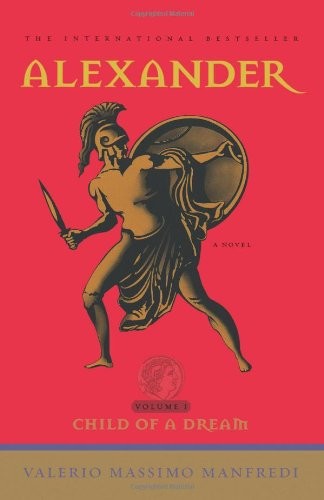

Alexander: Child of a Dream

Read Alexander: Child of a Dream Online

Authors: Valerio Massimo Manfredi

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #General

valerio massimo manfredi

‘And you, Alexander, sleepless in the dead of night:

Where do your eyes roam? Where does your heart wander? Yours is a quest for far off lands

Where the constellations set, Where the last waves of the ocean die’

A huge international bestseller, Alexander: Child of a Dream is the first in Valerio Massimo Manfredi’s outstanding trilogy of brutal passion and grand adventure in Ancient Greece.

Who could have been born to conquer the world other than a god? A boy, born to a great king - Philip of Macedon - and his sensuous queen, Olympias. Alexander became a young man of immense, unfathomable potential. Under the tutelage of the great Aristotle and with the friendship of Ptolemy and Hephaiston, he became the mightiest and most charismatic warrior, capable of subjugating the known world to his power.

A marvellous novel of one of history’s greatest characters and his quest to conquer the civilized world.

ALEXANDER: CHILD OF A DREAM

dr valerio massimo manfredi is an Italian historian, journalist and archaeologist. He is the Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Milan, and a familiar face on European television. He has published seven novels, including the bestselling Alexander trilogy, for which the American Biographical Institute voted him Man of the Year in 1999. He is married with two children and lives in a small town near Bologna. He is currently at work on a screenplay for a major Hollywood studio.

iain hallidat was born in Scotland in 1960. He studied American Studies at the University of Manchester and worked in Italy and London before moving to Sicily, where he now lives. As well as working as a translator, he currently teaches English at the University of Catania.

Also by Valerio Massimo Manfredi

alexander: the sands of ammon

valeria massimo manfredi

ALEXANDER CHILD OF A DREAM

Translated from the Italian by Iain Halliday

PAN BOOKS

First published 2001 by Macmilllan

This edition published 2001 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place London swiw pnf

Basingstoke and Oxford

Associated companies throughout the world

www macmillan com

ISBN O 330 39170 4

Copyright Š Arnoldo Mondadon Editore S p A 1998 Translation copyright Š Macmillan zooi

Originally published 1998 in Italy as Alexandras II Figlio Dei Sogno by Arnoldo Mondadon Editore S p A Milano

The right of Valerio Massimo Manfredi to be identified as the

author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved No part of this publication may be

reproduced stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or

transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic mechanical

photocopying recording or otherwise) without the prior written

permission of the publisher Any person who does any unauthorized

act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal

prosecution and civil claims for damages

‘35798642

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Set Systems Ltd Saffron Waldon Essex

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham pic Chatham Kent

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent re sold hired out

or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which

it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

To christine

the four magi slowly climbed the paths that led to the summit of the Mountain of Light. They came from the four corners of the horizon, each carrying a satchel containing fragrant wood for the rite of fire.

Wise Man of Sunset heaped cedar wood, gathered in the forest of Mount Lebanon and stripped of its bark Last of all the Wise Man of the Night laid branches of seasoned Caucasian oak, lightning struck wood dried in the highland sun Then all four drew their sacred flints from their satchels and together they struck blue sparks at the base of the small pyramid until the fire began to burn weak

at first, faltering, then ever stronger and more vigorous the vermilion tongues becoming blue and then almost white, just like the Celestial Fire, like the supernal breath of Ahura Mazda, God of Truth and Glory, Lord of Time and Life

Only the pure voice of the fire murmured its arcane poetry within the great stone tower Not even the breathing of the four men standing motionless at the very centre of their vast homeland could be heard

They watched on enrapt as the sacred flame took shape from the simple architecture of the branches arranged on the stone altar. They stared into that most pure light, into that wonderful dance of fire, lifting their prayer for the people and for the King the Great King, the King of Kings who sat far away in the splendid hall in his palace, the timeless Persepohs, in the midst of a forest of columns painted purple and gold, guarded by winged bulls and lions rampant

The air, at that hour of the morning, in that magic and solitary place, was completely still, just as it had to be for the Celestial Fire to assume the forms and the motions of its divine nature It was this nature which drove the flames ever higher towards the Empyrean, their original source

But suddenly a powerful force breathed over the flames and quenched them, as the Magi watched on in astonishment, even the red embers were suddenly transformed into black charcoal

There was no other sign, not a sound except the screech of a falcon rising up into the empty sky, neither were there any words The four men stood dumbstruck at the altar, stricken by this most sad omen, tears welling in silence

At that same moment, far away in a remote western land, a young woman trembled as she approached the oaks of an ancient sanctuary She had come to request a blessing for the child she now felt move for the first time in her womb The woman’s name was Olympias The name of her child came on the wind that blew impatiently through the age old branches, stirring the dead leaves round the bases of the giant trunks The name was

ALEXANDROS

olympias had decided to visit the Sanctuary of Dodona because of a strange premonition that had come to her as she slept alongside her husband -Philip

II, King of the Macedonians, who lay that night in a wine-and

food-sated slumber.

She had dreamed of a snake slithering slowly along the corridor outside and then entering their bed chamber silently. She could see it, but she could not move, and neither could she shout for help. The coils of the great reptile slid over the stone floor and in the moonlight that penetrated the room through the window, its scales glinted with copper and bronze reflections.

For a moment she wanted Philip to wake up and take her in his arms, to hold her against his strong, muscular chest, to caress her with his big warrior’s hands, but immediately she turned to look again on the drakon, on the huge animal that moved like a ghost, like a magic creature, like the creatures the gods summon from the bowels of the earth whenever the need arises.

Now, strangely, she was no longer afraid of it. She felt no disgust for it, indeed she felt ever more attracted and almost charmed by the sinuous movement, by the graceful and silent force.

The snake worked its way under the blankets, it slipped between her legs and between her breasts and she felt it take her, light and cold, without hurting her at all, without violence.

She dreamed that its seed mingled with the seed her husband had already thrust into her with the strength of a bull, with all the vigour of a wild boar, before he had collapsed under the weight of exhaustion and of wine.

The next day the King had put on his armour, dined with his generals on wild hog’s meat and sheep’s milk cheese, and had left to go to war This was a war against a people more barbarous than his Macedonians the Triballians, who dressed in bearskins, who wore hats of fox fur and lived along the banks of the Ister, the biggest river in Europe

All he had said to Olympias was, ‘Remember to offer sacrifices to the gods while I am away and bear me a man child, an heir who looks like me ‘

Then he had mounted his bay horse and set off at a gallop with his generals, the courtyard resounding with the noise of their steeds’ hooves, echoing with the clanging of their arms

Olympias took a warm bath following her husband’s departure and while her maidservants massaged her back with sponges steeped in essence of jasmine and Pierian roses, she sent for Artemisia, the woman who had been her wet-nurse Artemisia was aged now, but her bosom was still ample, her hips still shapely and she came from a good family, Olympias had brought her here from Epirus when she had come to marry Philip

She recounted the dream and asked, ‘Good Artemisia, what does it mean”

Artemisia had her mistress come out of the warm bath and began to dry her with towels of Egyptian linen

‘My child, dreams are always messages from the gods, but few people know how to interpret them I think you should go to the most ancient of the sanctuanes in Epirus, our homeland, to consult the Oracle of Dodona Since time immemorial the priests there have handed down the art of reading the voice of the great Zeus, father of the gods and of men The voice speaks when the wind passes through the branches of the age-old oaks of the sanctuary, when it makes their leaves whisper in spring or summer, or when it stirs the dead leaves into movement around the trunks during autumn and winter ‘

And so it was that a few days later Olympias set off towards the sanctuary that had been built in a most impressive place, in a green valley nestling among wooded mountains

Tradition had it that this was among the oldest temples on earth two

doves were said to have flown from Zeus’s hand immediately after he chased Cronus, his father, from the skies One dove had lighted on an oak at Dodona, the other on a palm tree at the Oasis of Siwa, in the midst of the burning sands of Libya And since then, in those two places, the voice of the father of the gods had made itself heard

‘What is the meaning of my dream?’ Olympias asked the priests of the sanctuary

They sat in a circle on stone seats, in the middle of a green meadow dotted with daisies and buttercups, and they listened to the wind through the leaves of the oaks They seemed rapt in thought

Then one of them said, ‘It means that the child you will bear will be the offspring of Zeus and a mortal man It means that in your womb the blood of a god has mixed with the blood of a man

‘The child you will bear will shine with a wondrous energy, but just as the flame that burns most brightly consumes the walls of the lamp and uses up more quickly the oil that feeds it, his soul may burn up the heart that houses it

‘Remember, my Queen, the story of Achilles, ancestor of your great family he was given the choice of a brief but glonous life or a long and dull one He chose the former, he sacrificed his life for a moment of blinding light’

‘Is this an inevitable fate?’ Olympias asked, apprehensively It is but one possibility,’ replied another priest ‘A man may take many roads, but some men are born with a strength that comes to them as a gift from the gods and which seeks always to return to the gods Keep this secret in your heart until the moment comes when your child’s nature will be fully manifest Be ready then for everything and anything, even to lose him, because no matter what you do you will never manage to stop him fulfilling his destiny, to stop his fame spreading to the ends of the earth’

He was still talking when the breeze that had been blowing

through the leaves of the oaks changed, almost suddenly, into a strong, warm wind from the south. In no time at all it was strong enough to bend the tops of the trees and to make the priests cover their heads with their cloaks.

The wind brought with it a thick reddish mist that darkened the entire valley, and Olympias too wrapped her cloak around her body and her head and sat motionless in the midst of the vortex, like the statue of a faceless god.

The wind subsided just as it had begun, and when the mist cleared, the statues, the pillars and the altars that embellished the sacred place were all covered in a thin layer of red dust.

The priest who had spoken last touched it with his fingertip and brought it to his lips: ‘This dust has been brought here on the Libyan wind, the breath of Zeus Ammon whose oracle sits among the palms of Siwa. This is an extraordinary happening, a remarkable portent, because the two most ancient oracles on earth, separated by enormous distances, have spoken at the same moment. Your son has heard voices that come from far away and perhaps he has understood the message. One day he will hear them again within the walls of a great sanctuary surrounded by the desert sands.’

After listening to these words, the Queen returned to the capital, to Pella, the city whose roads were dusty in summer and muddy in winter, and there she waited in fear and trembling for the day on which her child would be born.

The labour pains came one spring evening, after sunset. The women lit the lamps and Artemisia sent word for the midwife and for the physician, Nicomachus, who had been doctor to the old King, Amyntas, and who had supervised the birth of many a royal scion, both legitimate and otherwise.

Nicomachus was ready, knowing that the time was near. He put on an apron, had water heated and more lamps brought so that there would be sufficient light.

But he let the midwife approach the Queen first, because a

woman prefers to be touched by another woman at the moment when she brings her child into the world: only a woman truly knows of the pain and the solitude in which a new life is made.

King Philip, at that very moment, was laying siege to the city of Potidaea and would not have left the front line for anything in the world.

It was a long and difficult birth because Olympias had narrow hips and was of delicate constitution.

Artemisia wiped her mistress’s brow. ‘Courage, my child, push! When you see your baby you will be consoled for all the pain you must suffer now.’ She moistened Olympias’ lips with spring water from a silver bowl, which the maids refreshed continuously.

But when the pain grew to the point where Olympias almost fainted, Nicomachus intervened, guiding the midwife’s hands and ordering Artemisia to push on the Queen’s belly because she had no strength left and the baby was in distress.

He put his ear to Olympias’ lower belly and could hear that the baby’s heart was slowing down.

‘Push as hard as you can,’ he ordered Artemisia. ‘The baby must be born now.’

Artemisia leaned with all her weight on the Queen who let out one frightfully loud cry and gave birth.

Nicomachus tied the umbilical cord with linen thread, then he cut it immediately with a pair of bronze scissors and cleaned the wound with wine.

The baby began to cry and Nicomachus handed him to the women so that they could wash and dress him.

It was Artemisia who first saw his face, and she was delighted: ‘Isn’t he wonderful?’ she asked as she wiped his eyelids and nose with some wool dipped in oil.

The midwife washed his head and as she dried it she found herself exclaiming, ‘He has the hair of a child of six months and fine blond streaks. He looks like a little Eros!’

Artemisia meanwhile was dressing him in a tiny linen tunic because Nicomachus did not agree with the practice followed in most families by which newborn babies were tightly swaddled.