Airborne (1997) (42 page)

Authors: Tom Clancy

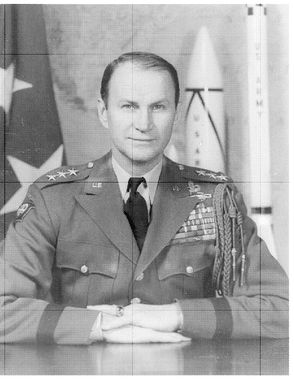

Lieutenant General James Gavin, America’s greatest Airborne leader. Even today, “Slim Jim” Gavin is the standard by which all Airborne officers are measured.

OFFICIAL U.S. ARMY PHOTO

By the time the 82nd and 101st had made good their losses and had regained their combat edge, it was midsummer. By now, General Patton’s Third Army had finally broken out of the Normandy bridgehead, and was racing, along with other British and American armies, to the pre-war borders of Nazi Germany. During this time, there were almost a dozen separate plans to use the airborne forces, now formed into the First Airborne Army, to assist in the effort to finish off Germany. Unfortunately, the Allied forces were driving so fast that none of the plans could be executed in time. Opportunity awaited, though, in the polder country of Holland.

In September 1944, the 82nd played a crucial part in Operation Market Garden, a joint American-British attempt to penetrate the Siegfried Line along a narrow front extending through Belgium, Holland, and the North German plains. The plan was ambitious not only in its aim of driving the war to Berlin in a single decisive attack, but also in concept: It was to be the first true

strategic

use of airborne troops by the Allied military, calling for parachute and glider troops to land deep behind enemy lines and seize five major bridges (and a number of other objectives) in Holland, laying a “carpet” of paratroops across the Rhine for the rapidly advancing units of the British XXX Corps. Unfortunately, the Market Garden plan was terribly flawed, resulting in a tragic setback for Allied hopes of ending the war in 1944. Some of the flaws resulted from an overly ambitious schedule for the ground forces, which were to go over 60 miles/97 kilometers in just two to four days over a single exposed road. Also, the operation was conceived and launched in just seven days, allowing a number of oversights to slip into the final details of the Market Garden plan. Then the British staff of Field Marshal Montgomery, which was planning Market Garden, ignored a number of intelligence reports from underground and Signal sources that the planned invasion route was a rest area for German units being refitted. When Market Garden started, it turned into a bloodbath for the three airborne divisions involved (the 82nd, 101st, and British 1st, along with a brigade of Polish paratroops).

strategic

use of airborne troops by the Allied military, calling for parachute and glider troops to land deep behind enemy lines and seize five major bridges (and a number of other objectives) in Holland, laying a “carpet” of paratroops across the Rhine for the rapidly advancing units of the British XXX Corps. Unfortunately, the Market Garden plan was terribly flawed, resulting in a tragic setback for Allied hopes of ending the war in 1944. Some of the flaws resulted from an overly ambitious schedule for the ground forces, which were to go over 60 miles/97 kilometers in just two to four days over a single exposed road. Also, the operation was conceived and launched in just seven days, allowing a number of oversights to slip into the final details of the Market Garden plan. Then the British staff of Field Marshal Montgomery, which was planning Market Garden, ignored a number of intelligence reports from underground and Signal sources that the planned invasion route was a rest area for German units being refitted. When Market Garden started, it turned into a bloodbath for the three airborne divisions involved (the 82nd, 101st, and British 1st, along with a brigade of Polish paratroops).

While the initial drops on September 17th went well, things began to go quickly wrong. Several of the key bridges in the south near Eindhoven (covered by the 101st) were demolished, requiring the ground forces to rebuild them, causing delays. Then the paratroops of the British 1st Para Division in the north at Arnheim found that they had dropped right on top of a pair of Waffen SS Panzer divisions (the 9th and 10th) which had been refitting. Only a single battalion made it to the Rhine bridges, where it was destroyed several days later. In the middle section around Nijmegen and Grave, things went a bit better for the 82nd, commanded by now-General Gavin. The division took most of the objectives assigned, though it failed to take the bridge over the lower Rhine near Nijmegen. Finally, in a desperate bid to take the bridge and clear the way for XXX Corps to relieve the besieged British 1 st Paras at Arnheim, Gavin took a bold gamble on September 20th. Borrowing boats from XXX Corps, he ordered Colonel Tucker’s 504th Regiment to make a crossing of the river, so that the bridge could be taken from both ends at once. Led by Major Julian Cook, several companies of the 504th made the crossing under a murderous fire, linking up with British tanks from XXX Corps, taking the bridge intact. Unfortunately, it was all for naught. XXX Corps was unable to get to Arnheim, and the remnants of the British 1st Paras were evacuated.

Thousands of Allied paratroops had been shot down for an operation that would never have been attempted had better staff planning been present. The 82nd, though, had done an outstanding job, and Gavin was clearly the rising star of the American airborne community. After holding the area around Nijmegen for a few weeks, the 82nd, along with the 101st, returned to new bases near Paris for a well-deserved refit and rest. Though Market Garden had resulted in heavy losses for the airborne corps and fallen well short of its goal, the operation had left no doubt about the 82nd’s combat efficiency. As General Gavin pointed out, the valiant men of the division accomplished all of their major tactical objectives, held firm against every counteroffensive the enemy threw at them, secured the key Nijmegen bridge in one of the war’s legendary battles, and liberated a chunk of the Netherlands that would eventually become the staging ground for the Allies’ final strikes into Germany. The airborne had at last gotten the vindication it deserved. There would be one more battle for the 82nd, though.

On December 16th, 1944, the Germans counterattacked in the Ardennes Forest in Luxembourg, trying to drive to Antwerp and split the Allied forces in half.

47

Thinly held, the Ardennes was covered by low cloud and fog, making Allied airpower useless. Unfortunately, General Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, had only two divisions in reserve to commit to the battle: the 82nd and 101st. With most of the Allied airborne leadership away on Christmas leave, it fell on General Gavin to command the two divisions, and get the most out of them. Moving into Luxembourg in trucks, Gavin emplaced the 101st in a town at the junction of a number of roads: Bastogne. Under the command of the 101st Division’s artillery commander, Brigadier General Tony McAuliffe, they were to make a legendary stand against the Germans. At one point, when ordered to surrender, McAuliffe replied with a uniquely American response: “Nuts!” Eventually, Bastogne and the 101st were relieved by General Patton’s Third Army on December 26th.

47

Thinly held, the Ardennes was covered by low cloud and fog, making Allied airpower useless. Unfortunately, General Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, had only two divisions in reserve to commit to the battle: the 82nd and 101st. With most of the Allied airborne leadership away on Christmas leave, it fell on General Gavin to command the two divisions, and get the most out of them. Moving into Luxembourg in trucks, Gavin emplaced the 101st in a town at the junction of a number of roads: Bastogne. Under the command of the 101st Division’s artillery commander, Brigadier General Tony McAuliffe, they were to make a legendary stand against the Germans. At one point, when ordered to surrender, McAuliffe replied with a uniquely American response: “Nuts!” Eventually, Bastogne and the 101st were relieved by General Patton’s Third Army on December 26th.

Famous as the fight of the 101st was, it fell to the 82nd to stop the really powerful wing of the German offensive. Gavin moved the All-Americans to the northern shoulder of the German penetration. There, around the Belgian town of Werbomont, Gavin deployed his four regiments into a “fortified goose egg,” ordering them to dig in and hold the Germans at all costs. Equipped with a new weapon, a captured supply of German-made Panzerfaust antitank rockets, the division held off the attacks of four Waffen SS Panzer divisions, blunting their attacks long enough for reinforcements to arrive and the weather to clear so that Allied airpower could destroy the German forces. The 82nd would spend a total of two months fighting in the worst winter weather on record, but it stopped the Germans cold when it counted.

Now, having fought its fifth major battle in just eighteen months, the division was again pulled back to refit. Though there was a plan to drop the 82nd into Berlin, the war ended before the plan, Operation Eclipse, could be executed. At the end of World War II, all but two of America’s airborne divisions, the 11th and the 82nd, were deactivated, with the former remaining on occupation duty in Japan, and the All-Americans coming home to American soil, and a heroes’ welcome, in the summer of 1945. It had been a hard war for the All-Americans, but they had forged a reputation for battle that still shines today.

Although airborne operations played only a limited role in the Korean War, it was during that period that the concept of

airmobility

—the idea that aircraft could deliver, support, and evacuate ground troops in remote and inhospitable terrain—began to evolve. This evolution took a giant leap forward with the development of rotary-wing aircraft (helicopters) and their extensive use in the steamy jungles of Vietnam. By 1963, CH-21 Shawnee transport helicopters and their successors, the famed UH-1B “Hueys,” had already conducted numerous missions in Southeast Asia, but it would take another year before the Army’s upper-echelon strategists grew to have full confidence in the airmobile concept—and then only because of the determination of two men: Jim Gavin and General Harry Kinnard.

airmobility

—the idea that aircraft could deliver, support, and evacuate ground troops in remote and inhospitable terrain—began to evolve. This evolution took a giant leap forward with the development of rotary-wing aircraft (helicopters) and their extensive use in the steamy jungles of Vietnam. By 1963, CH-21 Shawnee transport helicopters and their successors, the famed UH-1B “Hueys,” had already conducted numerous missions in Southeast Asia, but it would take another year before the Army’s upper-echelon strategists grew to have full confidence in the airmobile concept—and then only because of the determination of two men: Jim Gavin and General Harry Kinnard.

A seasoned World War II veteran and airborne commander, Kinnard had dropped as a lieutenant colonel with the 101st, served as the Division operations officer for the defense of Bastogne, earned the Distinguished Service Cross for his valor, and attained the rank of full colonel while still under the age of thirty. During the 1950s he and Gavin became strong proponents of the helicopter as a tactical and logistical combat aircraft.

In 1963, Kinnard was chosen to head the experimental 11th Air Assault Division and determine whether his airmobile theories would hold up in practice. The test came with a grueling, month-long series of war games with the 82nd Airborne—whose soldiers were matched against the 11th’s and its UH-1 troop carriers and gunships—that were conducted across three states and nearly five million acres of ground. In virtually every mock conflict with its crack opposition force, the trial 11th Division came out on top. Airmobility had finally gained acceptance among the top brass. As a result, the 11th AAD (Test) was redesignated the 1st Air Cavalry Division and quickly deployed to Vietnam. The 82nd’s 3rd Brigade and other units soon followed—as airmobile rather than airborne troops.

Unlike the rest of the Army, however, the 82nd stubbornly upheld its traditions, remaining the only U.S. military organization to insist that

all

its personnel be jump-qualified: a capability that has served the division well in recent times. This has been evidenced with its successful performance in several airborne operations, including Operation Just Cause (the December 1989 mission to oust General Manuel Antonio Noriega from Panama).

all

its personnel be jump-qualified: a capability that has served the division well in recent times. This has been evidenced with its successful performance in several airborne operations, including Operation Just Cause (the December 1989 mission to oust General Manuel Antonio Noriega from Panama).

Along with maintaining its airborne tradition, the 82nd has also remained the U.S. Army’s premier infantry force on the ground. Although no parachutes were seen over the skies of the Persian Gulf region during the 82nd’s hasty deployment during Desert Shield in 1990, its elite attitude served it well while holding the “line in the sand” at the vanguard of massing Coalition troops. While many of the veterans of the division’s 2nd Brigade (built around the 325th Airborne Infantry Regiment) considered themselves just “speed bumps” for Saddam Hussein’s T-72 tanks, they held the line while the rest of the Allied coalition came together. Later, they went along with the rest of XVIII Airborne Corps into Iraq, guarding the left flank of the coalition.

Finally, there was the drop that almost happened: Operation Uphold Democracy. This was to have been the three-brigade drop into Haiti which I described at the beginning of this chapter. Had it gone off, it would have been the biggest airborne operation since Market Garden. However you look at it, the 82nd is still ready to do whatever they are asked.

Currently the 82nd is designated as America’s quick-response ground force, and continues to be headquartered at Fort Bragg. It is prepared to be self-sustaining for seventy-two hours after crisis deployment, and has its own artillery, engineer, signal, intelligence, and military police aviation. With the proliferation of regional conflicts on the post-Cold War map, and the emergence of AirLand Battle doctrines synchronizing tactical air-ground operations, it is certain that the 82nd will be an indispensable component of our military presence well into the next century. Now, let’s get to know the All-Americans as they are today.

The 82nd Airborne Division: America’s Fire BrigadeDown the road from the XVIII Airborne Corps headquarters at Fort Bragg is an even bigger and more ornate building. Here, on a hill overlooking the rest of the base, is the nerve center of America’s own fire brigade, the 82nd Airborne Division. Security is tight here, perhaps even more than at the Corps headquarters. However, once you are passed through the security desk, you arrive in a world where the history and tradition wash over you like a tide. Everywhere, there are memories of the 82nd’s many battles and actions. Battle streamers hang from flags, and combat photos and prints are on every wall. This is an impressive place because, while every military unit has a headquarters, few have a tradition like the All Americans of the 82nd Airborne Division. The 82nd is a division that has done it all. From fighting in both World Wars, to having been involved in almost every U.S. military contingency and confrontation since VJ Day.

Up on the second floor is the office of the commanding general and divisional sergeant major, the leaders of this most elite of American ground units. Interestingly, my first visit here found their offices unoccupied. This is hardly unusual, though. The leadership of the 82nd is unique in the Army for its lack of ruffles and flourishes. There is also an image to uphold. The 82nd is famous for never having lost a battle or given up an inch of ground, whatever the cost. One of the prices of this reputation has been the extremely high casualty rate among senior officers within the division. Another is that every officer who can walk, and some who cannot, is expected to lead the fight from the front. During the D-Day invasion, the commander of the 2nd Battalion of the 505th Parachute Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Ben Vandervoot, broke his leg on landing. Riding in a commandeered pushcart, he led his regiment for weeks before admitting himself for treatment. Similarly, the division commander during Operation Market Garden, the immortal General James Gavin, fought the entire battle with a cracked spine, which he fractured upon landing the first day.

Other books

Teach Me Dirty by Jade West

The Pioneer Woman by Ree Drummond

Shrunk! by F. R. Hitchcock

Once Broken (Dove Creek Chronicles) by Henry, H.

Ghost's Treasure by Cheyenne Meadows

Hiss Me Deadly by Bruce Hale

The Great Christmas Ball by Joan Smith

11 Whiskey Tango Foxtrot by Heather Long

The Plan by Apryl Summers

The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain by Oppenheimer