America I AM Pass It Down Cookbook (24 page)

Cut corn from the cob into a mixing bowl by slicing from the top of the ear downward. Don’t go too close to the cob—cut only half of the kernel. Scrape the rest off. This gives a better texture the pudding.

Sprinkle in the sugar and salt, stir well. Mix the beaten eggs and milk together, and pour the mixture into the corn. Add the melted butter. Mix thoroughly and spoon the mixture in to a well-buttered casserole.

Sprinkle over with nutmeg. Set the casserole into a pan of hot water and set this into a preheated 350° F oven for 35 to 40 minutes or until set. Test by inserting a clean knife into the center of the pudding. If it comes out clean it’s done.

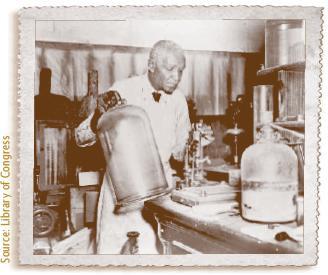

Dr. George Washington Carver

Dr. George Washington Carver, M.S. AGR., D.Sc., Director, Experiment Station, Tuskegee Institute, is most known for his work with peanuts, but his work as a horticulturist extended to making the most of poor soil for sustenance crops that could be put to both edible and non-edible use. These included not just the peanut, but soybeans, cowpeas, and sweet potatoes. Dr. Carver’s sweet potato wisdom, originally shared in the 1920s is still informative and inspiring today.

“There are but few if any of our staple farm crops receiving more attention than the sweet potato, and indeed rightfully so—the splendid service it rendered during the great World War in the saving of wheat flour, will not soon be forgotten. The 118 different and attractive products (to date) made from it, are sufficient to convince the most skeptical that we are just beginning to discover the real value and marvelous possibilities of this splendid vegetable.

Here in the South, there are but few if any farm crops that can be depended upon one year with another for satisfactory yields, as is true of the sweet potato. It is also true that most of our southern soils produce potatoes superior in quality, attractive in appearance and satisfactory in yields, as any other section of the country.”

“As a food for human consumption, the sweet potato has been, and always will be, held in very high esteem and its popularity will increase in this direction as we learn more about its many possibilities.

There is an idea prevalent that anybody can cook sweet potatoes. This is a very great mistake, and the many, many dishes of ill-cooked potatoes that are placed before me as I travel over the South prompt me to believe that these recipes will be of value (many of which I have copied verbatim from Bulletin No. 129, U. S. Department of Agriculture). The above bulletin so aptly adds the following:

The delicate flavor of a sweet potato is lost if it is not cooked properly. Steaming develops and preserves the flavor better than boiling, and baking better than steaming. A sweet potato cooked quickly is not well cooked. Time is an essential element. Twenty minutes may serve to bake a sweet potato so that a hungry man can eat it, but if the flavor is an object, it should be kept in the oven for an hour.”

Dr. Carver’s Sweet Potato Croquettes

Tuskegee, Alabama

SERVES 4

2 cups mashed, boiled, steamed, or baked sweet potatoes

2 egg yolks

1 whole egg

1½–2 cups fresh breadcrumbs

lard or oil

salt to taste

Put sweet potatoes and beaten yolks of two eggs in a pot, and season to taste.

Stir over medium fire until the mixture pulls away from the sides of the pot.

Let sit covered in refrigerator for 1 hour.

When cold form into small croquettes. Roll potato balls in egg and breadcrumbs, and fry in hot oil to amber color.

Serve.

Sweet Potatoes Baked With Apples

Tuskegee, Alabama

SERVES 4

4 medium-size sweet potatoes

4 medium-size apples

1½ cups sugar

1½ cups butter cut into slices

¾ pint hot water

salt to taste

Wash, peel, and cut the potatoes in slices about ¼ of an inch thick.

Pare and slice the apples in the same way.

Put potatoes and apples in baking dish in alternate layers.

Sprinkle sugar and butter over the top, along with hot water.

Bake slowly at 350° F for one hour.

Serve steaming hot.

A Taste for the Past

BY GUY - OREIDO WESTON

Guy-Oreido Weston is an HIV program consultant living in the Washington DC area. His passion for researching the remarkable history of his ancestors of Timbuctoo has culminated in a lifelong project and various writings.

E

ven as a child,

my favorite people were the matriarchs in my life: my mother, mother’s friends, grandmothers, grandmothers’ sisters, and their female cousins. Among these women, the person who left me the most lasting legacy was Lillian Giles Gardner, my maternal grandmother’s first cousin. Lillian was an elegant, beautiful, and youthful woman at every age. A retired jazz vocalist, she was progressive and open-minded in an era when the norm was respecting the status quo. While most of the Giles family was Methodist or Baptist, Lillian was Episcopalian. I think my siblings and I looked up to Lillian because she was “different.” As teenagers, she made us feel comfortable discussing things we felt we couldn’t discuss with our parents.

Among all of the cooking women in the Giles family, in my mind, Lillian was the most gifted. In addition to the “down home” recipes of corn pudding, candied sweet potatoes, fresh collard greens, succotash, stewed tomatoes from scratch, and a variety of cakes and deep dish pies, Lillian could make soufflés and various gourmet recipes. So if I needed pointers on cooking something, Lillian was right up there with my mother as a go-to. As a young adult living on my own for the first time, I began calling Lillian more often. One day, when I needed a recipe for a distinctive dessert, she gave me an applesauce cake recipe that still gets rave reviews whenever I make it. Eventually, she gave me a 1950s-era Betty Crocker cookbook that continues to be my primary cooking reference to this day.

But the most enduring legacy was not the cookbook. Lillian was also the guardian of the old, rural, family homestead. She was the first family member to tell me and my siblings about it when I was 13. No one had lived there since the 1930s, and the house was gone long before I was born. Fortunately, various relatives had kept up the taxes for more than 60 years, sometimes not laying eyes on it for a decade or more. I knew my great-grandmother was born there in 1902, but I had no idea that she was the fourth generation to live at the site.

The area where our homestead was is called Timbuctoo, located in Westampton Township in southern New Jersey. Although most county residents may have never heard of it, it appears on area maps under that name to this day. It was founded by freed blacks and runaway slaves around 1820 with the support of local Quakers.

At its peak in the mid-1800s, Timbuctoo had more than 125 residents, a school, an AME Zion Church, and a cemetery. It was also a stop on the Underground Railroad. Today, only the cemetery remains, which contains the graves of black Civil War veterans.

When I saw Timbuctoo for the first time as a teenager, it was anything but a historic site. The grass on our ½5-acre lot was waist high. The adjacent lot had a dilapidated old house with an abandoned 1962 Ford Galaxy next to it. That was around 1975. Over the next few years, I would ride by that lot from time to time and just stare into the pasture and wonder what it must have been like to grow up there in the early 20th century.

One day in the mid-1980s, my mother and I went to visit Lillian. She had decided that she wanted to transfer the land to a younger generation, and she would begin by sharing various documents related to the property. She pulled out a rather non-descript manila envelope that contained the original 1829 deed from when my great, great, great, great grandfather bought his first parcel for $30. There was also a deed for an adjacent parcel purchased in 1831 for $8.50, a will from 1842, mortgage documents from 1845, and various receipts for mortgage payments and taxes through the 1930s.