Almost President (50 page)

Authors: Scott Farris

Less than two weeks after the election, Dole went on the satirical television program

Saturday Night Live

, to spoof his loss and his alleged tendency to speak of himself in the third person, complaining, “That's not something Bob Dole does. It's not something Bob Dole has ever done, and it's not something Bob Dole will ever do!”

He wrote a memoir of his war experience and put together two books on political humor:

Great Presidential Wit: (Wish I Was in the Book)

and

Great Political Wit: Laughing (Almost) All the Way to the White House.

They sold well, and Dole's second wife, Elizabeth, had a good job running the American Red Cross. But Dole never forgot the hardscrabble times of his youth, and perhaps he succumbed to the envy that many politicians feel as they solicit contributions from the rich and peek into their world while still earning a public servant's salary. So, Dole became a spokesperson for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, and then he spoofed that spokesmanship in an ad for Pepsi in which the then seventy-eight-year-old politician feigned lust for teen pop starlet Britney Spears. A lot of people thought it was undignified, but if Bob Dole hadn't earned the right to make a few bucks making people guffaw, who had?

Richard Ben Cramer,

What It Takes

(Vintage Books, New York, 1993).

Robert J. Dole,

One Soldier's Story: A Memoir

(HarperCollins, New York, 2005).

Addendum

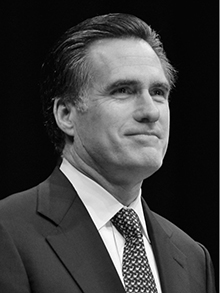

MITT ROMNEY

2012

I have “concepts” that I believe.

On Election Day 2012, Mitt Romney made it known that he had not bothered to write a presidential concession speech, only a victory speech. So when Barack Obama won convincingly, and with the result known relatively early in the evening, Romney, whom aides described as “shell shocked,” had little time to prepare remarks for what would be one of the most important speeches of his public life.

As noted in chapter 1, a concession speech is the last opportunity for a losing presidential candidate to have the full attention of the nation. The defeated candidate typically uses the platform to sum up the meaning of his campaign and define his political legacy. Romney spent most of his address thanking his family and staff for their hard work. His concession came across as perfunctoryânot ungracious, but hardly among the best of a genre that can inspire either newfound admiration or even buyer's remorse among the listening audience.

Whether Romney had truly failed to prepare a concession out of bravado or superstition, his speech was more than a missed opportunity; absent a declaration of his campaign's underlying meaning, it fed a perception, particularly within Republican ranks, that Romney's campaign had been about nothing.

This perceived emptiness was particularly bitter for conservatives, who had hopes that 2012 would be a consequential election fought along sharply ideological lines. Republicans considered Obama's initial election in 2008 a fluke, an instance where the nation was temporarily mesmerized by the historic significance of electing the first African-American president. Instead, Obama earned a second term by a comfortable 51â47 percent margin in the popular vote and with 332 electoral votes to Romney's 206.

1

Â

History will determine just how consequential the 2012 results turn out to be (and Barry Goldwater and George McGovern stand as reminders that judgment should not come too quickly), but Romney's candidacy had historic elements. Romney, after all, was the first member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (more popularly known as “Mormonism”) to be nominated for president. Given that a significant number of Americans do not consider Mormonism a Christian religionâand some consider it a cultâthe 2012 Republican campaign was a milestone in the American tradition of religious pluralism and tolerance.

2

Â

Romney, who had risen to the rank of bishop in the lay ministry that is a feature of Mormonism, had feared he might fall victim to the bigotry Al Smith had faced in 1928 as the first Roman Catholic nominee for president. It didn't happen. Romney's religion was little discussed during the campaign, and post-election surveys indicated religion had not been a factor in shaping the election results. Romney's candidacy was made even more remarkable when he chose as his running mate a Roman Catholic, Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan, meaning Romney-Ryan was the first presidential ticket in American history without a Protestant member.

3

Romney's candidacy, while religiously historic, also provided further evidence of the pitfalls facing a businessman running for president. As noted in the earlier chapter on Ross Perot, Americans tend to be skeptical that business skills and successes are transferable to the world of politics. Only once had a man of business, Wendell Willkie in 1940, been nominated by a major party for president without having held any elected office, and Willkie won the nomination primarily on the basis of his foreign policy views! Romney was a former governor, but except for Willkie and Perot, no previous presidential candidate had so stressed experience in business as a qualification for the White House.

Perhaps the wealthiest man ever nominated for president, with a net worth of $250 million or more, Romney raised eyebrows when released tax returns revealed that he held accounts in the Cayman Islands and Switzerland, traditional havens for tax avoidance. And because most of his income was earned from investments and capital gains, he paid an effective tax rate of less than 14 percent, a lower rate than that paid by many Americans of average means.

Romney's wealth was not an asset in 2012.

Banks, Wall Street, and financiers of all stripes bore a considerable part of the blame in the public mind for the 2008 financial collapse that led to what was labeled the “Great Recession,” and income inequality was a growing national concern that led to the nebulous but troublesome “Occupy Wall Street” movement. Obama had made raising tax rates on the wealthiest 2 percent of Americans the centerpiece of his reelection campaign, while Romney proposed broad-based tax cuts that critics said disproportionately benefited the wealthy. How Romney had accumulated his wealth also became an issue. Romney claimed his work leading a private equity firm, Bain Capital, gave him expertise in job creation, but sometimes Bain's investments led to business failures and job losses.

Yet Romney's unique place among presidential candidates as a Mormon and wealthy businessman was not why many observers believed that 2012 should have been a consequential election. Rather, conservatives particularly hoped that 2012 would resolve whether social welfare programs from the Great Society and even the New Deal would be rolled back in a renewed enthusiasm for limited government, or whether, in their view, the country would continue to move to the left politically.

Partly reflecting the party realignment that had begun with Goldwater's 1964 candidacy and that was aided by McGovern's 1972 campaign, the nation seemed badly divided in 2012.

In terms of partisan identification, America had not been so evenly split since the late nineteenth century.

And by some measures, the nation, fed by an increasingly partisan news media, had never been so politically polarized.

The Republican Party was no longer just essentially a conservative party; it had evolved into an

exclusively

conservative party. The Tea Party movement, credited with energizing conservatives to a degree that allowed Republicans to sweep the 2010 midterm elections and regain control of the House, had made as one of its key goals the purging of liberals and moderates from the GOP. Long-serving Republican members of Congress whose conservative credentials had never been in question before, such as Utah Senator Bob Bennett and Indiana Senator Richard Lugar, were now described as “RINOs”â“Republicans In Name Only”âand were defeated in Republican primaries by opponents even further to the political right.

Republicans countered that Obama was moving the nation dramatically to the left with the goal of creating European-style socialism in America. Their evidence was congressional approval, without any Republican support, of the Affordable Care Act (more popularly known as “Obamacare”)âthe single most important expansion of a federal entitlement program since the creation of Medicare in 1964.

Obamacare advanced the long-held liberal goal of universal health insurance coverage for all Americans. While some components were widely popular, such as prohibiting insurance companies from denying coverage because of a pre-existing condition, universal coverage was achieved by a controversial mandate that required individuals who could afford it to purchase health insurance or pay a fine. Democrats responded to GOP outcries by claiming that they were not moving to the left so much as Republicans kept moving to the right, noting that the mandate was an idea once championed by conservatives.

One Republican who had supported the mandate in the past was Romney. Indeed, he had pioneered it as public policy in pushing for universal health insurance coverage while governor of Massachusetts. As was repeatedly noted by Obama and the Democrats, Obamacare was modeled largely off the Massachusetts experiment, which by early accounts was performing extremely well. Romney argued that what worked in Massachusetts should not necessarily be applied federally and he vowed to repeal Obamacare if elected. His was an awkward position. Romney was a candidate unable to boast about his great signature achievement as governor of Massachusetts.

With Romney appeasing his party by attacking Obamacare, conservatives hoped he would make 2012 a battle of “big ideas.” They were encouraged when Romney selected the forty-two-year-old Ryan, the chair of the House Budget Committee, to be his vice presidential nominee. Ryan had put forth a budget wildly popular in conservative circles, one that envisioned deep tax cuts, especially for the wealthy, and a dramatic change in federal entitlements. Medicare as a federal insurance program, for example, would be replaced with vouchers issued to retirees, who would use them to purchase private insurance in a competitive market.

But Ryan's budget only inspired ambiguity from Romney. At one point early in the campaign, he endorsed it, but after selecting Ryan as his running mate Romney declined to embrace it fully. Conservatives saw it as another maddening example of Romney avoiding specifics in the hope that bland generalities such as “I believe in America,” sometimes followed or preceded by Romney singing “America the Beautiful,” would suffice to persuade voters that Obama had not earned a second term. They wanted the election to offer a clear and hard choice with the expectation that voters would choose conservative principles.

Obama, too, seldom offered clear prescriptions to address the nation's many challenges. Because fewer than ten states were really up for grabs in the election, both Romney and Obama used their vast campaign funds to micro-target voters in those handful of battleground states. The 2012 contest never felt like a truly national election.

Romney's failure to define clearly the foundational principles of his campaign, during and after the election, was particularly remarkable given that Romney had said his greatest regret from his first political foray, his 1994 defeat in his race for the U.S. Senate against Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy, was that no one could easily sum up why he had run for office. A friend recalled Romney saying at the time, “After all the weeks and months of that campaign, if you ask, âWhy did Mitt Romney run for the U.S. Senate, and what did he stand for?' most people had no clue.”

After the presidential campaign, Mitt Romney's advisers acknowledged that his choice of Paul Ryan as running mate was not meant to signal an ideological campaign strategy. Rather, he was chosen for the personal chemistry Romney felt with the congressman, who was the same age as Romney's oldest son. Perhaps the trait the two men shared most was the simple love of numbers.

“I love data,” Romney told the

Wall Street Journal

editorial board during his first presidential run in 2008. “I used to call it âwallowing in the data.' . . . I want to see all the data.” When bemused

Journal

editors pressed Romney about whether such an objective approach could work in an ideologically divided age, Romney insisted that he was not devoid of a political philosophy. “I have âconcepts' that I believe,” he said. Such a seemingly disinterested approach to politics led many people, even friends and confidants, to question whether Romney had any core beliefs, or was simply an opportunist ready to take any position to close a deal.

Washington Post

columnist Ezra Klein argued that this characterization, if not unfair, was at least incomplete. “What Romney values most is something most of us don't think much about: management,” Klein wrote. “A lifetime of data has proven to him that he's extraordinarily, even uniquely, good at managing and leading organizations, projects and people. It's those skills, rather than specific policy ideas, that he sees as his unique contribution.”

Klein might have added that Romney also saw it as his inheritance, for his father, George Romney, had used his own reputation as a brilliant manager as head of the American Motors Corporation (AMC) to later win three terms as governor of Michigan, mount a serious presidential bid, and serve in Richard Nixon's Cabinet as secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

4

Â

Michael Kranish and Scott Helman, two

Boston Globe

reporters who wrote an excellent biography of Romney,

The Real Romney

, quoted a family friend who said Romney's “whole life was following a pattern which had been laid out by his dad.”

5

Romney once revealed that he had received the following advice from his father: “Don't get into politics as your profession. . . . Get into the world of the real economy. And if someday you're able to make a contribution, do it.”