All Shook Up (3 page)

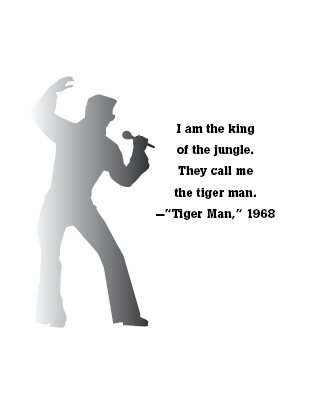

6. King of the Jungle

About twenty minutes later, my dad suddenly jumped—and I mean

jumped

—into the kitchen doing some kind of knee-bending, arm-swinging thing. I swear if there had been any food in my mouth, I’d have needed the Heimlich.

“Say hello to the King,” he shouted, balancing on one knee.

I stared at the unbelievable sight of my dad, who now looked like a Harley biker. He was dressed entirely in black: black boots and black leather pants and a black leather jacket unzipped halfway down his bare chest. A gold chain dangled around his neck. Shading his eyes were huge gold-framed sunglasses. And his face was orange. Seriously, it was.

Note to Dad: As far as I know, the real Elvis didn’t have an orange face.

“How’s my costume?” he said, stretching out his arms to give me the full effect, which showed off enough of his forty-year-old chest hair to make me feel uncomfortable. “It’s the 1968 Comeback Special outfit.”

“Comeback Special?”

“It’s what Elvis wore for his first big television show after the army and Hollywood. So whaddaya think? Can the King bring it home, son, huh?” My dad pumped his arm around in a circle and accidentally hit two plastic fish magnets, which went flying off the refrigerator.

“Bring what home?”

“It’s a saying, Josh—you know, make it happen, make it work.” My dad gave me a frustrated look, as if I wasn’t reacting the way he wanted. “That’s okay, just forget it.” He stood up slowly, creaking upward on one black leather knee, and came over to the table. I could see now that the orange color was makeup. Way too much makeup. Not only that, but his palms looked like a ballpoint pen had leaked all over them.

“What’s on your hands?”

“Lyrics.” Dad held out his left hand, showing me how the blue smudges were words crowded into every spare inch of skin. There were even words written on each of his fingers. “All the ones I keep forgetting.” He laughed and wiped away a trickle of sweat coming down his face.

Note to Dad: Please tell me you don’t actually go onstage with the lyrics written on your

hands.

“So why don’t you come along tonight, Josh, and see what my show’s like? I promise I won’t embarrass you or anything. It’ll be a good time. I’m just doing a little restaurant gig down the road. Whaddaya say?”

I think my dad really expected me to come with him. But there was no way.

No way

. Not after seeing the lyrics on his hands. And his orange face. And the ridiculous gold sunglasses. I couldn’t believe he actually went out in public, looking like he did. What did people say when they saw him at traffic lights? Or gas stations?

My dad started down the hall, talking half like Elvis and half like Jerry Denny. “You’re gonna have to hurry up, though, because the King is already running—crap—twenty minutes late.”

I called out from the kitchen that I didn’t really feel like going with him. That I just wanted to watch TV and hang out at home instead.

“You sure?” My dad’s muffled voice continued down the hall, along with a lot of thumping and banging, which I could only assume was coming from things he was attempting to carry out the door. “It’s gonna be fun….”

“That’s okay, thanks.”

“Your choice,” he answered, and pulled the front door closed with a house-shaking thud. After he left, everything was weirdly silent. The words “Elvis has left the building” went through my head. The strong smell of my dad’s hair spray, or aftershave, or whatever he was wearing still drifted in the air. An empty guitar case was sitting smack in the middle of the hallway. The house had the feeling of being suddenly abandoned. Or maybe it was me who had the feeling of being abandoned.

Sitting in the kitchen staring at the Colonel’s happy face on the chicken bucket, I tried to decide if what had happened since I’d arrived in Chicago belonged in the category of

THINGS TO TELL MY MOM

or

THINGS TO KEEP TO MYSELF

. This was a gray area for all divorced kids. It was like being a two-way mirror: you could reveal some important stuff between houses, but not everything.

From past experiences, I had learned it was not a good idea to share anything related to my parents’ current dating life, anything related to presents or money they had given to me, or anything that made one house or parent seem better than the other.

But the fact that my dad had lost his job at Murphy’s Shoes and was setting out on some crazy course to become Jerry Denny as the King seemed like something my mom ought to know. And how many nights was he really going to be gone on these “gigs”? I mean, I didn’t mind having some time on my own. I kind of liked the fact that my dad usually gave me more space than my mom, who tapped on my bedroom door about once an hour to make sure I hadn’t been abducted by aliens or knocked unconscious by kidnappers. But sitting around Chicago by myself for a few months wasn’t my idea of a good time, either.

When a phone call interrupted the silence a few minutes later, I have to admit I was pretty relieved to hear my mom’s normal voice on the other end. At least she hadn’t turned into Elvis or any other rock-and-roll legend, as far as I could tell.

“Are you unpacked and settled in yet?”

I told her yes, because my mom is a worrier and if I told her the truth—that my clothes were still jammed in my suitcases and would probably stay that way for a couple more days—I knew I would get a long lecture on taking care of my stuff, and I wasn’t really into listening to all that. Plus, if I kept my clothes packed up, there was the slim chance that maybe I could still leave Chicago.

“And how’s your dad?” she asked, which was typically the second Mom question. She said it that way every time.

Your

dad. Emphasis on the

your.

As if he was somebody she had no connection to and didn’t know very well. This always seemed bizarre to me since she had once been

married

to the guy, for cripes sake. My dad wasn’t much different when he talked about her.

“He’s okay,” I said, knowing this was the perfect opportunity to tell my mom about Murphy’s closing and Dad’s Elvis business. I could start by saying how a few things had changed since the last time I’d seen Dad—and finish by telling her it was probably a good idea if I didn’t stay in Chicago. That it would be better for everybody if I came to Florida instead.

However, unloading all of this news on my mom in the first thirty seconds of our phone call didn’t seem right, either. So I decided to wait a little longer, hoping maybe the topic would happen to come up on its own. If my mom asked me how work had been going for my dad, for instance, I’d have no choice but to tell her the truth, right?

But she had already moved on to another subject.

Chance number one, gone.

I could hear an odd waver in my mom’s voice as she told me how my grandma was not as good as she had hoped. Mom had taken a flight to Florida just a few hours after I’d left for Chicago, and this was the first time she’d seen my grandma since her accident. “She’s still in the hospital and can’t do much of anything for herself. She’s in a lot of pain, I’m afraid,” my mom said, sounding worried.

It was hard to picture my grandma in the hospital. The last time I’d seen her, she was perfectly fine. Mom and I had spent a week in June visiting her at the Shadyside Villas trailer park. Every night, she would ease into her blue recliner at six-thirty to watch the evening news, and afterward we would go with her on her “walkabout,” as she liked to call it: two laps of the trailer park at a pace that felt like being in a slow-motion movie to me.

Then the three of us would sit around the picnic table on my grandma’s porch playing Hearts or Knockout or just Solitaire if nobody was up for a real game. Grandma had taught me to play Solitaire as a little kid, when I could hardly hold the cards, let alone shuffle them. Now I took a pack of cards everywhere I went. “Everybody needs a constructive way to pass the time,” my grandma often said, which I think was a not-so-subtle reference to my grandpa George, who had passed his time by smoking and drinking too much, I guess. He’d died way before I was born, so I’d never met him—which my mom said was probably a good thing. Evidently, he wasn’t a shining role model in general.

“Grandma asked about you,” Mom continued. “She felt bad that you had to leave your school and your friends in Boston, but I told her not to worry—you are the kind of kid who can adjust to anything. Unlike your mom, who frets about everything, right?” She laughed uneasily, as if this was true—which it was. “I told your grandma that maybe this visit with your dad will turn out to be a good chance for you to spend more time with him, now that you’re getting older and can do more things together.”

And right there, I knew my best chance to say something about Dad had totally evaporated. What was I supposed to say after that?

Hey, Mom, did you know Dad is now pretending to be Elvis?

Or

Mom, guess what? Dad lost his job and he’s broke, so he’s singing at some restaurant tonight and I’m eating a bucket of cold KFC chicken by myself.

Even asking if I could come to Florida didn’t seem like a good idea. I could tell by the wobbly sound of my mom’s voice that she was totally stressed out, and I knew she was probably making up her Post-it note lists like there was no tomorrow:

THINGS TO BUY FOR GRANDMA

,

DOCTORS TO TALK TO

,

PEOPLE TO CALL

,

ERRANDS TO RUN

….

“You’re pretty quiet,” she said, as if suspecting something.

“Just tired,” I answered.

“Everything’s okay there?”

“Yeah, fine.”

“Your dad will get you signed up for school, right?”

“I guess.”

It was like playing twenty questions over the phone. I wasn’t sure what I was trying to hide, and my mom didn’t have any clue what she was trying to find out. And so it pretty much ended in a draw, with my mom saying she would call back in a day or two with an update on my grandma. “Be good for your dad,” she finished, which was what she always said, even though I was no longer five.

Of course, once I got off the phone and realized what I’d done, I decided I was the biggest moron on the planet. There had been so many chances to say something, even to give my mom a small hint, and I’d said zip. Zero. Who was I protecting? I wondered. My dad? My mom? Myself? Definitely not myself—otherwise I wouldn’t be stuck in an empty house in Chicago eating cold mashed potatoes that had hardened into something resembling crusty kindergarten paste. I would have been hopping on the next plane to Florida.

I tried to cut some of the brownies, which turned out to be burned to the bottom of the pan. When they wouldn’t come out, I finally gave up and started scraping them off the bottom with a fork and picking up the crumbs with my fingers. Then the phone rang again. It was a call for my dad, and when I told the woman my name, she laughed.

Why is the name Josh Greenwood funny to you?

I wanted to ask, but I didn’t because it was my dad’s house and his phone.

“Just tell your dad that Viv called, honey,” the woman replied cheerfully.

As if the day hadn’t already had enough bad surprises—my dad hadn’t mentioned a word about knowing anybody named Viv. And I hated being called “honey.”

7. I Ain’t Askin’ Much of You

“Who’s Viv?” I asked at breakfast the next morning, even though I knew it probably wasn’t the right time to be throwing one question after another at my dad. Sitting across from me, he seemed kind of worn-out. In the blinding morning sunlight coming through his kitchen window, I could see patches of razor stubble on his chin and his eyes looked puffy and tired. He’d gotten home from his show at about midnight. I’d heard him trip over the guitar case in the darkness.

“Viv?” my dad repeated, his voice hoarse. He took a big swallow of coffee. “What about her?”

“She called last night.”

“Oh yeah? Okay. Thanks.” My dad took a large bite of toast and acted as if this was completely uninteresting news. “I’m sure we’ll run into her eventually,” he said, chewing slowly.

From the tone of his voice, I couldn’t tell if Viv was a new girlfriend or not. I’d met quite a few of my dad’s girlfriends over the years. None of them had impressed me very much, and to be honest, there were several I had completely hated: the second-grade teacher with the frizzed out hair (Linda? Lynne?) who always asked me endless school questions. The ditzy insurance lady who drove her huge car over every curb when she turned a corner: “Oops, sorry for that little bump in the backseat!” And who could forget KPG—Killer Perfume Girlfriend? (I couldn’t remember her real name.) Her choking perfume would linger in the house for days after she left, like a toxic death cloud.

“Hey, speaking of people”—my dad snapped his fingers, as if he was trying to change the subject—“I’ve got somebody for you to meet. Once you finish up your breakfast, I’ll take you down the street and introduce you to my new friend Gladys.”

Fortunately, Gladys turned out to be a very elderly neighbor of my dad’s—not a potential girlfriend. She lived in a house with rusty white awnings, five doors down the street. A ceramic goose with a blue bonnet sat next to her front door. Even though it was almost noon when we knocked, the lady who answered the door was still dressed in her bathrobe. This made me pretty uncomfortable, although my dad didn’t seem fazed at all. “Can I help you, gentlemen?” the woman said, peering at us uncertainly through the screen door. Her hair was an odd shade of yellowish white, and the way it was standing up in clumps all over her head reminded me of the stuffing coming out of a couch.

“How are you doing today, Gladys?” my dad said loudly.

The lady blinked, leaned closer, and then beamed a wide smile of recognition. “Why, if it isn’t my boyfriend Elvis!” she exclaimed. Did everybody in Chicago know about my dad being Elvis? She pushed open the screen door. “Come in, come in, I’m not at my best this morning, but do come in.”

“Gladys, this is Josh,” my dad said, nodding in my direction as we stepped through the door. The lady reached out one of her trembling, bird wing hands to shake mine. “It’s a pleasure, young man. I don’t know how you folks find the time to keep an old lady company, I really don’t, but it’s a pleasure, that’s for sure. I always look forward to a visit by Elvis.”

Right then I had the strange feeling that maybe Gladys actually believed my father was Elvis. The real Elvis. Mr. Pelvis himself. I glanced over at my dad. Did he have that sense, too? But he was already following the old lady as she padded slowly down the hall in her pink slippers.

“Are you hungry? Can I get you boys something to eat?” she said when we got to the kitchen, which smelled like burnt toast and stale coffee. Looking around, I knew my mom would’ve had a fit at the mess: pots and pans overflowing from the sink and a table covered with old newspapers, dirty dishes, and stacks of mail. The lady began pushing the junk to one side of the table, as if clearing a space for us.

“It looks like you forgot to clean up from dinner last night, Gladys,” my dad said in a half-joking voice, “and the night before, too.” A pan of congealed chicken soup still sat on top of the stove.

Gross.

He held up the two newspapers we had picked up from her driveway on our way in. “And you didn’t want today’s papers, either, I guess.”

Gladys waved her hand in the air nonchalantly. “I can’t be bothered with all that.”

This lady was definitely senile, or losing her mind, or something, I decided. I had to admit it made me kind of nervous to be around older people who were like that—who were not

all there,

I mean. There were some people at Shadyside Villas who would shout things from their porches like, “Did you see my husband while you were out walking this evening?” My grandma would lean closer to me and whisper under her breath, “Her husband’s been dead for ten years, isn’t that a pity?” And then she’d shout back to the person, “No, I didn’t, dear, but if I do, I’ll be sure to let you know.” I always tried not to think about my grandma becoming that way someday.

“Gladys makes my scarves for me,” my dad explained, flopping down in one of the chairs as if he was planning to stay awhile. I didn’t move from where I stood, leaning against the doorway, hoping he would get the clue that I didn’t want this to be a long visit.

“And I sewed a few more yesterday,” Gladys said as she shuffled out of the room. “You just stay there, dear, and I’ll get them for you.”

Note to Dad: It’s August. Not exactly scarf weather yet.

But Gladys returned wearing an entire scarf rainbow around her neck. At least that’s what it looked like. Over the collar of her robe, she had draped a bunch of shiny silk scarves: yellow, pale blue, red, and a few purple ones. “Don’t I look lovely, boys?” she exclaimed, holding her arms out and turning around slowly so the ends of the scarves fluttered in the air like crepe paper streamers.

Second note to Dad: Please tell me you aren’t really going to wear these scarves. You’re just being nice to an old lady, right?

“A few weeks ago, I was telling Gladys how I needed a few scarves to hand out at my Elvis shows,” Dad said, reaching down to pick up a yellow one that had slipped off Gladys’s shoulders and fallen onto the floor. “Because during his shows, Elvis would give them away to people in his audience.”

Apparently, Elvis liked to use a scarf to wipe his face or his neck or his armpits during a song (seriously) and then he’d hand the scarf to some lady in the crowd, who would act like she’d just received a million dollars from him instead of a sweaty old piece of silk. “Hard to believe, but true,” Dad said, nodding.

Gladys laughed in her creaky-hinge kind of way. “And I told him, ‘Why, I have this old sewing machine just sitting in my spare bedroom collecting dust. It wouldn’t be any trouble at all to make your scarves.’” She smiled as she draped the rainbow of scarves over the back of my dad’s chair and patted his shoulder with her hand. “Who would’ve thought I’d be sewing for Elvis at my age?”

Incredibly, my dad still didn’t say anything at this point. He didn’t correct her. Didn’t tell her he was Jerry Denny, former shoe salesman. Instead, he laughed and said in his fake Elvis drawl, “Well, let’s see if the King can help you get this kitchen back in shape, ma’am.”

When we finally left Gladys’s house after spending more than an hour straightening her filthy kitchen and putting the dishes with the dried crud in the dishwasher, I didn’t even wait until we got to the end of her driveway before the words started coming out of my mouth, fast and furious. “What was THAT all about?” I spouted out first, because it was the only reasonable thing I could think of to say at that moment without getting into the specifics of what had been totally wrong about the whole situation.

“What was what all about?” My dad calmly reached down to yank up a straggly weed from a crack in the driveway concrete.

“Why’d you keep letting that lady call you Elvis?” I gestured in the direction of Gladys’s house, where she was still standing at the door. “She thinks that’s who you really are.”

My dad laughed in that annoying way of his—as if he thought everything I was saying was just one big joke. “No need to get so upset, bud,” he said, draping an arm across my shoulders. “When a friend of mine introduced me to Gladys a month or so ago because I was looking for somebody to make some scarves, I tried to explain to her how I just pretend to be Elvis and wear a costume and makeup and stuff. But then, in the middle of explaining, I decided—so what? Maybe thinking I’m the real Elvis makes her happy. And if it makes her happy, why ruin it?”

I tugged my shoulders out from underneath my father’s trying-to-be-your-buddy arm. “I just don’t get it.”

My dad gave an annoyed sigh. “What don’t you get, Josh?”

“Why you’re trying to be

freakin’ Elvis,

and why we had to help clean that lady’s kitchen,” I said under my breath, just loud enough to be heard.

“Well then why don’t you tell me what we should be doing, Josh?” My dad’s voice was getting an impatient edge to it. “Because I don’t seem to have it right, do I? I thought I was a shoe salesman. Spent fifteen years of my life in some lousy store selling high heels and sneakers, and then the place goes broke, bankrupt, overnight, and I’ve gotta figure out who I am all over again at the age of forty, which isn’t a whole lot of fun, I’ll tell you that.”

Since I could see all I was getting was a lecture, I shut up and concentrated on staring at the air, as if the molecules just in front of my nose were completely fascinating.

My dad kept on talking. He went into a long story about how Elvis always cared about ordinary people, even when he was famous. “You could be a complete stranger and he’d turn around and give you a Cadillac if he felt like it,” my dad continued. “I read about somebody who was just admiring Elvis’s car in the parking lot and Elvis came over and told the person, ‘Lady, this one’s mine, but I’ll take you to the showroom and buy a new one for you,’ and he bought her a brand-new car. Didn’t even know who she was! Gave her an eleven-thousand-dollar Cadillac,” my dad finished.

I had no idea what free Cadillacs had to do with washing Gladys’s dishes or my dad losing his job at Murphy’s, but I didn’t say anything.

“Gladys is just a lonely old lady living by herself, Josh. The only family she’s got is some worthless nephew who never shows up. We spent an hour helping her to clean her kitchen. How hard was that?” Dad bumped his elbow into my side. “And as Elvis would say, ‘Hey baby’”—he pretended to hold a microphone out to me—“‘I ain’t askin’ much of you….’”