Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD (15 page)

Read Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD Online

Authors: Martin A. Lee,Bruce Shlain

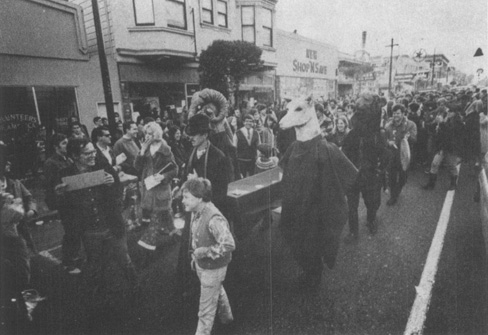

Kesey and the Pranksters hosted a series of aid tests on the West Coast.

Thousands “freaked freely” at the three-day Trip Festival in Fransico, January 1966.

(Eugene Anthony)

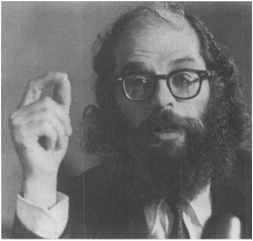

Allen Ginsberg, poet laureate of the acid subculture, shown testifying at Senate hearings on drug abuse. Ginsberg stated that there had been a “journalistic exaggeration” of the dangers of LSD.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

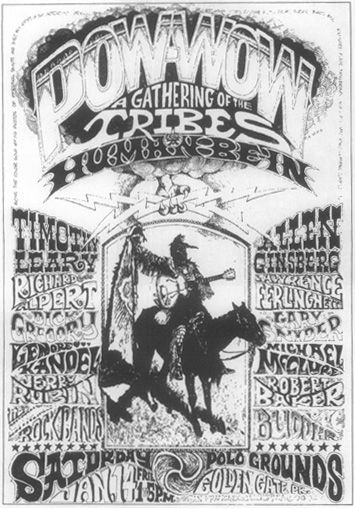

Poster announcing the first human be-in.

25,000 gathered in Golden Gate Park for the first human be-in, January 1967.

(Eugene Anthony)

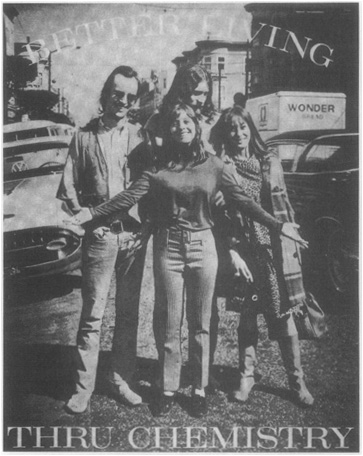

Slogan adopted by the flower children.

Anti-war demonstrates at the Pentagon, October 1967.

(Paul Conklin, Time)

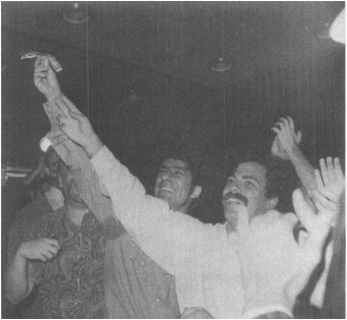

Yippies Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin burning money at the New York Stock Exchange.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

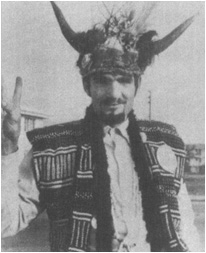

Undercover police agent posing as a hippie radical.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

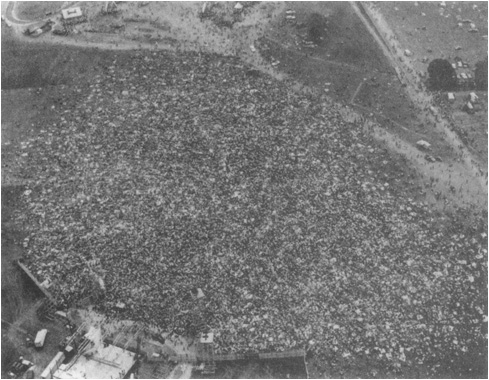

Woodstock rock festival, August 1969.

(New York Daily News Photos)

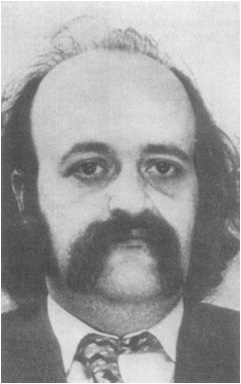

Ronald Stark manufactured 50 million hits of black market LSD in the late 1960‘s and early 1970‘s. He was later exposed as a CIA informant by Italian authorities.

(Ansa)

3

Under The Mushroom, Over The Rainbow

MANNA FROM HARVARD

Henry Luce, president of Time-Life, was a busy man during the Cold War. As the preeminent voice of Eisenhower, Dulles, and Pax Americana, he encouraged his correspondents to collaborate with the CIA, and his publishing empire served as a longtime propaganda asset for the Agency. But Luce managed to find the time to experiment with LSD—not for medical reasons, but simply to experience the drug and glean whatever pleasures and insights it might afford. An avid fan of psychedelics, he turned on a half-dozen times in the late 1950s and early 1960s under the supervision of Dr. Sidney Cohen. On one occasion the media magnate claimed he talked to God on the golf course and found that the Old Boy was pretty much on top of things. During another trip the tone-deaf publisher is said to have heard music so enchanting that he walked into a cactus garden and began conducting a phantom orchestra.

Dr. Cohen, attached professionally to UCLA and the Veterans Hospital in Los Angeles, also turned on Henry’s wife, Clare Boothe Luce, and a number of other influential Americans. “Oh, sure, we all took acid. It was a creative group—my husband and I and Huxley and [Christopher] Isherwood,” recalled Mrs. Luce, who was, by all accounts, the

grande dame

of postwar American politics. (More recently she served as a member of President Reagan’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, which oversees covert operations conducted by the CIA.) LSD was fine by Mrs. Luce as long as it remained strictly a drug for the doctors and their friends in the ruling class. But she didn’t like the idea that others might also want to partake of the experience. “We wouldn’t want everyone doing too much of a good thing,” she explained.

By this time, however, psychedelic drugs already had a certain notoriety, largely due to favorable reports in Luce’s publishing outlets. In May 1957

Life

magazine ran a story on the discovery of the “magic mushroom” as part of its Great Adventure series. Written by R. Gordon Wasson, the seventeen-page spread, complete with color photos, was laudatory in every way. Wasson, a vice-president of J. P. Morgan and Company, pursued a lifelong interest in mushrooms as a personal hobby. He and his wife, Valentina, journeyed all over the world, treading a unique path through the back roads of history in an effort to learn about the role of toadstools in primitive societies. Their travels took them to the remote highlands of Mexico, where they met a medicine woman who agreed to serve them teon-anacatl, or “God’s flesh,” as the divine mushrooms were called. As he chewed the bitter fungus, Wasson was determined to resist its effects so as to better observe the ensuing events. But as he explained to the readers of

Life,

his resolve “soon melted before the onslaught of the mushrooms.”