After the Reich (59 page)

Authors: Giles MacDonogh

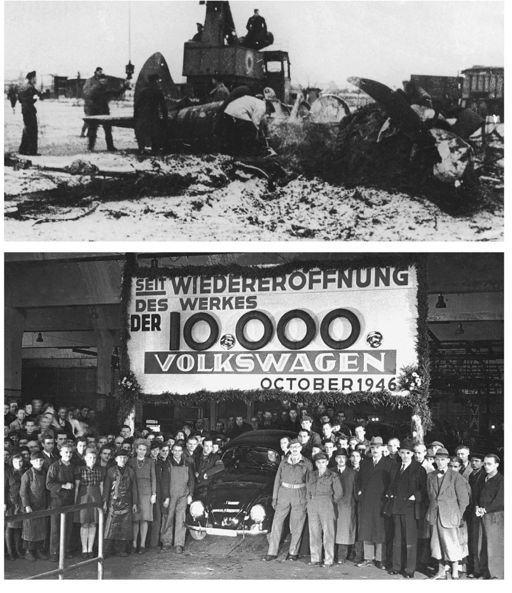

Airlift: British Pilot Officer W. K. Sewell crashes his aircraft

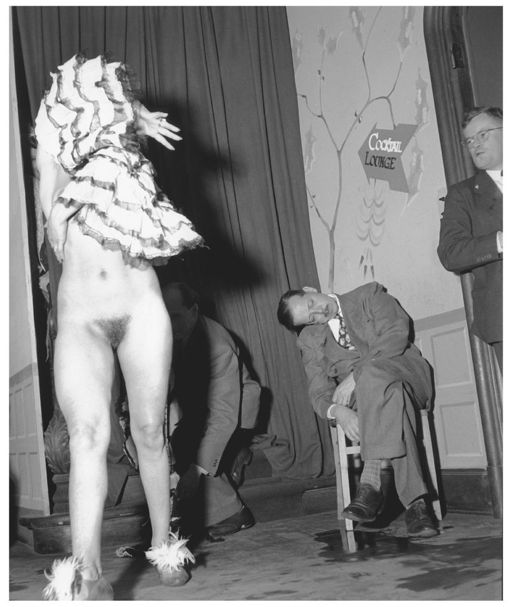

And there was plenty of fun to be had at the expense of the conquered: a drunken American officer sleeps through a striptease in his Darmstadt mess in April 1948

Culture

When Carl Zuckmayer revisited Austria, he was aware of the difficulty of distinguishing between the ‘liberated’ and the ‘occupied’ country. Despite control by four powers, Austria had its own administration, and licensing plays for performance was a mere formality. Despite that, the American authorities imposed a number of their own plays on Ernst Lothar, who was the author of the immensely successful novel

Der Engel mit der Posaune

which charted the rise of Nazism in Austria. Lothar (né Müller), who had spent the war years across the Atlantic with his wife, the actress Adrienne Gessner, was an excellent choice as American theatre chief in Vienna and he was given the job of denazifying the Viennese theatre. Naturally he felt bitter. He had told Zuckmayer that the Germans should not feel ‘pride’ for fifteen years. Zuckmayer commented to his wife Alice, ‘How good that he is only going to Austria, and to what is clearly a secondary position!’

86

Zuckmayer concluded that the Austrian film industry was in a state of ‘hopeless confusion’. The Americans had seized control of the studios in Sievering, in the suburbs of Vienna. Some of the old talent was still around, like the singer and actor Willy Forst, who had made

Wiener Madeln

(Viennese Girls) under the Nazis but never released it, because, so he said, he had wanted to save it for a non-Nazi Austria.

87

The composer Egon Wellesz did not return before 1948, and then only for a visit. When he was asked why he had taken so long, he replied no one had asked him. As Wellesz’s biographer Franz Edler has said, he was ‘The pupil and confidant of Guido Adler and would have made an exemplary successor to him at Vienna University, where he had taught before the war, but after 1945 no one even mentioned the idea.’

88

Pace

the new mayor of Vienna, Theodor Körner, many people believed that their race was still a disadvantage in Austria. Even as late as April 1948, Alfred Rosenzweig could write to Ernst Krenek in the United States that the Jewish conductor Otto Klemperer had told him he was unable to procure work in Vienna or Salzburg, adding that ‘Nazis like Herr Böhm and the Oberstandartenführer Karajan and the like, have got the lot . . .’ This was despite Allied meddling in cultural matters, with the Soviets controlling the musical scene in Vienna and the Anglo-Americans making Salzburg their flagship.

89

Richard McCreery earned a place in the hearts of the old-fashioned Viennese by bringing back flat racing at the Freudenau track in the Prater, even though it lay in the Russian Sector. His action allowed the elite Jockey Club to revive its functions, although its clubhouse opposite the Albertina had been destroyed by a direct hit in the last weeks of the war. The British had begun by organising racing in the park at Schönbrunn, which lay within their own sector. It was not long before they asked the Soviets if they could use the old course in the Prater. McCreery gave the job of organising it to his chief veterinary officer Colonel Glynn Lloyd. On 27 October 1945 six events were planned. In March the following year funds were found to award prizes. The racing began on 14 April 1946.

90

As the Russians had had the run of Vienna for months before the Western Allies arrived, they had had the pick of the buildings. The French wanted a palace for their Institut Français. The building on offer was the Palais Coburg, the magnificent residence of the dukes of Coburg overlooking the Stadtpark from its bastion on the old city wall. For some reason the French thought it too remote and coveted the Palais Lobkowitz instead. This had once been the French embassy, and it was across the way from the Albertina in a much more central position. Béthouart succeeded in wresting it from the Soviets in the course of a reception for the twenty-eighth anniversary of the Red Army. The Russians received - and trashed - the Palais Coburg instead.

Once the French were in possession of their cultural turf they could lay on concerts and exhibitions. Musicians like Jacques Thibaud and Ginette Neveu performed in its salons and lectures were delivered by the architect Le Corbusier and the artist Jean Lurçat. The Paris opera company performed

Pelléas et Mélisande

at the Theater an der Wien, the Staatsoper being bombed out. On 24 March 1947 the Comédie Française performed

Tartuffe

and Louis Jouvet’s company staged

L’Ecole des femmes

. The Viennese were also treated to French mannerists, fashions from Hermès, the Nabis, Cubism and more, while the treasures of Vienna’s museums were exposed at the Petit Palais in Paris.

Soviet Zone

The Soviet Union had always been in favour of occupying the more industrialised east of Austria. On 29 March 1945, as its troops began to cross the border from Hungary, however, it considered the southern regions of Styria and Carinthia as well. A good deal of German industry had been transferred there during the Anglo-American aerial bombardment and there was promise of rich plunder. Taking that portion too would weaken the British and strengthen the Soviet influence over Yugoslavia. As it was the Russians were able to take most of Styria before the British arrived, and help themselves to what they wanted in Graz. Not only was their arrival the signal for Tito’s partisans to enter Carinthia, the First Bulgarian Army moved up into positions in the wine region of South Styria around the small towns of Leibnitz, Radkersburg and Wildon.

91

With Styria temporarily in the Soviet Zone, virtually all Austria’s vineyards had fallen into Russian hands. Grape farmers saved what they could at their approach. In Gols in Burgenland the Stiegelmar family put the bottles in the well; the Osbergers in Strass in the Strassertal in Lower Austria resorted to the popular ruse of building a false wall to save their rarest wines. At Kloster Und near Krems, the Salomons put examples of the best vintages into the empty tuns, hoping that the Russians would be deterred by the hollow reverberations when they tapped the casks.

92

The Russian forces of occupation continued to be wild and uncontained. On Victory in Europe Day the Red Army celebrated by a new burst of looting in the course of which forty-four people lost their lives. Rape was part of daily life until 1947 and many women were riddled with VD and had no means of curing it. Burgenland suffered more than any other region of eastern Austria from the ravages of Russian solders. In Mattersburg the peasants posted guards to warn women when the Russians were about to come among them. And yet there were moments when the people had cause to thank them. For example, it was Soviet troops who built the pontoon bridge at Mautern on the Danube after the other crossings had been blown up, allowing communication to be restored between Mautern and the twin towns of Krems and Stein. It is still there, and locals call it ‘the Russian gift’.

The Allied Zones were self-contained units and it was not easy to move from one to the other, and well nigh impossible to get from the Western Allies to the Soviet Zone. Schärf maintained that it was easier to go from the Marchfeld, north-east of Vienna, to Brno in Czechoslovakia than it was to reach Salzburg in the American Zone. From Salzburg it was a simple business travelling to Munich, but much harder to make it to Vienna. To some extent this was intentional: Stalin desired a buffer zone to his satellite states in Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, and wanted to keep the Western Allies away.

93

The Russians kept a huge army in eastern Austria, based in their HQ in Baden. The command extended all the way to Romania, taking in Hungary.

The camp at Mauthausen lay near Linz in the Soviet Zone. Many French deportees had perished there and Béthouart accompanied several pilgrimages made up of bereaved families. On 20 June 1947 he went with Figl and the education minister Hurdes, both of whom had been incarcerated in Mauthausen. The Russians were notoriously half-hearted in their pursuit of Nazis, and officially left it up to the Austrian civil authorities to hunt war criminals, although they were always keen to accuse the other Allies of sheltering them. In March 1947 they claimed that the British were protecting Nazis in Carinthia. They were still supporting Yugoslav claims to territory in the southern province.

94

The Americans were keeping a record of Soviet anti-Nazi activity: in Krems the Russians rounded up 440 Nazis and put former Nazis to work clearing rubble in Gmünd and Wiener Neustadt.

cs

Half of Wiener Neustadt had been destroyed and there were outbreaks of spotted typhus.

95

British Zone

The British Zone of occupation was fraught with problems at the start. The Russians were camping in Styria, and emptying the region of any equipment of value; Bulgarians were dug in among the South Styrian vines; and the Yugoslavs had taken large parts of Carinthia. While the Bulgarians were relatively easy to control, the Russians and the Yugoslavs were a nightmare. Firstly the Yugoslavs had taken the Carinthian capital, Klagenfurt, and hoisted their flags over the city. When the local governor refused to fly a Yugoslav flag he was replaced by a more compliant figure. Posters announced that Carinthia was now part of Yugoslavia.

ct

‘National councils’ were hastily formed on which Yugoslavs and members of the Slovenian minority sat. The British were helpless. They were in the second city of Villach, forty-seven of them: twenty officers and twenty-seven administrators. Even after the British forces arrived, there were still more partisans than Tommies. ‘Shooting was out,’ although the Yugoslavs had no heavy weapons.

96

There was at least one comic moment reported by those pioneering officers in Villach. One of them was reconnoitring in the woods shortly after the British force arrived and ran into a woman in Luftwaffe uniform. She made it clear her unit was running out of food. The British officer followed her to a large underground bunker where women were pushing in and pulling out telephone plugs. It turned out to be the major military exchange for southern Austria. ‘They had known perfectly well what was happening, and had assumed that sooner or later someone would come along and give them some orders.’

97

Carinthia not Styria was the lynchpin of British foreign-political aims in the region. The goal was to prevent Trieste from falling into the wrong hands - that meant Tito. At the end of the war the New Zealanders had been sent to take the port and keep the Yugoslavs out. Trieste was to be granted to Italy in 1947, and in the meantime it was needed to supply the British and Western Allied garrisons. It was left to Field Marshal Alexander to convince the Yugoslavs to withdraw. When they refused, the British printed their own posters, accusing Tito of methods similar to Hitler’s. Byrnes’s predecessor as American secretary of state, Edward Stettinius, threatened to withdraw aid from Yugoslavia. Alexander used a line of argument that was current at the time and assured Tito that territorial settlements would be left to the ‘peace conference’. The Yugoslavs finally consented to leave on 21 May.