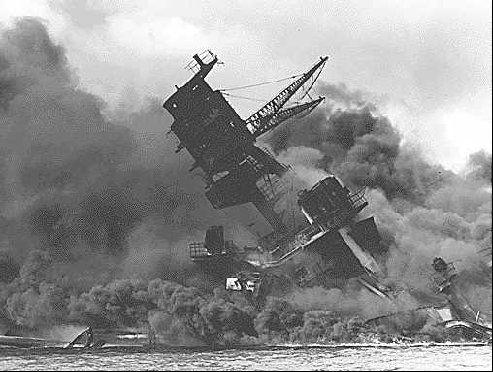

Pearl Harbor

It was literally Eisenhower’s job to plan for war in the event that the United States entered World War II, and there is no doubt that he anticipated the potential for war in 1941. However, so did the Japanese, and both the Japanese and Americans thus made a series of decisions that eventually led to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

When Hitler invaded Russia in 1941, the Soviet Union was facing a mortal threat, and the Japanese, who had fought a war against the Russians less than 50 years earlier, no longer had to worry about the Russian threat on its border. This allowed them to focus their expansion efforts across the Far East and into the South Pacific. At the same time, even while the Japanese expanded across the Pacific during 1941, they were running low on several crucial resources, particularly metal and oil. In response to Japanese aggression in China and other places, the United States had imposed a crippling embargo on Japan, making their shortages even more severe.

With a watchful idea on the expansion of the Japanese Empire across the Pacific, the Roosevelt Administration sought to bolster the Americans’ grip on the Phillipines. As the closest American target to the mainland of Japan, the Phillipines seemed the most obvious target held by American forces for Japanese expansion. With that in mind, President Roosevelt decided to station a majority of the Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Having already devastated China, Japan was looking to Southeast Asia, which was full of Allied targets like the Dutch East Indies, a British possession. Well aware of America’s barely neutral stance and their assistance to the British, the Japanese figured any attack on British targets would bring the U.S. into the war. Thus, the Japanese decided to strike a blow at the United States itself, hoping to buy itself enough time to grab an iron grip in the Pacific while the U.S. rebuilt its crippled fleet.

Japan plotted and trained for an attack on Pearl Harbor for several months leading up to December 7. Believing that a successful attack would buy it the time needed to win the war, the Japanese opted not to attempt to actually invade Hawaii, and their attack ignored the infrastructure on the islands. The Japanese also knew American aircraft carriers would not be at Pearl Harbor but were content to attack the battleships that were stationed there.

Although the United States and its armed forces had prepared for the possibility of an attack, they had not anticipated that it would be at Pearl Harbor, so far away from Japan in the middle of the Pacific. The attacks on December 7, 1941 took American forces completely by surprise, inflicting massive damage to the Pacific fleet and nearly 3,000 American casualties. Several battleships were sunk in the attack. Hours later, the Japanese invaded the Phillipines, where American military leaders had anticipated a surprise attack before Pearl Harbor. Even still, the Japanese quickly overran the Phillipines, forcing General MacArthur to flee to Australia while the unlucky soldiers still stuck on the islands had to endure the Bataan Death March.

At the end of 1941, the Japanese did in fact reign supreme across the Pacific, and it was far from clear that the United States would be able to change the balance of power in the Pacific. Though it was not apparent at the time, Japan’s failure to sink any aircraft carriers proved fatal, as demonstrated at the Battle of Midway the following year. However, the attacks on Pearl Harbor led to a rapid and full scale mobilization of the United States’ economy and war effort overnight. Within months of Pearl Harbor, the United States’ armed forces were helping turn the tide in three different theaters, and Eisenhower would take command in one of them.

Becoming a Commanding General

1942 would be the most momentous year of Eisenhower’s life to date, but it started much like the previous 25 years, with Eisenhower consigned to a staff job conducting military planning far away from the battlefield. Eisenhower shuffled through a handful of administrative jobs in the 1942, including serving on the General Staff in Washington, where he was tasked with creating war plans to topple the Axis in the Pacific and Europe. Later, he was made Deputy Chief in charge of Pacific Defenses under the Chief of War Plans Division, and then he became Chief of the War Plans Division himself.

It would fall on George Marshall to pull Eisenhower out of the staff jobs. After Eisenhower was made Assistant Chief of Staff and put in charge of the new Operations Division (which replaced the War Plans Division), he was once again a subordinate of Chief of Staff General Marshall, who had already taken notice of Eisenhower just recently and now did so again. In May 1942, Eisenhower traveled to London to assess Major General James E. Chaney, who at the time was the commanding general in the European Theater of Operations. When Eisenhower returned to the U.S. a month later and reported back negatively about Chaney, it caught the attention of the military brass, who already knew Eisenhower had a strong reputation for assessing military talent. Thus, that same month, Eisenhower was sent back to London to replace Chaney himself, becoming Commanding General of the European Theater of Operations.

Despite taking command in the European theater, Eisenhower’s first major contribution to the war would take place on a different continent. In e

arly 1942, when President Roosevelt was debating where to put American forces, the Allies, which now included

the Soviet Union by necessity, did not agree on the war strategy. The Germans and British were fighting in North Africa, and the British lobbied for American help in North Africa, where British General Montgomery was fighting the legendary “Desert Fox,” General Erwin Rommel. At the same time, Soviet premier Josef Stalin vehemently argued for the Allies to open up another front in Europe that would help the Soviets, who were facing the brunt of the Nazi war machine in Russia.

The Big 3: Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill, in Tehran, 1943

President Roosevelt ultimately sided with the British and sent American troops to North Africa, so they could help the British oppose Rommel. While this left Russia to handle the Nazis on the European continent singlehandedly, it placed a brand new army to the west of Rommel, ultimately threatening his rear. Though he retained his title as Commanding General in the European Theater, Eisenhower was also chosen to head the American forces in the North African as

Supreme Commander Allied Force of the North African Theater of Operations,

which came to number over 100,000, Eisenhower got his first major experience directing troops in the field. In North Africa, Eisenhower oversaw Operation Torch, with the main objective being to remove the Germans from the North African theater and thus clear the way for a potential invasion of Europe from the south. Although the operation was ultimately successful, Eisenhower suffered fits and starts dealing with battlefield command, often miscommunicating commands and causing confusion. Eisenhower was also not well versed in dealing with military politics, coming under fire for some of his decisions. It was also the first time Eisenhower had to collaborate with General Montgomery, who had won the decisive battle on the continent at El Alamein and bristled about being the subordinate of Eisenhower, who he rightly viewed to be a far less experienced commander.