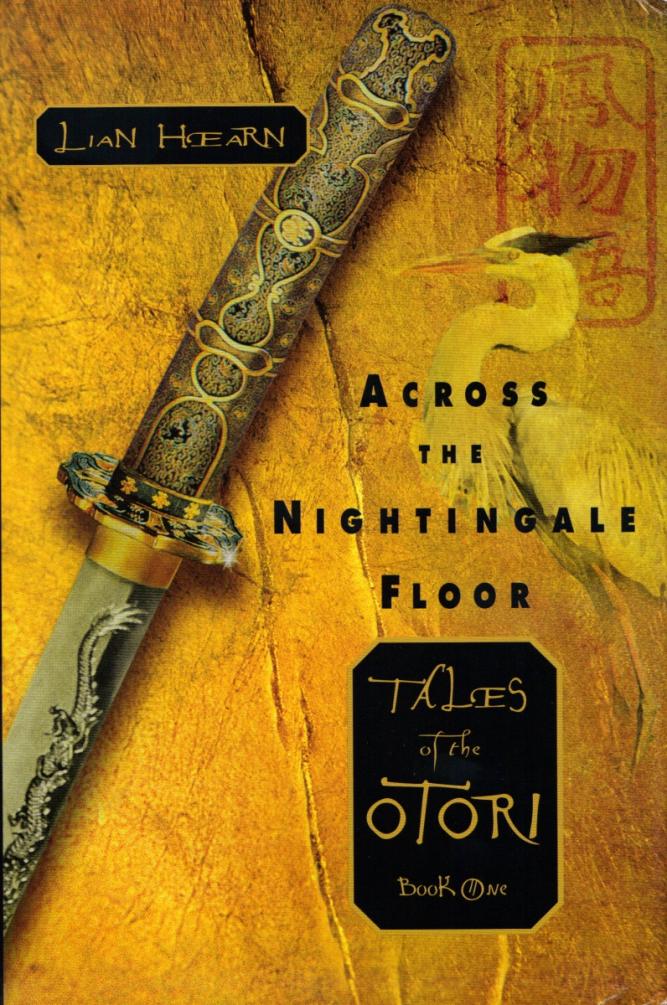

Across the Nightingale Floor

Read Across the Nightingale Floor Online

Authors: Lian Hearn

Across The Nightingale

Floor

Tales of the Otori Book 1

Lian Hearn

To E.

The three books that make up the

Tales of the Otori are set in an imaginary country in a feudal period. Neither

the setting nor the period is intended to correspond to any true historical

era, though echoes of many Japanese customs and traditions will be found, and

the landscape and seasons are those of Japan. Nightingale floors (uguisubari)

are real inventions and were constructed around many residences and temples; the

most famous examples can be seen in Kyoto at Nijo Castle and Chion'In. I have

used Japanese names for places, but these have little connection with real

places, apart from Hagi and Matsue, which are more or less in their true

geographical positions. As for characters, they are all invented, apart from

the artist Sesshu, who seemed impossible to replicate. I hope I will be

forgiven by purists for the liberties I have taken. My only excuse is that this

is a work of the imagination.

———«»———«»———«»———

The deer that weds

The autumn bush clover

They say

Sires a single fawn

And this fawn of mine

This lone boy

Sets off on a journey

Grass for his pillow

MANYOSHU VOL. 9,

NO. 1,790

My mother used to threaten to tear

me into eight pieces if I knocked over the water bucket, or pretended not to

hear her calling me to come home as the dusk thickened and the cicadas'

shrilling increased. I would hear her voice, rough and fierce, echoing through

the lonely valley. “Where's that wretched boy? I'll tear him apart when he gets

back.”

But when I did get back, muddy from

sliding down the hillside, bruised from fighting, once bleeding great spouts of

blood from a stone wound to the head (I still have the scar, like a silvered

thumbnail), there would be the fire, and the smell of soup, and my mother's

arms not tearing me apart but trying to hold me, clean my face, or straighten

my hair, while I twisted like a lizard to get away from her. She was strong

from endless hard work, and not old: She'd given birth to me before she was

seventeen, and when she held me I could see we had the same skin, although in

other ways we were not much alike, she having broad, placid features, while

mine, I'd been told (for we had no mirrors in the remote mountain village of

Mino), were finer, like a hawk's. The wrestling usually ended with her winning,

her prize being the hug I could not escape from. And her voice would whisper in

my ears the words of blessing of the Hidden, while my stepfather grumbled

mildly that she spoiled me, and the little girls, my half-sisters, jumped

around us for their share of the hug and the blessing.

So I thought it was a manner of

speaking. Mino was a peaceful place, too isolated to be touched by the savage

battles of the clans. I had never imagined men and women could actually be torn

into eight pieces, their strong, honey-colored limbs wrenched from their

sockets and thrown down to the waiting dogs. Raised among the Hidden, with all

their gentleness, I did not know men did such things to each other.

I turned fifteen and my mother

began to lose our wrestling matches. I grew six inches in a year, and by the

time I was sixteen I was taller than my stepfather. He grumbled more often,

that I should settle down, stop roaming the mountain like a wild monkey, marry

into one of the village families. I did not mind the idea of marriage to one of

the girls I'd grown up with, and that summer I worked harder alongside him,

ready to take my place among the men of the village. But every now and then I

could not resist the lure of the mountain, and at the end of the day I slipped

away, through the bamboo grove with its tall, smooth trunks and green slanting

light, up the rocky path past the shrine of the mountain god, where the

villagers left offerings of millet and oranges, into the forest of birch and

cedar, where the cuckoo and the nightingale called enticingly, where I watched

foxes and deer and heard the melancholy cry of kites overhead.

That evening I'd been right over

the mountain to a place where the best mushrooms grew. I had a cloth full of

them, the little white ones like threads, and the dark orange ones like fans. I

was thinking how pleased my mother would be, and how the mushrooms would still

my stepfather's scolding. I could already taste them on my tongue. As I ran through

the bamboo and out into the rice fields where the red autumn lilies were

already in flower, I thought I could smell cooking on the wind.

The village dogs were barking, as

they often did at the end of the day. The smell grew stronger and turned acrid.

I was not frightened, not then, but some premonition made my heart start to

beat more quickly. There was a fire ahead of me.

Fires often broke out in the

village: Almost everything we owned was made of wood or straw. But I could hear

no shouting, no sounds of the buckets being passed from hand to hand, none of

the usual cries and curses. The cicadas shrilled as loudly as ever; frogs were

calling from the paddies. In the distance thunder echoed round the mountains.

The air was heavy and humid.

I was sweating, but the sweat was

turning cold on my forehead. I jumped across the ditch of the last terraced

field and looked down to where my home had always been. The house was gone.

I went closer. Flames still crept

and licked at the blackened beams. There was no sign of my mother or my

sisters. I tried to call out, but my tongue had suddenly become too big for my

mouth, and the smoke was choking me and making my eyes stream. The whole

village was on fire, but where was everyone?

Then the screaming began.

It came from the direction of the

shrine, around which most of the houses clustered. It was like the sound of a

dog howling in pain, except the dog could speak human words, scream them in

agony. I thought I recognized the prayers of the Hidden, and all the hair stood

up on my neck and arms. Slipping like a ghost between the burning houses, I

went towards the sound.

The village was deserted. I could

not imagine where everyone had gone. I told myself they had run away: My mother

had taken my sisters to the safety of the forest. I would go and find them just

as soon as I had found out who was screaming. But as I stepped out of the alley

into the main street I saw two men lying on the ground. A soft evening rain was

beginning to fall and they looked surprised, as though they had no idea why

they were lying there in the rain. They would never get up again, and it did

not matter that their clothes were getting wet.

One of them was my stepfather.

At that moment the world changed

for me. A kind of fog rose before my eyes, and when it cleared nothing seemed

real. I felt I had crossed over to the other world, the one that lies alongside

our own, that we visit in dreams. My stepfather was wearing his best clothes.

The indigo cloth was dark with rain and blood. I was sorry they were spoiled:

He had been so proud of them.

I stepped past the bodies, through

the gates and into the shrine. The rain was cool on my face. The screaming

stopped abruptly.

Inside the grounds were men I did

not know. They looked as if they were carrying out some ritual for a festival.

They had cloths tied round their heads; they had taken off their jackets and

their arms gleamed with sweat and rain. They were panting and grunting,

grinning with white teeth, as though killing were as hard work as bringing in the

rice harvest.

Water trickled from the cistern

where you washed your hands and mouth to purify yourself on entering the

shrine. Earlier, when the world was normal, someone must have lit incense in

the great cauldron. The last of it drifted across the courtyard, masking the

bitter smell of blood and death.

The man who had been torn apart lay

on the wet stones. I could just make out the features on the severed head. It

was Isao, the leader of the Hidden. His mouth was still open, frozen in a last

contortion of pain.

The murderers had left their

jackets in a neat pile against a pillar. I could see clearly the crest of the

triple oak leaf. These were Tohan men, from the clan capital of Inuyama. I

remembered a traveler who had passed through the village at the end of the

seventh month. He'd stayed the night at our house, and when my mother had

prayed before the meal, he had tried to silence her. “Don't you know that the

Tohan hate the Hidden and plan to move against us? Lord Iida has vowed to wipe

us out,” he whispered. My parents had gone to Isao the next day to tell him,

but no one had believed them. We were far from the capital, and the power

struggles of the clans had never concerned us. In our village the Hidden lived

alongside everyone else, looking the same, acting the same, except for our

prayers. Why would anyone want to harm us? It seemed unthinkable.

And so it still seemed to me as I

stood frozen by the cistern. The water trickled and trickled, and I wanted to

take some and wipe the blood from Isao's face and gently close his mouth, but I

could not move. I knew at any moment the men from the Tohan clan would turn,

and their gaze would fall on me, and they would tear me apart. They would have

neither pity nor mercy. They were already polluted by death, having killed a

man within the shrine itself.

In the distance I could hear with

acute clarity the drumming sound of a galloping horse. As the hoofbeats drew

nearer I had the sense of forward memory that comes to you in dreams. I knew

who I was going to see, framed between the shrine gates. I had never seen him

before in my life, but my mother had held him up to us as a sort of ogre with

which to frighten us into obedience: Don't stray on the mountain, don't play by

the river, or Iida will get you! I recognized him at once. Iida Sadamu, lord of

the Tohan.

The horse reared and whinnied at

the smell of blood. Iida sat as still as if he were cast in iron. He was clad

from head to foot in black armor, his helmet crowned with antlers. He wore a

short black beard beneath his cruel mouth. His eyes were bright, like a man

hunting deer.

Those bright eyes met mine. I knew

at once two things about him: first, that he was afraid of nothing in heaven or

on earth; second, that he loved to kill for the sake of killing. Now that he

had seen me, there was no hope.

His sword was in his hand. The only

thing that saved me was the horse's reluctance to pass beneath the gate. It

reared again, prancing backwards. Iida shouted. The men already inside the

shrine turned and saw me, crying out in their rough Tohan accents. I grabbed

the last of the incense, hardly noticing as it seared my hand, and ran out

through the gates. As the horse shied towards me I thrust the incense against

its flank. It reared over me, its huge feet flailing past my cheeks. I heard

the hiss of the sword descending through the air. I was aware of the Tohan all

around me. It did not seem possible that they could miss me, but I felt as if I

had split in two. I saw Iida's sword fall on me, yet I was untouched by it. I lunged

at the horse again. It gave a snort of pain and a savage series of bucks. Iida,

unbalanced by the sword thrust that had somehow missed its target, fell forward

over its neck and slid heavily to the ground.

Horror gripped me, and in its wake

panic. I had unhorsed the lord of the Tohan. There would be no limit to the

torture and pain to atone for such an act. I should have thrown myself to the

ground and demanded death. But I knew I did not want to die. Something stirred

in my blood, telling me I would not die before Iida. I would see him dead

first.

I knew nothing of the wars of the

clans, nothing of their rigid codes and their feuds. I had spent my whole life

among the Hidden, who are forbidden to kill and taught to forgive each other.

But at that moment Revenge took me as a pupil. I recognized her at once and

learned her lessons instantly. She was what I desired; she would save me from

the feeling that I was a living ghost. In that split second I took her into my

heart. I kicked out at the man closest to me, getting him between the legs,

sank my teeth into a hand that grabbed my wrist, broke away from them, and ran

towards the forest.

Three of them came after me. They

were bigger than I was and could run faster, but I knew the ground, and

darkness was falling. So was the rain, heavier now, making the steep tracks of

the mountain slippery and treacherous. Two of the men kept calling out to me,

telling me what they would take great pleasure in doing to me, swearing at me

in words whose meaning I could only guess, but the third ran silently, and he

was the one I was afraid of. The other two might turn back after a while, get

back to their maize liquor or whatever foul brew the Tohan got drunk on, and

claim to have lost me on the mountain, but this other one would never give up.

He would pursue me forever until he had killed me.