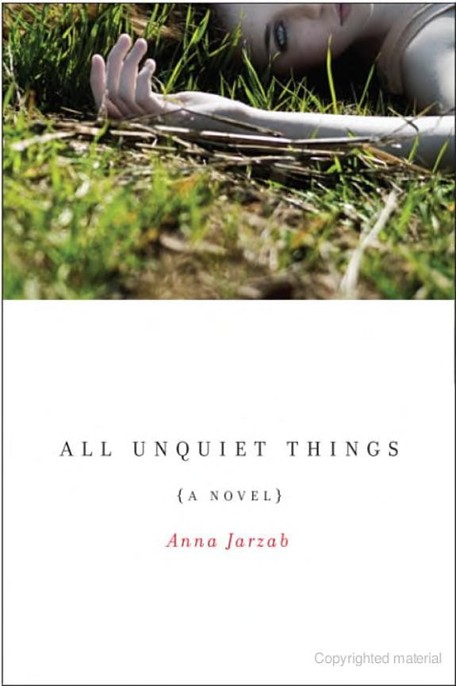

All Unquiet Things

Read All Unquiet Things Online

Authors: Anna Jarzab

For my parents, in memory of Audrey Richier

This makes the madmen who have made men mad

By their contagion; Conquerors and Kings,

Founders of sects and systems, to whom add

Sophists, Bards, Statesmen, all unquiet things

Which stir too strongly the soul’s secret springs,

And are themselves the fools to those they fool;

Envied, yet how unenviable! What stings

Are theirs! One breast laid open were a school

Which would unteach mankind the lust to shine or rule.

GEORGE GORDON, LORD BYRON

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage

It is indeed a mistake to confuse children with angels.

DOUGLAS COUPLAND

Hey Nostradamus!

P

ART

O

NE

:

Neily

P

ART

T

WO

:

Audrey

P

ART

T

HREE

:

Neily

P

ART

F

OUR

:

Audrey

E

PILOGUE

:

Neily

C

HAPTER

O

NE

Senior Year

I

t was the end of summer, when the hills were bone dry and brown; the sun beating down and shimmering up off the pavement was enough to give you heatstroke. Once winter came, Empire Valley would be compensated for five months of hot misery with three months of torrential rain, the kind of downpours that make the freeways slick and send cars sliding into one another on ribbons of oil. On the bright side, the hills would turn a green so lustrous they would look as if they had been spray painted, and in the morning the fog would transform the valley into an Arthurian landscape. But before the days got shorter and the rain came, there was the heat and the dust and the sun, conspiring to drive the whole town crazy.

School was starting on Monday. I had two more days of freedom. I hadn’t slept very much since Wednesday night; my palms were sweating, and everything ached with the ache that comes after a long hike and a couple of rough falls. My mother wanted to take me to a doctor for the insomnia, so the night before school started I didn’t go home. Instead, I went to Empire Creek Bridge, where I thought I could clear my head. The bridge was a small, overgrown stone arch, a mimicry of ancient Roman architecture that was more about form than function and could only accommodate one car at a time going one direction on its carefully placed cobblestones. A narrow, slow-moving body of water ran beneath it, and clumps of oak trees rose up near its banks. The bridge was almost useless, but very picturesque. Along one side of it was a small ledge meant for pedestrians, and this was where I lay down so that I wouldn’t get run over, and closed my eyes. I needn’t have bothered. All night, not one car passed. I could have died on that bridge and no one would have known.

This is not to say that I wanted to die. I wasn’t—and have never been—suicidal. The valley was blanketed by a late, torturous heat wave that made the shadows the only decent place to sit during the day, and the dry winds kicked up the dust, making me uneasy. I had grown up in Empire Valley and was used to these uncomfortable summers, but this time I had begun to feel a restlessness reverberating through my bones like the persistent hum of cicadas.

It had been a long, slow summer. I had spent most of it reading massive Russian novels on my porch, playing video games, and sleeping until noon. I didn’t have a lot of friends and I didn’t see much of anyone apart from my parents. I had plenty of schoolwork, too—my class schedule for the upcoming

year promised to be brutal, with six AP classes and college application season right around the corner—but nothing seemed to be able to occupy me for very long. My mother had an easy explanation for my agitation—it was my senior year and I was under a lot of pressure, especially from my father, to chart my future—but it was more complicated than that.

There was another reason I had come to Empire Creek Bridge. The year before, almost to the day, a girl I loved had died on this bridge, shot in cold blood. The police considered the matter solved—there had been an arrest, a trial, a guilty verdict—but Carly’s murder retained an air of mystery for me and so did the place where she died. I had so many questions, but nobody except Carly seemed capable of answering them, and by the time I had found her body she was already dead. Despite all the effort I had put into blocking that night from my mind and trying to forget, the murder still haunted me. I didn’t know what help spending time at the bridge would be, but I had been drawn there throughout that boiling summer, and I thought it was best to go with my instincts, even though they never seemed to do me any good.

As the sun came up that Saturday morning, I sat watching the animals—deer, hawks, the occasional wild turkey—move around on the scorched foothills. Soon, a patrol car pulled up, its siren whooping to get my attention. I had already moved from the ledge down to the creek bank, and was splashing some water on my face. The doors slammed, and I could hear footsteps making their way behind me. I felt a hand on my shoulder.

“Neily Monroe?” The officer leaned over me. “Your parents are very worried. Did you sleep here last night?”

“Yeah,” I said, though I hadn’t slept at all.

“Bryson?” The other officer was on the bridge.

Bryson stood. “He’s pretty out of it. We should get him home.”

His partner came down and took a look at me. “You feel sick?”

I nodded.

“You look sick,” he said.

“What are you doing here?” Bryson asked. “This is a park. You can’t sleep in a park overnight.”

I glanced around. “Doesn’t look like a park.”

“It is according to the city of Empire Valley.” He looked at his partner for confirmation, but the other cop just shrugged. “Anyway, it’s public property.”

“I am the public,” I said.

“You want to be a wiseass? We’ll put you in the back of that patrol car and haul you down to the station if you keep that up.” Bryson narrowed his eyes at me.

“Can’t you just write me a ticket or something?” I asked. I put my hand to my forehead, suddenly dizzy. I was hungry, too, and already sweating from the heat. I wanted my bed.

Bryson recognized me then, as I knew he would. There were very few full-time police officers in Empire Valley, which had the lowest crime rate in the Bay Area, according to the

Chronicle

. Bryson had been in the station the night I found Carly.

“What were you doing out here?” he asked again, suspicious. “Does this have anything to do with last year?”

“I don’t know.”

The other cop, whose name tag told me he was Officer Lopez, put a hand on my shoulder. “Let’s get you out of here.”

I tried to follow him up the creek bank, but I couldn’t keep my balance and fell flat in the mud. I thought it might be all right just to lie where I fell.

Bryson slipped his hands under my armpits and tugged at me. “Come on, Neily, you’ve got to help me here,” he grunted, digging his heels into the mud. “Steady as she goes there, captain. Lopez, help me get him in the car.”

“Maybe we should take him to the hospital,” Lopez suggested, and Bryson nodded.

We drove along Empire Creek Road slowly. I let my eyes go lazy and the trees blurred together. The sun was no longer showing. A blanket of clouds had blotted it out. I couldn’t help feeling relieved; maybe it would rain soon and the heat wave would end. I put my head back against the seat and closed my eyes.

At the hospital they must have given me some kind of sleeping pill or a tranquilizer, because I woke up at four-thirty on Sunday afternoon feeling gruesome. I stared at the ceiling, bringing the cracks and paint bubbles into focus. I was in my bedroom and could hear somebody moving around downstairs. It was probably my mother, but then there was a low voice, my father’s voice. The fact that he had come meant that, to them, this was serious.

I got out of bed and pulled on a pair of jeans. The room was hot and stuffy, so I quit rummaging around for a shirt and returned to the bed to gather myself. When I had left the house,

my room had been a disaster, per usual: clothes—clean and dirty—heaped in piles on the floor, papers strewn all over my desk, garbage spilling out of the trash can. My mother had been in here. She had cleaned.

I finally ambled downstairs, trying not to look so much like a zombie, although God knows for whose benefit. I caught sight of myself in the hall mirror and drew back; my skin was a pale gray, the color of chewed gum, and my dark, wavy hair, which needed a cut, was plastered against my face. There were red creases where my cheeks had been pressed against the pillows. I looked like I was about to hurl. The sedatives hadn’t sat well in my stomach; it churned at the smell of brownies coming from the kitchen. My mother had gone on a rampage of nervous baking. The kitchen counter was covered with platters, each piled high with a different baked good. My parents were at the kitchen table, arguing.