Alan Turing: The Enigma (62 page)

Read Alan Turing: The Enigma Online

Authors: Andrew Hodges

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology, #Computers, #History, #Mathematics, #History & Philosophy

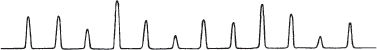

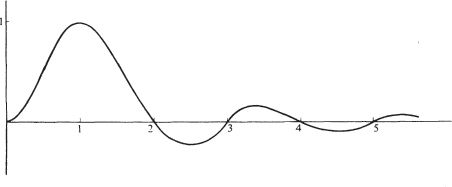

The next problem was that of how to transmit the information of these ‘spike’ heights to the receiver. In contrast to the X-system, Alan planned no quantisation of amplitudes here. He wanted to transmit them as directly as possible. In principle the ‘spikes’ themselves could be transmitted, but being of such short duration, a few microseconds in fact, they would require a channel which could carry very high frequencies. No telephone circuit could do this. To use a telephone channel the information of the ‘spikes’ would have to be encoded into an audio-frequency signal. Alan’s proposal was to feed each ‘spike’ into a specially devised electronic circuit with an ‘orthogonal’ property. This meant that its response to a spike of unit amplitude would be a wave with unit height after one time interval, and with zero height at every other unit time interval:

Assuming the circuit to be ‘linear’, meaning that the input of a ‘spike’ of say half a unit would produce exactly half of this response, the effect of feeding into it the train of ‘spikes’ would be to ‘join the dots’ in a very precise way. The information of each ‘spike’ would go exactly into the amplitude of the response of this circuit one unit of time later, and nowhere else.

The transmission would then be

straightforward, and could be achieved by perfectly standard means; the decipherment process did not require any further new ideas.

*

Apart from the question of supplying a key-system, this was all that was required for the Delilah to effect an ‘adding-on’ encipherment of speech, the analogy of what agents like Muggeridge, or the machines which produced the Fish signals, or the Rockex, were all alike doing for telegraph or teleprinter. If the key were truly ‘random’, or without any discernible pattern, such a speech cipher system would be as secure as the Vernam one-time cipher for telegraph tape, and on exactly the same argument. From the enemy’s point of view, if all keys were equally probable, then all messages would be equally likely. There would be nothing to go on.

†

The disadvantage of the simple Delilah system, as compared with the X-system, was that its output signal would be one of bandwidth 2000 Hz, rather than a stream of digits, and that it would have to be communicated perfectly, or all would be lost. In particular, any variation in time delay, or distortion in amplitudes, would ruin the decipherment process. Sender and receiver would have to keep in time to the microsecond for the same reason. This was why it could never be used for long-range short-wave transmissions. But it could be used for local short-wave, for VHF and for telephone communication. For tactical or domestic purposes, therefore, it held considerable potential.

Don Bayley was very eager to work on the Delilah, but it was not at first allowed. He was assigned to other tasks, and it only gradually became possible for him to spend time on Alan’s project. It was several months before formal permission was granted for his participation, and even then it was only on the understanding that he would have to do other jobs from time to time.

Alan’s waiting for help coincided with the time when everyone was waiting for the rather more important question of the Second Front. And it

was, after all, the enterprise for which all his efforts, fascinating and depressing alike, had helped to secure the conditions. But back at Bletchley Park there was quite a different reason for excitement in Newman’s section. They had shown that even in the time of intricate planning and coordination, there was room for initiative. In fact there had been a scramble at the last minute in the latest development of the treasure hunt. Again it was the fresh generation that had done it, disproving an assumption that something could not be done. It was something they could be proud to tell Alan Turing about.

Using the new electronic Colossus, installed since December, Jack Good and Donald Michie had made the marvellous discovery that by making manual changes while it was in operation, they could do work that hitherto it had been assumed would have to be done by hand methods in the Testery. The discovery meant that in March 1944 an order had been placed with Dollis Hill for six more Colossi by 1 June. This demand could not possibly be met, but with desperate efforts one Mark II Colossus was finished on the night of 31 May, and others followed. The Mark II included technical improvements, was five times faster, and also incorporated 2400 valves. But the essential point was that it incorporated the means for performing automatically the manual changes that Jack Good and Donald Michie had made. The original Colossus, by recognising and counting, was able to produce the best match of a given piece of pattern with the text. The new Colossus, by automating the process of varying the piece of pattern, was able to work out which was the best one to try out. This meant that it performed simple acts of decision which went much further than the ‘yes or no’ of a Bombe. The result of one counting process would determine what the Colossus was to do next. The Bombe was merely supplied with a ‘menu’; the Colossus was provided with a set of instructions.

This greatly extended the role of the machine in bringing Fish to a state of ‘cornucopian abundance’. As with the Bombe, it was not that the Colossus did everything. It was at the centre of an extremely sophisticated and complex theory, in which far from being ‘dull and elementary’, the mathematics involved was by now at the frontiers of research. There were in fact many ways in which the Colossus could be used, exploiting the flexibility offered by its variable instruction table. It took the analysts’ work into a quite new realm of enchantment. In one of the main uses, the human and the machine would work together:

12

…The analyst would sit at the typewriter output and call out instructions for a Wren to make changes in the programs. Some of the other uses were eventually reduced to decision trees and were handed over to the machine operators.

These ‘decision trees’ were like the ‘trees’ of the mechanical chess-playing schemes. It meant that some of the work of the intelligent analyst had been replaced by the electronic hardware of the Colossi; some went into

the devising of instructions for them; some into the ‘decision trees’ that could be left to uncomprehending ‘slaves’; and some retained for the human mind. When off duty, they had talked about the machines playing chess, taking intelligent decisions automatically. In their work, in this new extraordinary phase, the arbitrary dispensations of the German cryptographic system had brought something like this into being – and even more uncanny for those who did it, a sense of dialogue with the machine. The line between the ‘mechanical’ and the ‘intelligent’ was very, very slightly blurred. Whatever its application to the great surprise that awaited the Germans, they were having a wonderful time in seeing the history of the future.

No one at Hanslope, seeing the strange civilian boffin cycling across with a handkerchief around his nose (it was his hay fever period) could have connected him with the success of the assault on Normandy. And by now his part in the necessary conditions for making it was something that lay in the past; the success he wanted was of something truly and more wholly his own. As ten years before, it was his privilege to continue in his own way, with the least waste of energy, the civilisation which demanded harsher sacrifice from others. And it was another kind of invasion that he had in mind, one not yet ready for announcement.

The successful passage of 6 June 1944 roughly coincided with the point at which it became possible for Alan and Don Bayley to get down to work on constructing the Delilah equipment, clearing up the rather messy efforts that the Prof had made on his own. The main task was that of building the circuit to produce the highly accurate ‘orthogonal’ response. It was the design of this circuit that had absorbed most of Alan’s earlier thought and experiment. He had realised that it could be synthesised out of standard components. This was an entirely new idea to Don Bayley, as was the mathematics of Fourier theory

*

that had been used to attack it. It was a tough problem, which Alan said had involved spending a whole month in working out the roots of a seventh degree equation. Although he was an amateur and self-taught electronic engineer, he was able to tell his new assistant a good deal about the mathematics of circuit design, and for that matter was by now able to show most of them in the laboratory hut a thing or two about electronics. But it needed Don to bring his practical experience to bear on the problem, and to tame the straggly bird’s nest. He also kept beautifully neat notes of their experiments, and generally kept Alan in order.

Alan came in most mornings on his bicycle – sometimes in pouring rain, of which he appeared oblivious. He had

been offered the use of an official car to take him to and fro, but declined it, preferring the use of his own motive power. Once, very unusually, he was late in, and even more dishevelled than usual. As explanation he produced a grubby wad of £200 in notes, explaining that he had dug them up out of their hiding-place in a wood and that there were two silver bars still to be recovered.

But late in the summer, as the bridgehead was finally established and the Allied armies swept their way across France, he gave up his lodgings with Mrs Ramshaw at the Crown Inn, and moved to the Officers’ Mess at Hanslope Park. At first he occupied a room on the top floor of the mansion (he had one to himself, enjoying a rather more privileged status than the junior officers), and then later moved into a cottage in the walled kitchen garden, which he shared with Robin Gandy and a large tabby cat. The cat was called Timothy, and had been brought to Hanslope by Robin on his return from staying with friends in London. Alan was well-disposed towards Timothy, even though (or perhaps because) it had a way of launching playful swats at the typewriter keys when he was at work.

As a place to hibernate while they waited for the war to end, Hanslope enjoyed one special advantage. The mess officer was Bernard Walsh, the proprietor of Wheeler’s, the smart oyster restaurant in Soho. As if by magic, fresh eggs and partridges found their way on to the Hanslope dining table, while the rest of Britain chomped its way through Woolton pie and reconstituted egg. These might be supplemented by a rabbit from the copse, or a duck egg from the pond which lay at the bottom of the meadow surrounding the house, and Alan was also able to have the apple that as a rule he would always eat before going to bed. He would go out for walks or runs round the fields, and might be seen thoughtfully chewing on leaves of grass as he loped along, or perhaps burrowing around for mushrooms. During the year, a timely Penguin guide

13

to edible and inedible fungi had appeared, of which he made use to bring back amazing specimens for Mrs Lee (who organised the day-to-day catering) to cook for him. He particularly relished the name of the most poisonous of all, the Death Cap or

Amanita phalloides

. He would roll the name off his tongue with glee, and they would all search for it, but they never found a specimen.

Once of an evening he went out for a run and managed to break his ankle by slipping on a slime-covered brick which formed part of the garden path, just as he was getting into his stride. He had to be sent off in an ambulance to have it set in hospital. But at other times the Prof delighted everyone by winning the sports day race, and by defeating the young Alan Wesley (another of the March intake) who rashly challenged him to a circuit of the large field. He was accepted (with due respect to his differences) as one of a crowd of junior officers. At lunchtimes, they would gather in the mess, and look at the newspapers: the

Daily Mirror

first, for the comic strip

Jane

. Don

Bayley, who was very keen on military matters, might tell them about the developing strategy of the eastward moving armies, while Alan might hold forth on some topic of a scientific or technical flavour, such as why water was opaque to electromagnetic radiation of the radar wavelength, or how a rocket could accelerate its own fuel quickly enough. They would sometimes go for lunchtime walks together, Timothy the cat accompanying them. Robin Gandy was learning Russian – not because of his earlier membership of the Communist party (which had lapsed in 1940), but because of his admiration for the Russian classics. Robin still considered himself a fellow-traveller, and in this respect 1941 had not changed Alan’s view that he was quite misguided. But there was little discussion of politics at Hanslope, where the prevailing attitude was that of doing the job without asking questions.