Amazing Grace (14 page)

Authors: Nancy Allen

“And your pumpkin blossoms helped my bees make some mighty fine honey,” Grandma said. “Especially Polly Nate.”

We looked at each other and giggled as we remembered Johnny thinking “pollinate” was a person.

Grandma pulled on a long-sleeved shirt, a pair of long pants under her dress and some kind of hood over her head that had netting. She called it a veil. That woman looked like a Halloween spook and could have won first prize for her costume.

Grandma walked into her garden shed and came out carrying a square metal box with leather pleats like an accordion.

“What's that?” I asked.

“A smoker,” Grandma answered. “Hot coals go in the metal part, the burner. When I squeeze the bellow,” she pointed to the leather pleats, “smoke blows out of this hole.” She turned the smoker to the side so I could see each part.

I stared at the strange-looking contraption and asked, “Why do you need smoke?”

“Smoke quiets the bees, and I can extract the honey without getting stung,” Grandma answered. “You stay here if you want to watch. I'm going into the kitchen to get the hot wood coals.” She tugged on a pair of gloves as she walked away.

I watched Grandma hike to the beehives. In a few minutes, she shuffled back, lugging a bucket full of honey. After she poured the honey into canning jars and sealed each with a lid and a screw-on cap, Johnny and I grabbed the bucket. We swiped warm biscuits along the inside to sop up the leftover syrupy treat.

When Mom came home from working in the apple orchard, I told her about my day. Together, we counted my money one more time: $17.25 and a quarter for Spot.

“I'm so proud of my amazing Grace,” Mom said. “I'll talk with Mr. Wilson about finding another bicycle for you.”

I had lots of news for Daddy, so I fired off a letter.

Dear Daddy,

Grandma said my pumpkins werebodayshusbodacious. I watered and hoed them and pulled weeds all summer. Those orange balls started out marble-size and some ended up as big as a washtub. Really. The big green vines grew like weeds. That's what Grandma says I'm doing, too, growing like a weed.

My pumpkins sold, right down to the last one. I saved two for Johnny and me and two for my friend Vickie. She's the girl in my class who gave me her pumpkin seeds. Vickie is going to carve jack-o'-lanterns out of the pumpkins, and her mom is going to make pumpkin pies. Mr. Wick took threeâone for him, one for Holly the Collie and one for his mule, Moonglow, the future Kentucky Derby winner. He paid me for the pumpkins and even gave Spot a quarter, which he spent on a treat from Mr. Wilson's store. Spot said it was bodacious too. Johnny and I are saving our pumpkins to carve into jack-o'-lanterns, and Grandma is going to make pies.

Some of the pumpkins were so big Grandma had to help me carry them out of the patch. Johnny wanted to help. First thing, he dropped a pumpkin and broke it. Grandma said that was good, because she would use it to make a pie. Grandma's pie was spicy, sweet and scrumptious. Johnny said the whole pie should be his since Grandma wouldn't have baked it if he hadn't dropped the pumpkin. When I asked for a piece of pie, that boy handed me a carrot. I told him if I didn't get any pie, he owed me for the pumpkin he broke, that I'd take one of his toys for pay. He dropped the carrot and handed over a slice of the sweet stuff.

I wish you could have seen my cantaloupes lope. The scampering vines scooted all over my garden, but they sprouted mouthwatering melons, so we're not complaining.

Mr. Wilson has had trouble finding a bicycle to fix up. He promised I could have the next one. Mom says I have enough money to buy it.

I saw a poster “Even a little can help a lotâNow” urging us to buy savings bond stamps. And I did with some of my pumpkin money. My book is growing with saving stamps. When the book is full, I'll buy a victory bond. Grandma said I was helping the soldiers and helping myself at the same time.

Mrs. Howard, my new teacher, told me I'm the best reader in seventh grade. I've been reading “Rabbit Hill.” Johnny has learned to read too. His new teacher is Mrs. Eversole. Johnny knows the alphabet forward, but he can't say it backward the way I can.

We still listen to the wireless every evening. The newsman said some troops had moved into Germany and that the end of the war is closer. We cheered when we heard those words.

Please hurry home.

I love you,

Gracie Girl

P.S. Spot howls at the moon until I raise my window and tell him goodnight. Johnny says my sweet mutt is chasing away ghosts and goblins. I think he's practicing dog talk. Spot needs the practice so he'll be able to talk with his pal Abby when we move back to Hazard.

On Saturday, I mailed my letter to Daddy. Saturday was a sad day. First, Farmer Smith said he couldn't pay Mom. This had been a bad year for apples. Second, Mom couldn't pay the bill at Mr. Wilson's store. This year has not been so great for us either.

Chapter 21

Tough Times

October rolled in with no letter from Daddyânot one word since June. Daddy had been faithful about writing to us until the Normandy invasion.

“No news is good news,” Mom said.

Scary thoughts filled my mind. I couldn't help but wonder if I would ever hug my daddy again, dance with him or listen to one of his goodnight stories. My thoughts floated clear across the ocean. I checked the mapâthe Atlantic Ocean.

We never talked much about why Daddy's letters stopped coming in the mail, but we clung to all the news reports on the wireless. Music, we didn't listen to it. Singing and dancing were not the same with Daddy gone. Instead, we listened to a different kind of musicâGrandma's humming. For the last few days, Grandma had been humming all the time. I don't know if she hummed a real song or not. She hummed

um hummmm hum

over and over, real low like the humming was meant just for her.

One afternoon, Mom said, “You and Johnny, go clean your room.” As I walked to our bedroom, I heard Grandma and Mom talking quietly. I walked real slow so I wouldn't miss too much.

“I have to find a job soon,” Mom said in a hushed voice. “Farmer Smith said he would pay me when he could, but that could be next year.”

“Farmer Smith should have borrowed my bees to pollinate his apple crop,” Grandma said. “That man wouldn't listen to reason. He claimed blight caused his apples to be puny little knobs of nothing. Blight had nothing to do with it.”

“This was his first year owning the orchard,” Mom said. “He's already said he wants to buy some bees for next year's crop, but that won't help me now. I need to pay Mr. Wilson the bill for groceries that I've run up at his store.”

I glanced back. Mom looked sad, and sad didn't look good on Mom. All my life I was used to seeing Mom happyâuntil Daddy left.

I eased out the back door to talk with Spot. Somehow, I always felt better after talking with that clever mutt. Spot bounded over. He stood, and I sat on a big rock.

“We didn't get a letter from Daddy again today. I thought you'd want to know. That's over four months. Mrs. Jonesâyou know Mrs. Jones, Spot, she's the woman who wears the big hats that you bark at.” Spot looked at me and blinked his eyes. He reminded me of Johnny trying to act so innocent. “Anyway, Mrs. Jones brought our mail to us today, and we didn't have a letter from Daddy.”

Spot stared; he didn't move a muscle, not even a blink.

“I don't know what could be wrong.” Any reason I came up with was so worrisome the words refused to come. That sweet mutt continued to stare at me. He didn't have anything to say either. I guess Spot was as worried as I was. After a few minutes, I kissed him on his head and told him goodnight.

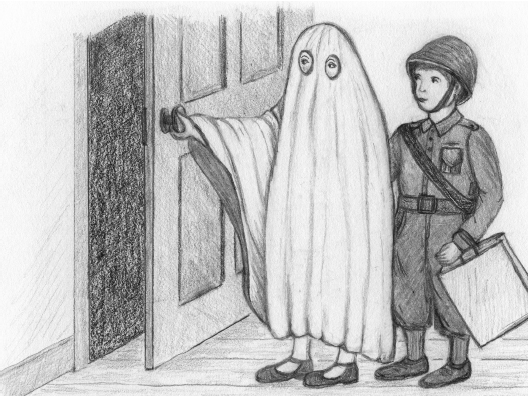

The next evening, Johnny and I dressed up for trick-or-treating. An old sheet with two holes for the eyes covered me. Johnny said he wanted to be like Dad, so Mom dressed him as a soldier.

Johnny bounded out the door and down the steps with a paper sack in his hand, ready to collect goodies and fill his treat bag. I snuck out the kitchen door and across the yard to hide behind the big oak tree. Johnny turned in a circle looking for me. I sneaked up behind him and moaned real low. He turned around and saw me and streaked up the steps so fast he missed the top two, yelling, “Haints! Haints are on the prowl in the front yard!” He darted into the house and slammed the door.

I slipped through the kitchen door and walked into Grandma's parlor.

“There's no haint in the front yard,” Mom said.

“Oh yes there is,” Johnny corrected her. “I saw one.”

“There's the ghost you saw,” Mom said. “Your sister.”

Johnny narrowed his eyes and looked at me. “Uh-uh,” he said. “She's not the same haint I saw out in the yard.”

“Come on, scaredy cat,” I joked as I opened the door. “Let's go trick-or-treating.”

“I'm not going,” Johnny said. He crossed his arms over his chest, a sure sign that a stubborn spell had come over him.

“Let's go, Johnny,” Mom said. “I'll be with you.”

“Uh-uh,” that boy mumbled.

“I guess I'll be the only one to get candy or cake,” I told him.

“I'm ready,” he said. Candy was the magic word with him. He stuck his head out the door and eyed the front yard. He mouthed, “No ghosts,” to Mom.

Mom mouthed, “No ghosts,” back to Johnny, and off we went to our school for a Halloween costume party. Sugar and chocolate were rationed, so we didn't get a lot of candy, but we did get some bubble gum and popcorn balls.

The next afternoon when I got home from school, Mom walked into our bedroom. I showed her Rubble Trouble's stuff scattered everywhere on his side of the room and on my side. Worry carved lines on Mom's face, lines I hadn't seen before. Instead of complaining, I said, “Where are you going to work now, Mom?”

“I don't know,” she answered. “I'll find work somewhere. Maybe at the Clayton Lambert Munitions Factory. They make shell casings for the navy. Or maybe a store in town.” Then Mom smiled. “I have good news. Mr. Wilson found a bicycle for you, and he painted it red. You've got time to go buy it before the store closes if you hurry.”

A bicycle! That was all I needed to hear. I emptied my piggy bank into my pink pocketbook and skedaddled out of the house and down to the store. Spot trotted along beside me.

The red bicycle was shiny and slick, standing in the middle of the store, strutting its stuff. I got all jumpy inside, and when I touched the handlebars, my knees wilted. Mine. All mine. The bicycle was a beauty, prettier even than the first red one I had my heart set on. With a hop, I eased onto the seat and moved the handlebars, pretending to ride.

I had the jitters and the dumps at the same time. The bicycle was perfect, but as I looked at it, I saw Mom's sad face in my mind. I had enough money to buy it, but I wondered: Was this bicycle really what I wanted? I asked myself that question again and again.

The clock on the wall rang loudly. Time was running out. The store closed at six o'clock. I had to make up my mind, fast.

Mr. Wilson walked over. “Well, Grace, what do you think of this fine piece of machinery? I saved it for you.”

I didn't know what to say to Mr. Wilson. I knew he had worked hard to paint the bicycle and make it all spiffy, but I had figured out what I wanted even more than the shiny red beauty. I wanted to make Mom feel better, so I used my pumpkin money to help pay the grocery bill.

Mom, Grandma and Johnny were waiting on the front porch for me when I walked back home with Spot.

“Where's the bicycle?” Johnny asked.

After I explained why I didn't buy the bicycle, Mom turned and walked into the house. Never said a word. Grandma gathered up her knitting and rocked and hummed and mumbled something about gumption.

Chapter 22

Surprises

By the middle of November, we still hadn't received a letter from Daddy. Five whole months had gone by. More and more injured soldiers returned home. Mom talked with many of them. Grandma did too. After each conversation, Grandma said, “No news is good news.” Mom agreed.

Each day when I got home from school, I asked if we had gotten a letter.

Mom's answer was always the same: “Not today; maybe tomorrow.”

Sadness sneaked in and staked a claim with me. I walked out back to talk with Spot. “We should have heard from Daddy by now,” I said.

Spot whined. That's dog talk for telling me he agreed.

One Saturday morning, I crawled out of bed and found Johnny's stuffâclothes, toys and scraps of foodâscattered all over the floor, all over the beds, all over our room. I gathered up all his stuff and piled it on top of his bed. I found a ball of Grandma's red yarn and strung a line across the middle of the floor.

“Johnny, come here!” I called out plenty loud enough for him to hear.

He never came. I guess he thought I wanted him to clean up his mess. I did, but even more, I wanted to show him his half of the room.