American Crucifixion (17 page)

Read American Crucifixion Online

Authors: Alex Beam

Attacks of a very different kind quickly followed. In late May 1844, William and Wilson Law charged Joseph with adultery in the Hancock County court at Carthage. They accused the Prophet of living “in an open state of adultery” with Maria Lawrence, between October 1843 and May 1844. William Law not only accused Joseph of fornicating with the young girl, but he also suspected the Prophet had misappropriated the young girl’s substantial, $7,750 inheritance, for which Law was a co-guarantor.

The Laws filed their claim in Carthage to sidestep Nauvoo’s hermetic judicial system. At the same time, William Law sent $2,000 to a publisher in Quincy, Illinois, to purchase a “5 d press with a 25” x 38” platen,” and printing supplies. The Laws and their confederates were going into the newspaper business.

*Scholars disagree on the number of wives Joseph had. Todd Compton estimates thirty-three; George D. Smith says thirty-eight; Fawn Brodie lists forty-eight; D. Michael Quinn counts forty-six.

* For decades, some Mormon apologists denied polygamy’s existence, arguing: why were there no children born of plural marriage? In 1880, Elder Ebenezer Robinson quoted Hyrum Smith as saying that if a plural wife “should have an off spring, give out word that she had a husband who had gone on a foreign mission.” Robinson further recollected that “there was a place, a few miles out of Nauvoo, in Illinois, where females were sent” to bear children away from the scrutiny of their friends and neighbors. In 1905, Mary Rollins told a Salt Lake City audience that three of Joseph’s children reached adulthood, their identities concealed by “different names.”

PART TWO

“Oh! Illinois! thy soil has drank the blood / Of Prophets martyr’d for the truth of God.”

6

“THE PERVERSION OF SACRED THINGS”

This day the Nauvoo Expositor goes forth to the world, rich with facts, such expositions as make the guilty tremble and rage. . . .

—William Law’s diary, Friday, June 7, 1844

IN THIS HIGH-STAKES POKER GAME, NONE OF THE PLAYERS WERE bothering to hide their hands. Not only had the Fosters and Laws filed separate complaints, one for adultery and the other for “false swearing,” against Joseph in state court at Carthage, they also announced their plans to publish a new, independent newspaper outside the ambit of Smith’s benevolent dictatorship. The city’s two existing newspapers, the

Nauvoo Neighbor

and the

Times and Seasons

, were organs of the ruling theocracy, both edited by Apostle John Taylor. The new entrant would be something else entirely. “The paper I think we will call the Nauvoo Expositor,” dissident Francis Higbee explained to the newspaper editor, Thomas Gregg,

Nauvoo Neighbor

and the

Times and Seasons

, were organs of the ruling theocracy, both edited by Apostle John Taylor. The new entrant would be something else entirely. “The paper I think we will call the Nauvoo Expositor,” dissident Francis Higbee explained to the newspaper editor, Thomas Gregg,

for it will be fraught with Joe’s peculiar and particular mode of Legislation; and a dissertation upon his

delectable

plan of Government; and above all, it shall be the organ through which we will herald his

Mormon

ribaldry. It shall also contain a full and complete exposé of his

Mormon seraglio

, or

Nauvoo Harem

, and his unparalleled and unheard of attempts of seduction.

The editorial team assembling the

Expositor

inside the Laws’ printing office on Mulholland Street, just a few hundred feet from the Nauvoo Temple site, was a motley crew. William Law supplied the capital. He, the Higbees, and the Fosters supplied the vitriol. The nominal editor, the Gentile lawyer Sylvester Emmons, later admitted that “none of us knew anything about journalism. I had written a few letters that were published in the New York

Herald

, so in organizing the forces, I was elected as editor.” Emmons claimed to be a member of a Nauvoo clique, “a Gentile club, smarting under grievances unendurable, [that] sympathized with the seceders.” Publishing the

Expositor

was “a hazardous enterprise,” he judiciously noted, “and the result might have been seen, if the seceders had exercised a fair share of caution.”

Expositor

inside the Laws’ printing office on Mulholland Street, just a few hundred feet from the Nauvoo Temple site, was a motley crew. William Law supplied the capital. He, the Higbees, and the Fosters supplied the vitriol. The nominal editor, the Gentile lawyer Sylvester Emmons, later admitted that “none of us knew anything about journalism. I had written a few letters that were published in the New York

Herald

, so in organizing the forces, I was elected as editor.” Emmons claimed to be a member of a Nauvoo clique, “a Gentile club, smarting under grievances unendurable, [that] sympathized with the seceders.” Publishing the

Expositor

was “a hazardous enterprise,” he judiciously noted, “and the result might have been seen, if the seceders had exercised a fair share of caution.”

But theirs was not a cautious enterprise. A couple of weeks before their first issue, the

Expositor

’s owners distributed a flyer detailing what exactly they intended to expose. Nominally devoted to “the general diffusion of useful knowledge,” the newspaper’s prospectus struck directly at the heart of Nauvoo’s one-man rule. The Laws and their colleagues demanded the repeal of the Nauvoo Charter, which arrogated so many powers to the man they now regarded as a fallen prophet. They vowed to print the “FACTS AS THEY REALLY EXIST IN THE CITY OF NAUVOO

fearless of whose particular case the facts may apply.

” The dissidents also advocated “unmitigated DISOBEDIENCE TO POLITICAL REVELATION” made by the city’s “SELF-CONSTITUTED MONARCH.”

Expositor

’s owners distributed a flyer detailing what exactly they intended to expose. Nominally devoted to “the general diffusion of useful knowledge,” the newspaper’s prospectus struck directly at the heart of Nauvoo’s one-man rule. The Laws and their colleagues demanded the repeal of the Nauvoo Charter, which arrogated so many powers to the man they now regarded as a fallen prophet. They vowed to print the “FACTS AS THEY REALLY EXIST IN THE CITY OF NAUVOO

fearless of whose particular case the facts may apply.

” The dissidents also advocated “unmitigated DISOBEDIENCE TO POLITICAL REVELATION” made by the city’s “SELF-CONSTITUTED MONARCH.”

Smith had faced worse, much worse, in the pages of far more august newspapers than a putative journal edited by a tiny claque of disaffected Saints. The paper’s prospectus didn’t overtly mention polygamy, although its promise to censure “gross moral imperfections” hinted at things to come. Joseph could still allow himself to hope that the prurient details of his inner circle’s plural marriages would remain secret. But the allusion to a “self-constituted monarch” gave pause. Was it possible that the Laws and Fosters planned to expose the Council of Fifty, whose members had been sworn to strictest secrecy? How would the world react to discovering that a presidential candidate had appointed himself “King of the Kingdom of God and His Laws with the Keys and powers thereof”?

Even without seeing the paper, Joseph sued for peace. He sent his trusted aide Dimick Huntington to treat with Robert Foster. But the refractory doctor sent Huntington packing, with a fiery response to Smith: “You have trampled upon everything we held dear and sacred . . . we set hell at defiance, and all her agents.” Uncowed, Joseph then dispatched his first counselor, Sidney Rigdon, to William Law’s house, offering terms: If the Laws and the Fosters would stand down, the Council of Fifty would reinstate them into the church and restore their ecclesiastical status. William Law would be second counselor, number three in the hierarchy again, and his wife could also rejoin the Saints. Law offered a counterproposal. We won’t publish our paper, he said, if Joseph would publicly apologize for teaching and practicing “the doctrine of the plurality of wives.” Law also wanted Joseph to acknowledge that the whole polygamy scheme was “from Hell.”

That was not a deal Rigdon could make. Soon afterward, the first thousand copies of the

Expositor

rolled off the printing press.

Expositor

rolled off the printing press.

Editor Emmons was away from Nauvoo on publication day, June 6, 1844; he had business in Springfield. He later claimed that “I had prepared some manuscript—a salutatory and some other articles—in which the case was drawn rather mild.” The paper that hit the streets in his absence contained considerably more ginger. “During my absence,” Emmons said, “Charley Foster and some others took the privilege of inserting articles that reflected rather severely upon the character and Christian conduct of the prophet. . . . Charges of a heinous nature were preferred against him, and to have such charges published was a fearful ordeal for him.”

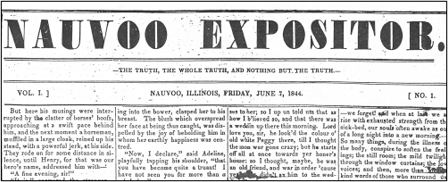

The front page masthead of the first and only issue of the

Nauvoo Expositor

Nauvoo Expositor

The four-page, six-column broadsheet bore the trappings of any midcentury, small-town American newspaper. The front page featured a simple poem (“The Last Man”), and a short, sentimental story. The

Expositor

had a wedding announcement, a few humorous snippets, and ads—one for a penmanship course, another placed by the Law brothers themselves, offering to mill grain “toll free” for Saints too poor to pay their fees. (This was quite politic of them, given that Joseph had publicly denounced their real estate profiteering.) The paper reprinted brief overseas dispatches from Russia and the “papal dominions,” as well as an account of Philadelphia’s anti-Catholic riots.

Expositor

had a wedding announcement, a few humorous snippets, and ads—one for a penmanship course, another placed by the Law brothers themselves, offering to mill grain “toll free” for Saints too poor to pay their fees. (This was quite politic of them, given that Joseph had publicly denounced their real estate profiteering.) The paper reprinted brief overseas dispatches from Russia and the “papal dominions,” as well as an account of Philadelphia’s anti-Catholic riots.

A woman named Lucinda Sagers placed this notice:

WHEREAS my husband, the Rt. Rev. W. H. Harrison Sagers, Esq., has left my bed and board without cause or provocation, this is to notify the public not to harbor or trust him on my account, as I will pay no debts of his contracting. More anon.

This questionable character was the aforementioned Harrison Sagers, whom Joseph had allowed to secretly marry his young sister-in-law, Phoebe Madison.

But no one bought the

Expositor

for its account of Jewish persecutions in Saint Petersburg, or its article about nativist riots back East. The Laws and the Fosters appreciated the ferocious power of a well-edited newspaper, and they devoted most of the column space to attacking Joseph Smith and his comrades.

Expositor

for its account of Jewish persecutions in Saint Petersburg, or its article about nativist riots back East. The Laws and the Fosters appreciated the ferocious power of a well-edited newspaper, and they devoted most of the column space to attacking Joseph Smith and his comrades.

To do that, they needed to lay a little groundwork. First and foremost, the editors insisted that they were faithful Mormons: “We all verily believe, and many of us know of a surety, that the religion of the Latter Day Saints, as original taught by Joseph Smith . . . is verily true, and that the pure principles set forth in those books, are the immutable and eternal principles of Heaven.” One hears an echo of the Declaration of Independence in their claim to be “striking this blow at tyranny and oppression . . . though our lives be the forfeiture.”

The editors’ first concern was polygamy, “the perversion of sacred things.” By way of condemning “the vicious principles of Joseph Smith, and those who practice the same abominations and whoredoms,” the dissidents printed a long, baroque, fictionalized account of the attempted seduction of an unnamed young immigrant girl from England. The innocent girl arrives in Nauvoo, where Joseph’s panders promptly pounce on her. They inform her that “God has great mysteries in store for those who love the lord, and cling to brother Joseph.” Next, the girl is

requested to meet brother Joseph, or some of the Twelve, at some insulated point . . . or at some room, which bears upon its front—Positively NO Admittance. The harmless, inoffensive and unsuspecting creatures are so devoted to the Prophet and the cause of Jesus Christ that they do not dream of the deep laid and fatal scheme which prostrates happiness, and renders death itself desirable.

Other books

The Random Acts of Cupid (Christian Romance) by Tru, Amanda

Where Love Grows by Jerry S. Eicher

We Are Here by Cat Thao Nguyen

The Long Night by Dean Wesley Smith, Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Dust by Hugh Howey

The Boss Vol. 4 (The Boss #4) by Cari Quinn, Taryn Elliott

Zeina by Nawal el Saadawi

Big Girls Do It Better by Jasinda Wilder

Anno Zombus Year 1 (Book 4): April by Rowlands, Dave