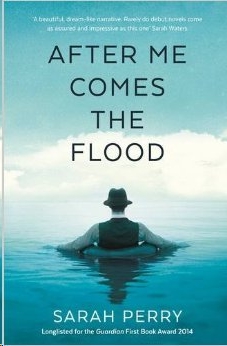

After Me Comes the Flood

Read After Me Comes the Flood Online

Authors: Sarah Perry

Sarah Perry was born in Essex in 1979, and grew up in a deeply religious home. Kept apart from contemporary culture, she spent her childhood immersed in classic literature, Victorian hymns and the King James Bible. She has a PhD in creative writing from Royal Holloway which she completed under the supervision of Andrew Motion, has been writer-in-residence at Gladstone’s Library, and is the winner of a Shiva Naipaul award for travel writing. She lives in Norwich.

Praise for

After Me Comes the Flood

‘

After Me Comes the Flood

is written in deceptively straight-forward prose that gradually yields a profound sense of foreboding. A house and the mysteries it contains; a disconcerting, dark reservoir to which everyone’s attention returns; and a most unsettling sense of place – all made me think of Fowles’

The Magus

, Maxwell’s

The Chateau

and Woolf’s

To The Lighthouse

. This is a book perhaps most deeply about the unknowability of others and of oneself – and one that, while highly disorienting and eerie, is also intensely warm. I loved it.’ Katherine Angel

‘The best novel I’ve read in a long time – an extraordinary debut from a terrific new voice who has surely got a strong future ahead of her.

After Me Comes the Flood

is at once compelling, atmospheric, intriguing, thought-provoking in spades, and impossible to forget.’ Vanessa Gebbie

AFTER ME COMES THE FLOOD

Sarah Perry

A complete catalogue record for this book can

be obtained from the British Library on request

The right of Sarah Perry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Copyright © 2014 Sarah Perry

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, dead or alive, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published in 2014 by Serpent’s Tail,

an imprint of Profile Books Ltd

3

A

Exmouth House

Pine Street

London

EC1R 0JH

eISBN 978 1 84765 946 8

For RDP

Who makes one little room an everywhere

And for Jenny

Who was always on my side

WEDNESDAY

I

I’m writing this in a stranger’s room on a broken chair at an old school desk. The chair creaks if I move, and so I must keep very still. The lid of the desk is scored with symbols that might have been made by children or men, and at the bottom of the inkwell a beetle is lying on its back. Just now I thought I saw it move, but it’s dry as a husk and must’ve died long before I came.

There’s a lamp on the floor by my feet with painted moths on the paper shade. The bulb has a covering of dust thick as felt, and I daren’t turn it on in case they see and come and find me again. There are two windows at my side, and a bright light at the end of the garden throws a pair of slanted panels on the wall. It makes this paper yellow, and the skin of my hands: they don’t look as if they have anything to do with me, and it makes me wonder where mine are, and what they’re doing. I’ve been listening for footsteps on the stairs or voices in the garden, but there’s only the sound of a household keeping quiet. They gave me too much drink – there’s a kind of buzzing in my ears and if I close my eyes they sting…

I’ve never kept a diary before – nothing ever happens to me worth the trouble of writing it down. But I hardly believe what happened today, or what I’ve done – I’m afraid that in a month’s time I’ll think it was all some foolish novel I read years ago when I was young and knew no better. I brought nothing with me, and found this notebook pushed to the back of the drawer in the desk where I sit now, hidden by newspapers buckled with damp. The paper smells dank and all the pages are empty except the last, where someone’s written the same name on every line as if they were practising a signature. It’s a strange name and I know it though I can’t remember why: EADWACER, EADWACER, EADWACER.

Underneath it I’ve written my own name down, because if I ever find this notebook again I’d like to be certain that it’s my handwriting recording these events, that I did what I have done, that it was nobody’s fault but mine. And I’ll do it again, in braver capitals than my name deserves:

JOHN COLE

, underlined three times.

I wish I could use some other voice to write this story down. I wish I could take all the books that I’ve loved best and borrow better words than these, but I’ve got to make do with an empty notebook and a man who never had a tale to tell and doesn’t know how to begin except with the beginning…

Last night I slept deeply and too long, and when I woke the sheets were tight as ropes around my legs. My throat felt parched and sore as if I’d been running, and when I put on the grey suit and grey tie I’d laid out the night before they fit me poorly like another man’s clothes.

Outside the streets were eerily quiet, and it was the thirtieth day without rain. People had begun to leave town in search of places to hide from the sun, and sometimes I wondered if I’d go out one morning and find I was the last man left. As I hurried to work there were no neighbours to greet me, and all the other shops had lowered their blinds. I’d imagined customers on the steps of the bookshop peering in at the window, wondering what had kept me, knowing I am never late – but of course no-one was waiting. No-one ever is.

When I let myself in I found that in the dim cool air of the shop I felt sick and faint. There’s an armchair I keep beside the till (it was my father’s, and whenever I sit there I expect to hear him say ‘Be off with you boy!’), and as I reached it my legs buckled and I fell onto the seat. Sweat soaked my shirt and ran into my eyes, and my head hurt, and though I’ve never understood how anyone could sleep during the day I leant against the wing of the chair and fell into a doze.

My brother says the shop fits me like a snail’s shell, and though I feign indignation to please him he’s right – I’ve never sat in that armchair, or stood behind the till, and not felt fixed in my proper place. But when I woke again just past noon everything had shifted while I slept and nothing was as I’d left it the day before. The clock in the corner sounded ill-tempered and slow, and the carpet was full of unfamiliar birds opening their beaks at me. All the same my headache had receded a little, so I stood and did a few futile little tasks, waiting for someone to come, though I think I knew no-one would. I’ve never much wanted the company of others and I’m sure they don’t want mine, but as I fumbled at the books on the shelves I was hoping for the bell above the door to ring, and for someone to stand on the threshold and hear me say ‘How can I help you?’

I crossed the empty floor to the window and looked out on the street. I heard someone calling their dog home and after that it was quieter than ever. For all that I’ve never believed it possible I felt my heart sink. It was a physical sensation as real as hunger or pain, and just as if it had been pain I felt myself grow chill with sweat. Looking for something to wipe my forehead I put my hand in my pocket, and pulled out a postcard I’d folded and shoved in there a week ago or more.

It showed a boat stranded on a marsh, and a sunrise so bleak and damp you’d think the artist intended to keep visitors away. On it someone had drawn a stick figure walking in the shallows and beckoning me in. I turned it over and saw a question mark written in green crayon, and under it the name CHRISTOPHER in letters an inch high. My brother keeps a room for me in his house on the Norfolk coast, with a narrow bed and a bookshelf where he puts the sort of novels he thinks might interest a man like me. He often says ‘Come any time: any time, mind you,’ but I never do, other than at Christmas when it seems the proper thing to do.

I turned the postcard over and over in my hands, and lifted it up as if I could smell salt rising from the marsh. If I went to see my brother, there’d be a houseful of good-natured boys, and my sister-in-law who seems always to be laughing, and my brother who’d sit up into the small hours talking over whisky. But I could put up with all of that, I thought, for clean air and a cool wind in the afternoon. So I took a sheet of cardboard from the desk, wrote CLOSED UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE on it in as tidy a set of capitals as I could manage, and propped it in the window. Then I turned off the lights and made my way home.

I’d hoped the weather might be breaking at last, but the sky was blank and bright and my head immediately began to ache. I let myself into my flat and packed a small bag, then left with the haste of a schoolboy playing truant. Twice I walked up and down the road before I found my car, feeling the heat beat like a hammer on the pavement, hardly knowing one end of the street from the other. When at last I saw it, the bonnet was covered in a fine reddish dust and someone had drawn a five-pointed star on the windscreen.

Should I have turned back then? A wiser man might have seen the journey was cursed – on a balcony above me a child was singing (we all fall down!) and in the gutter a pigeon had died on its back – but when I looked up at the windows of the flat they seemed as empty as if no-one had lived there for years.

It wasn’t until London was an hour behind me that I realised I hadn’t brought a map, or even the scrap of paper where once my brother wrote the simplest route to take. I thought I knew the way but my memory’s always playing tricks, and in less than two hours I was lost. Black boards by the roadside warned SLOW DOWN and the sun began to scorch my right arm through the glass; I opened the window, but the air that came in was foul with traffic fumes, and I began a convulsive coughing that shook my whole body at the wheel.

I began to panic. My stomach clenched like a fist, and there was a sour taste in my mouth as if I’d already been sick. My heart beat with a kind of fury that repeated itself with a new pain in my head, and I couldn’t move my hands on the wheel – nothing about me was doing what it ought and I felt as though I were coming apart in pieces. Then I thought I was losing my sight and when I realised it was nothing but steam coming from under the bonnet I shouted something – I don’t remember what, or why – and gritted my teeth, drifting on to a byroad where the traffic was sparse and slow. When the dark fringes of a familiar forest appeared I was so relieved I could almost have wept.

I drove on a little while, then finding shade pulled over and stood shaking on the bracken verge. The pines stooped over me while I vomited up a few mouthfuls of tea, then I sat on the verge with my head in my hands. When I stood again, feeling ashamed though nobody saw my disgrace, the pain behind my eyes receded and I heard nothing but the engine ticking as it cooled. I was afraid to drive again so soon – I needed to sit a while and rest, and though I know little enough about the workings of my car or any other, I thought the radiator needed water, and that I couldn’t be too far from help.

I found I’d driven almost to the road’s end, and saw ahead of me a well-trodden path so densely wooded it formed a tunnel of dim green shade. It seemed to suck at me, drawing me deeper in, so that I walked on in a kind of trance. All around I could hear little furtive movements and crickets frantically singing, and there was a lot of white bindweed growing on the verge. After a time – I don’t know how long – the path became little more than a dusty track and I found myself at the edge of a dying lawn sloping slightly upward to a distant house.

How can I explain the impression it had on me, to see it high up on the incline, the sun blazing from its windows and pricking the arrow of its weathervane? Everything about it was bright and hard-edged – the slate tiles vivid blue, the chimneys black against the sky, the green door flanked by high white columns from which a flight of steps led down towards the lawn, and to the path where I stood waiting on the boundary.

It seemed to me the most real and solid thing I’d ever seen, and at the same time only a trick of my sight in the heat. As it grew nearer it became less like a dream or invention – there were stains where ivy had been pulled from the walls, and unmatched curtains hanging in the windows. Someone had broken the spine of a book and left it open on the lawn, and near the windows rose-bushes had withered back to stumps. A ginger cat with weeping eyes was stretched out in the shade between them, panting in the sun. The painted door had peeled and blistered in the heat, and as I stood at the foot of the stairs I could see a doorknocker shaped like a man’s hand raised to rap an iron stone against an iron plate.

I was standing irresolute at the foot of the steps when someone pulled open the door and I heard a child’s voice calling. I thought they wanted someone else, who maybe stood behind me and had followed me unnoticed all the way, but when I looked over my shoulder the path was empty and I was all alone. The child laughed and called again, and I heard a name I knew from long ago, though I couldn’t think whose face it should call to mind. Then suddenly I realised it was my own name, called over and over, and the shock made me stop suddenly with my foot on the lower step. I thought: it’s only the heat, and the ringing in your ears, no-one knows you’re here.

The child’s voice came nearer and nearer, and through the blinding light I made out the figure of a girl, older than I’d first taken her for, running down the steps towards me with her arms outstretched: ‘John Cole! Is that you? It is you, isn’t it – it must be, I’m so glad. I’ve been waiting for you all day!’ I tried to find ways to explain her mistake but in my confusion fumbled with my words, and by then the girl had reached the bottom step and put her arm through mine. She said, ‘Do you know where to go? Let me show you the way’, and drew me up towards the open door. The girl went on talking – about how they’d been looking forward to meeting me, and how late I was, and how glad she was to see me at last – all the while leading me into a stone-flagged hall so dark and cold I began to shiver as the door swung shut behind me.

She must have seen my pallor and my shaking hands, because she began talking to me as if I were an old man, which I suppose I am to her. She said, ‘It’s all right, we’re nearly there’, as if these were things she’d heard were said to elderly people and thought they’d do all right for me; and all the time I was saying ‘Please don’t trouble yourself, there’s nothing wrong – I’m all right’, and neither of us listened to the other.

At the end of the dark hall we went down a stone step dipped in the centre and into a large kitchen with a vaulted ceiling. I just had time to register a dozen meat hooks hanging from their chains when she dragged out a stool for me and I nearly fell on to it. The beating behind my eyes stopped like a clock wound down leaving in its place emptiness and release, as if my head had detached itself and was drifting away. It must have been a little while later that I opened my eyes to see the girl sitting opposite me, her palms resting on the table between us. She was frowning, and examining me with unworried interest. Then she asked if I wanted water, and without waiting for a reply went over to a stone sink. I saw then how mistaken I’d been – she wasn’t a child after all, although she talked like one, rattling on in a light high voice without pausing to breathe or think. She was fairly tall, and her arms and legs were lean but also soft-looking in the way of a child. She was wearing a white T-shirt with a torn pocket on the breast. Her feet were bare and not very clean, and her face was finely made, as though it couldn’t possibly have grown out of a muddle of flesh like yours and mine, but must have been carved in stone. When she came back to the table she passed me tepid water in a chipped mug and I saw that her hair was the colour of amber, and so were her eyes, and her lips were almost as pale as the skin on her cheeks. It occurred to me that nothing about her was real.

She told me to drink up, although the country water tasted disgusting to me. Perhaps I grimaced, because she said, ‘I know – let’s have tea!’ and began to run the tap. The sound of water in the stone sink reminded me why I’d come, and all over again I started to try and explain. But she wasn’t listening – I might as well have been an animal she’d found on the steps. She said, ‘I’ve got to look after you, you see. They said: make sure he’s got everything he needs, and I said: I can do it you know, I’m not stupid.’ I still felt light-headed and could hear bells ringing in my ears, and comforted myself with the idea that the girl, the stone sink, the kettle in her hands, were not real, nor anything at all to do with me. The cat I’d seen outside appeared suddenly on the table in front of me, moving its tail like a hypnotist’s watch, and I sat following its swing. The table was scored with knife cuts and scorched with hot pans, and someone had scratched into the wood the words NOT THIS TIME.