Aesop's Fables (6 page)

Authors: Aesop,Arthur Rackham,V. S. Vernon Jones,D. L. Ashliman

Fables and Folklore

“I already know this story” is a common response, even to first-time readers of Aesop. And for good reason, for many of these fables have found their way back into the repertories of oral storytellers, thus creating for themselves a new life independent of paper and ink. Most of these tales probably came from the folk in the first place, having long circulated as retold stories before they were committed to parchment or paper. The first creation of these fables lies too far in the past for us to be able to ascertain whether a particular tale was originated by a Greek scholar, quill pen in hand, or by an illiterate grandmother entertaining her extended family with bedtime stories. Whatever their origin, many of Aesop’s fables have had a life of their own as orally told folktales, some having escaped the boundaries of the printed page at a relatively late date, others having followed unwritten folkways from the very beginning.

Folklorists use a cataloging system devised by the Finnish scholar Antti Aarne and his American counterpart Stith Thompson. The final version of this system was published in 1961 under the title

The Types of the Folktale

, and has proven itself an indispensable tool for the comparative study of international folktales. In essence, Aarne and Thompson identify some 2,500 basic folktale plots, assigning to each a type number, sometimes further differentiated by letters or asterisks. Only those Aesopic fables that have been found in folklore sources apart from Aesop have been assigned Aarne-Thompson type numbers. These fables, characteristically and understandably among the best known, are identified by their type numbers in an appendix to the present collection.

Modern Translations of AesopThe Types of the Folktale

, and has proven itself an indispensable tool for the comparative study of international folktales. In essence, Aarne and Thompson identify some 2,500 basic folktale plots, assigning to each a type number, sometimes further differentiated by letters or asterisks. Only those Aesopic fables that have been found in folklore sources apart from Aesop have been assigned Aarne-Thompson type numbers. These fables, characteristically and understandably among the best known, are identified by their type numbers in an appendix to the present collection.

Editors and translators of every age must come to terms with essentially the same questions: What text shall I use for my source? And what style shall I adopt for the finished product? As already noted, the absence of any canon or standard edition of Aesop’s fables has made the first question particularly problematic. Most modern editors use a combination of fables found in the classical editions of Phaedrus and Babrius, supplemented by various medieval and renaissance collections. As to style, well into the twentieth century most English translators of Aesop have seemed to prefer intentionally antiquated language, sprinkling their texts with archaic words and outdated grammar. Fortunately, V. S. Vernon Jones, the translator of the present collection, resisted this temptation. His English is sprightly, concise, and idiomatic, just as the everyday Greek used by the original storytellers must have been. Jones’s translation was published under the title

Æsop’s

Fables in 1912 by W. Heinemann of London. I have added footnotes, cautiously modernized the punctuation, and brought the spelling to contemporary American standards, but have made essentially no other revisions to his admirable text.

Æsop’s

Fables in 1912 by W. Heinemann of London. I have added footnotes, cautiously modernized the punctuation, and brought the spelling to contemporary American standards, but have made essentially no other revisions to his admirable text.

D. L. Ashliman

received a B.A. degree from the University of Utah, and M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Rutgers University, with additional studies at the Universities of Bonn and Göttingen in Germany. He taught folklore, mythology, German, and comparative literature at the University of Pittsburgh for thirty-three years and was emeritized in the year 2000. In addition to teaching, he held a number of administrative positions at the University of Pittsburgh, including Academic Dean for the Semester at Sea program. He also served as a guest professor in the departments of comparative literature and folklore at the University of Augsburg in Germany. D. L. Ashliman is the author of

A Guide to Folktales in the

English Language, published by Greenwood Press in 1987, as well as numerous articles and conference reports.

received a B.A. degree from the University of Utah, and M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Rutgers University, with additional studies at the Universities of Bonn and Göttingen in Germany. He taught folklore, mythology, German, and comparative literature at the University of Pittsburgh for thirty-three years and was emeritized in the year 2000. In addition to teaching, he held a number of administrative positions at the University of Pittsburgh, including Academic Dean for the Semester at Sea program. He also served as a guest professor in the departments of comparative literature and folklore at the University of Augsburg in Germany. D. L. Ashliman is the author of

A Guide to Folktales in the

English Language, published by Greenwood Press in 1987, as well as numerous articles and conference reports.

1. THE FOX AND THE GRAPES

A

hungry fox saw some fine bunches of grapes hanging from a vine that was trained along a high trellis and did his best to reach them by jumping as high as he could into the air. But it was all in vain, for they were just out of reach. So he gave up trying and walked away with an air of dignity and unconcern, remarking, “I thought those grapes were ripe, but I see now they are quite sour.”

hungry fox saw some fine bunches of grapes hanging from a vine that was trained along a high trellis and did his best to reach them by jumping as high as he could into the air. But it was all in vain, for they were just out of reach. So he gave up trying and walked away with an air of dignity and unconcern, remarking, “I thought those grapes were ripe, but I see now they are quite sour.”

2. THE GOOSE THAT LAID THE GOLDEN EGGS

A

man and his wife had the good fortune to possess a goose which laid a golden egg every day. Lucky though they were, they soon began to think they were not getting rich fast enough, and, imagining the bird must be made of gold inside, they decided to kill it in order to secure the whole store of precious metal at once. But when they cut it open they found it was just like any other goose. Thus, they neither got rich all at once, as they had hoped, nor enjoyed any longer the daily addition to their wealth.

man and his wife had the good fortune to possess a goose which laid a golden egg every day. Lucky though they were, they soon began to think they were not getting rich fast enough, and, imagining the bird must be made of gold inside, they decided to kill it in order to secure the whole store of precious metal at once. But when they cut it open they found it was just like any other goose. Thus, they neither got rich all at once, as they had hoped, nor enjoyed any longer the daily addition to their wealth.

Much wants more and loses all.

3. THE CAT AND THE MICE

T

here was once a house that was overrun with mice. A cat heard of this and said to herself, “That’s the place for me.” And off she went and took up her quarters in the house and caught the mice one by one and ate them. At last the mice could stand it no longer, and they determined to take to their holes and stay there. “That’s awkward,” said the cat to herself. “The only thing to do is to coax them out by a trick.” So she considered awhile, and then climbed up the wall and let herself hang down by her hind legs from a peg and pretended to be dead. By and by a mouse peeped out and saw the cat hanging there. “Aha!” it cried. “You’re very clever, madam, no doubt; but you may turn yourself into a bag of meal hanging there, if you like, yet you won’t catch us coming anywhere near you.”

here was once a house that was overrun with mice. A cat heard of this and said to herself, “That’s the place for me.” And off she went and took up her quarters in the house and caught the mice one by one and ate them. At last the mice could stand it no longer, and they determined to take to their holes and stay there. “That’s awkward,” said the cat to herself. “The only thing to do is to coax them out by a trick.” So she considered awhile, and then climbed up the wall and let herself hang down by her hind legs from a peg and pretended to be dead. By and by a mouse peeped out and saw the cat hanging there. “Aha!” it cried. “You’re very clever, madam, no doubt; but you may turn yourself into a bag of meal hanging there, if you like, yet you won’t catch us coming anywhere near you.”

If you are wise you won’t be deceived by the innocent airs of those whom you have once found to be dangerous.

4. THE MISCHIEVOUS DOG

T

here was once a dog who used to snap at people and bite them without any provocation, and who was a great nuisance to everyone who came to his master’s house. So his master fastened a bell round his neck to warn people of his presence. The dog was very proud of the bell, and strutted about tinkling it with immense satisfaction. But an old dog came up to him and said, “The fewer airs you give yourself the better, my friend. You don’t think, do you, that your bell was given you as a reward of merit? On the contrary, it is a badge of disgrace.”

here was once a dog who used to snap at people and bite them without any provocation, and who was a great nuisance to everyone who came to his master’s house. So his master fastened a bell round his neck to warn people of his presence. The dog was very proud of the bell, and strutted about tinkling it with immense satisfaction. But an old dog came up to him and said, “The fewer airs you give yourself the better, my friend. You don’t think, do you, that your bell was given you as a reward of merit? On the contrary, it is a badge of disgrace.”

Notoriety is often mistaken for fame.

5. THE CHARCOAL BURNER AND THE FULLER

T

here was once a charcoal burner who lived and worked by himself. A fuller,

1

however, happened to come and settle in the same neighborhood; and the charcoal burner, having made his acquaintance and finding he was an agreeable sort of fellow, asked him if he would come and share his house. “We shall get to know one another better that way,” he said, “and, besides, our household expenses will be diminished.” The fuller thanked him, but replied, “I couldn’t think of it, sir. Why, everything I take such pains to whiten would be blackened in no time by your charcoal.”

here was once a charcoal burner who lived and worked by himself. A fuller,

1

however, happened to come and settle in the same neighborhood; and the charcoal burner, having made his acquaintance and finding he was an agreeable sort of fellow, asked him if he would come and share his house. “We shall get to know one another better that way,” he said, “and, besides, our household expenses will be diminished.” The fuller thanked him, but replied, “I couldn’t think of it, sir. Why, everything I take such pains to whiten would be blackened in no time by your charcoal.”

6. THE MICE IN COUNCIL

O

nce upon a time all the mice met together in council and discussed the best means of securing themselves against the attacks of the cat. After several suggestions had been debated, a mouse of some standing and experience got up and said, “I think I have hit upon a plan which will ensure our safety in the future, provided you approve and carry it out. It is that we should fasten a bell round the neck of our enemy the cat, which will by its tinkling warn us of her approach.” This proposal was warmly applauded, and it had been already decided to adopt it, when an old mouse got upon his feet and said, “I agree with you all that the plan before us is an admirable one. But may I ask who is going to bell the cat?”

nce upon a time all the mice met together in council and discussed the best means of securing themselves against the attacks of the cat. After several suggestions had been debated, a mouse of some standing and experience got up and said, “I think I have hit upon a plan which will ensure our safety in the future, provided you approve and carry it out. It is that we should fasten a bell round the neck of our enemy the cat, which will by its tinkling warn us of her approach.” This proposal was warmly applauded, and it had been already decided to adopt it, when an old mouse got upon his feet and said, “I agree with you all that the plan before us is an admirable one. But may I ask who is going to bell the cat?”

7. THE BAT AND THE WEASELS

A

bat fell to the ground and was caught by a weasel, and was just going to be killed and eaten when it begged to be let go. The weasel said he couldn’t do that because he was an enemy of all birds on principle. “Oh, but,” said the bat, “I’m not a bird at all. I’m a mouse.” “So you are,” said the weasel, “now I come to look at you.” And he let it go. Some time after this the bat was caught in just the same way by another weasel, and, as before, begged for its life. “No,” said the weasel, “I never let a mouse go by any chance.” “But I’m not a mouse,” said the bat. “I’m a bird.” “Why, so you are,” said the weasel. And he too let the bat go.

bat fell to the ground and was caught by a weasel, and was just going to be killed and eaten when it begged to be let go. The weasel said he couldn’t do that because he was an enemy of all birds on principle. “Oh, but,” said the bat, “I’m not a bird at all. I’m a mouse.” “So you are,” said the weasel, “now I come to look at you.” And he let it go. Some time after this the bat was caught in just the same way by another weasel, and, as before, begged for its life. “No,” said the weasel, “I never let a mouse go by any chance.” “But I’m not a mouse,” said the bat. “I’m a bird.” “Why, so you are,” said the weasel. And he too let the bat go.

Look and see which way the wind blows before you commit yourself.

8. THE DOG AND THE SOW

A

dog and a sow were arguing, and each claimed that its own young ones were finer than those of any other animal. “Well,” said the sow at last, “mine can see, at any rate, when they come into the world; but yours are born blind.”

dog and a sow were arguing, and each claimed that its own young ones were finer than those of any other animal. “Well,” said the sow at last, “mine can see, at any rate, when they come into the world; but yours are born blind.”

THE FOX AND THE CROW

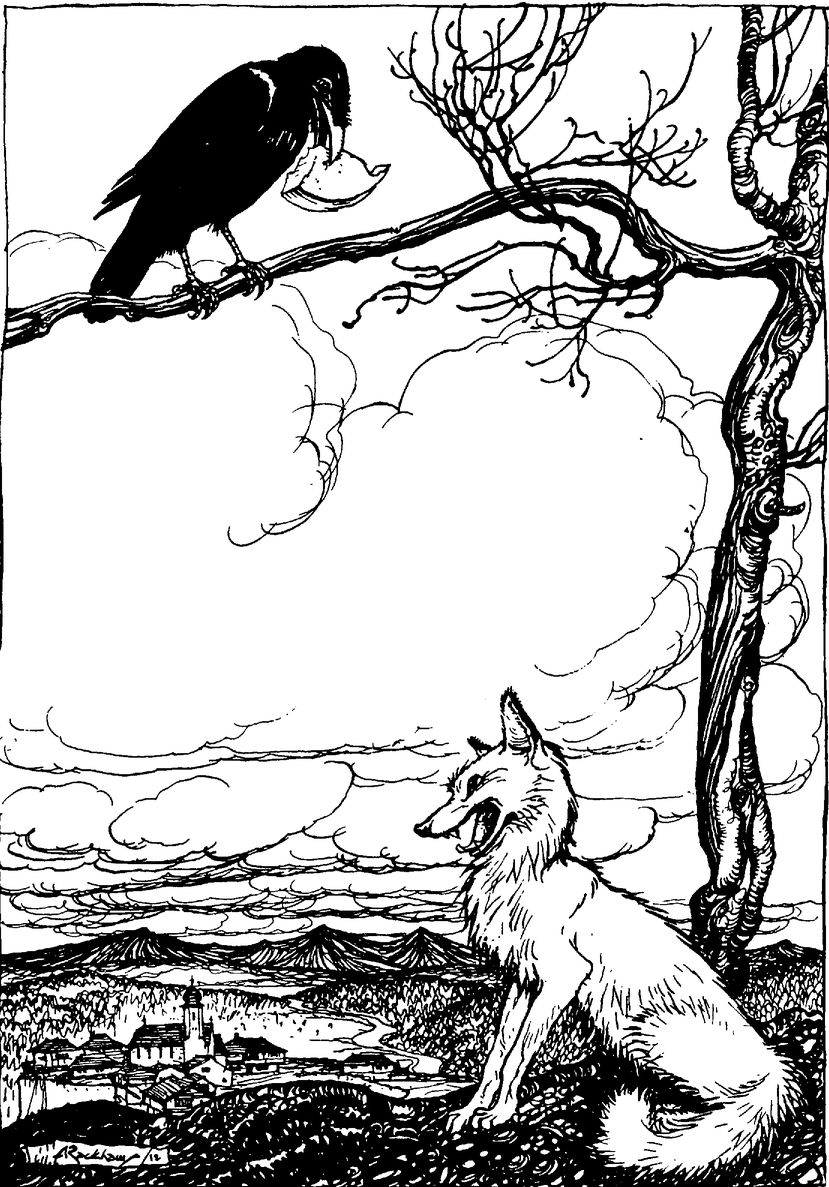

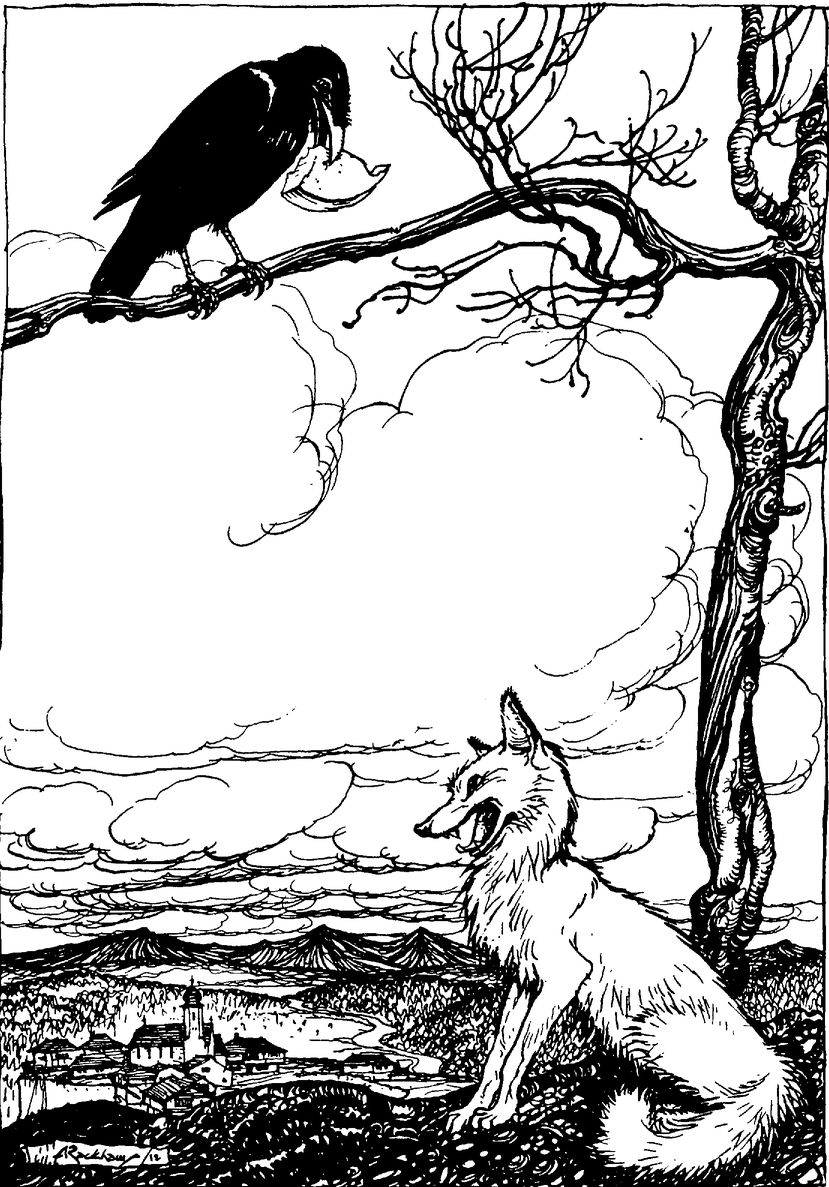

9. THE FOX AND THE CROW

A

crow was sitting on a branch of a tree with a piece of cheese in her beak when a fox observed her and set his wits to work to discover some way of getting the cheese. Coming and standing under the tree he looked up and said, “What a noble bird I see above me! Her beauty is without equal, the hue of her plumage exquisite. If only her voice is as sweet as her looks are fair, she ought without doubt to be queen of the birds.” The crow was hugely flattered by this, and just to show the fox that she could sing she gave a loud caw. Down came the cheese, of course, and the fox, snatching it up, said, “You have a voice, madam, I see. What you want is wits.”

crow was sitting on a branch of a tree with a piece of cheese in her beak when a fox observed her and set his wits to work to discover some way of getting the cheese. Coming and standing under the tree he looked up and said, “What a noble bird I see above me! Her beauty is without equal, the hue of her plumage exquisite. If only her voice is as sweet as her looks are fair, she ought without doubt to be queen of the birds.” The crow was hugely flattered by this, and just to show the fox that she could sing she gave a loud caw. Down came the cheese, of course, and the fox, snatching it up, said, “You have a voice, madam, I see. What you want is wits.”

10. THE HORSE AND THE GROOM

T

here was once a groom who used to spend long hours clipping and combing the horse of which he had charge, but who daily stole a portion of its allowance of oats, and sold it for his own profit. The horse gradually got into worse and worse condition, and at last cried to the groom, “If you really want me to look sleek and well, you must comb me less and feed me more.”

here was once a groom who used to spend long hours clipping and combing the horse of which he had charge, but who daily stole a portion of its allowance of oats, and sold it for his own profit. The horse gradually got into worse and worse condition, and at last cried to the groom, “If you really want me to look sleek and well, you must comb me less and feed me more.”

11. THE WOLF AND THE LAMB

A

wolf came upon a lamb straying from the flock, and felt some compunction about taking the life of so helpless a creature without some plausible excuse. So he cast about for a grievance and said at last, “Last year, sirrah, you grossly insulted me.” “That is impossible, sir,” bleated the lamb, “for I wasn’t born then.” “Well,” retorted the wolf, “you feed in my pastures.” “That cannot be,” replied the lamb, “for I have never yet tasted grass.” “You drink from my spring, then,” continued the wolf. “Indeed, sir,” said the poor lamb, “I have never yet drunk anything but my mother’s milk.” “Well, anyhow,” said the wolf, “I’m not going without my dinner.” And he sprang upon the lamb and devoured it without more ado.

wolf came upon a lamb straying from the flock, and felt some compunction about taking the life of so helpless a creature without some plausible excuse. So he cast about for a grievance and said at last, “Last year, sirrah, you grossly insulted me.” “That is impossible, sir,” bleated the lamb, “for I wasn’t born then.” “Well,” retorted the wolf, “you feed in my pastures.” “That cannot be,” replied the lamb, “for I have never yet tasted grass.” “You drink from my spring, then,” continued the wolf. “Indeed, sir,” said the poor lamb, “I have never yet drunk anything but my mother’s milk.” “Well, anyhow,” said the wolf, “I’m not going without my dinner.” And he sprang upon the lamb and devoured it without more ado.

12. THE PEACOCK AND THE CRANE

A

peacock taunted a crane with the dullness of her plumage. “Look at my brilliant colors,” said she, “and see how much finer they are than your poor feathers.” “I am not denying,” replied the crane, “that yours are far gayer than mine. But when it comes to flying I can soar into the clouds, whereas you are confined to the earth like any dunghill cock.”

peacock taunted a crane with the dullness of her plumage. “Look at my brilliant colors,” said she, “and see how much finer they are than your poor feathers.” “I am not denying,” replied the crane, “that yours are far gayer than mine. But when it comes to flying I can soar into the clouds, whereas you are confined to the earth like any dunghill cock.”

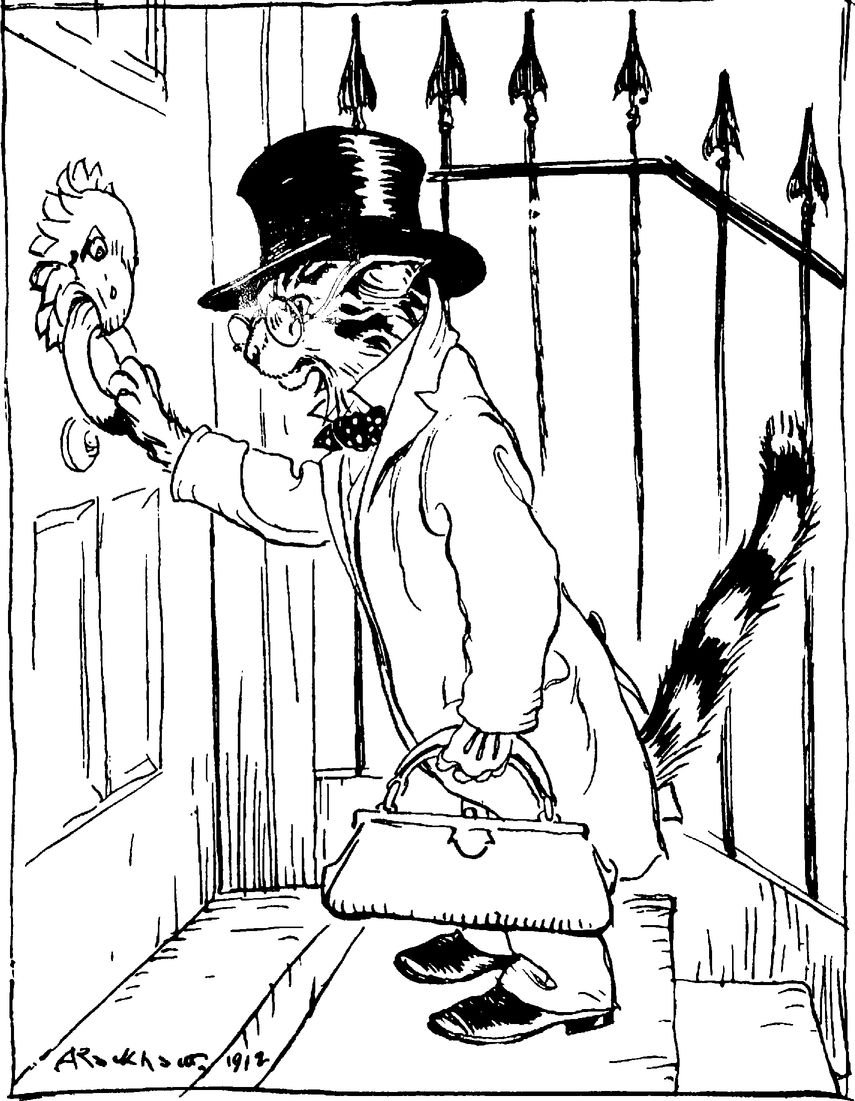

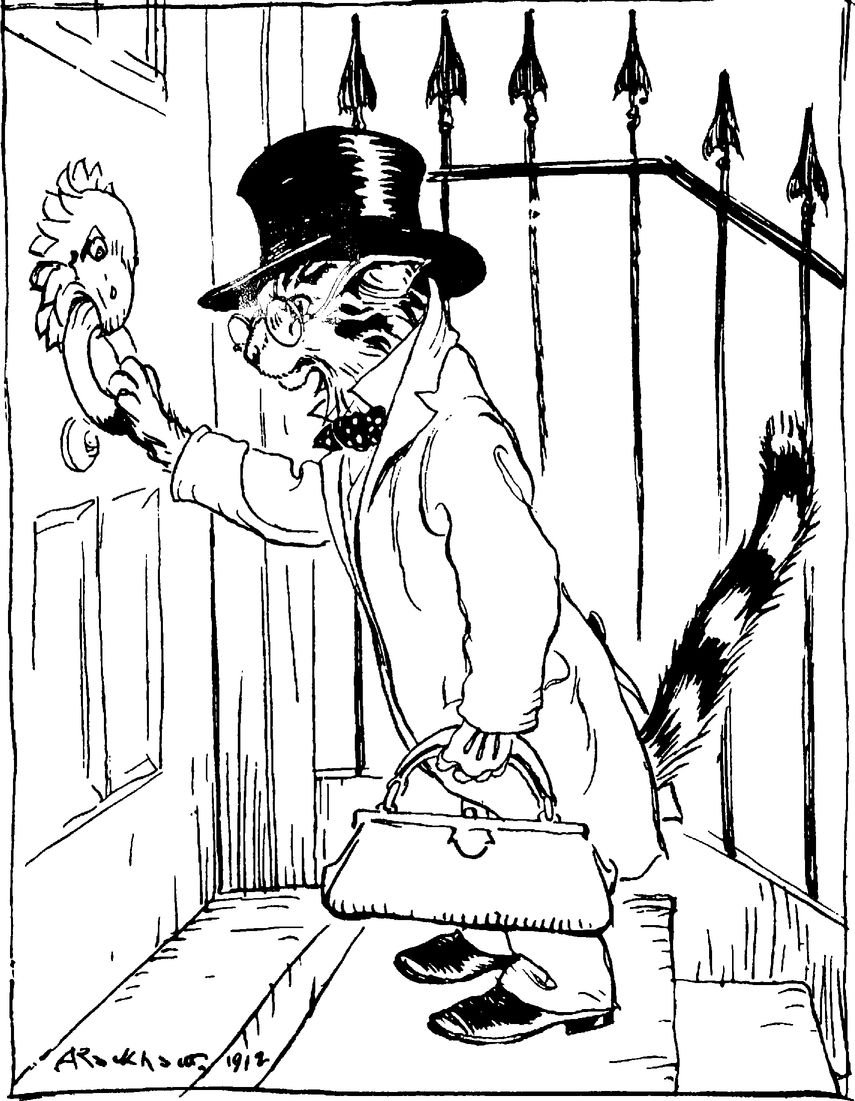

THE CAT AND THE BIRDS

13. THE CAT AND THE BIRDS

A

cat heard that the birds in an aviary were ailing. So he got himself up as a doctor, and, taking with him a set of the instruments proper to his profession, presented himself at the door, and inquired after the health of the birds. “We shall do very well,” they replied, without letting him in, “when we’ve seen the last of you.”

cat heard that the birds in an aviary were ailing. So he got himself up as a doctor, and, taking with him a set of the instruments proper to his profession, presented himself at the door, and inquired after the health of the birds. “We shall do very well,” they replied, without letting him in, “when we’ve seen the last of you.”

A villain may disguise himself, but he will not deceive the wise.

14. THE SPENDTHRIFT AND THE SWALLOW

A

spendthrift, who had wasted his fortune and had nothing left but the clothes in which he stood, saw a swallow one fine day in early spring. Thinking that summer had come and that he could now do without his coat, he went and sold it for what it would fetch. A change, however, took place in the weather, and there came a sharp frost which killed the unfortunate swallow. When the spendthrift saw its dead body he cried, “Miserable bird! Thanks to you I am perishing of cold myself.”

spendthrift, who had wasted his fortune and had nothing left but the clothes in which he stood, saw a swallow one fine day in early spring. Thinking that summer had come and that he could now do without his coat, he went and sold it for what it would fetch. A change, however, took place in the weather, and there came a sharp frost which killed the unfortunate swallow. When the spendthrift saw its dead body he cried, “Miserable bird! Thanks to you I am perishing of cold myself.”

Other books

Kaleidoscope by Ethan Spier

The Enemy by Lee Child

Glacier National Park by Mike Graf

Centaur Aisle by Piers Anthony

Ticket Home by Serena Bell

The Witch and the Huntsman by J.R. Rain, Rod Kierkegaard Jr

The Fall by Claire Merle

Suspicion by Joseph Finder

The Arrangement Anthology by H. M. Ward

What Have I Done? by Amanda Prowse