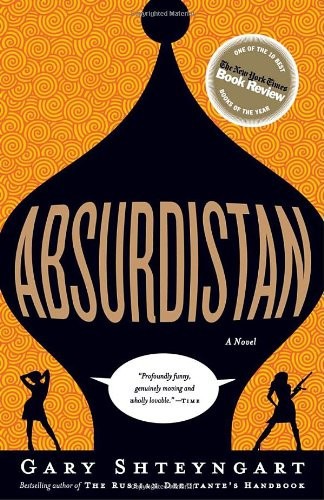

Absurdistan

Authors: Gary Shteyngart

Contents

6 Beloved Papa Is Lowered into the Ground

8 Only Therapy Can Save Vainberg Now

9 One Day in the Life of Misha Borisovich

11 Lyuba Vainberg Invites Me to Tea

13 Misha the Bear Takes to the Air

17 King Leopold’s Belgian Congo

21 The School of Gentle Persuasion

24 Why the Sevo and Svanï Don’t Get Along

30 A Sophisticate and a Melancholic No Longer

32 The Commissar of Multicultural Affairs

38 My Mother Will Be Your Mother

PROLOGUE

Where I’m Calling From

This is a book about love. The next 338 pages are dedicated with that cloying Russian affection that passes for real warmth to my Beloved Papa, to the city of New York, to my sweet impoverished girlfriend in the South Bronx, and to the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS).

This is also a book about

too much

love. It’s a book about being had. Let me say that right away:

I’ve been had.

They used me. Took advantage of me. Sized me up. Knew right away that they had their man. If “man” is the right word.

Maybe this whole being-had deal is genetic. I’m thinking of my grandmother here. An ardent Stalinist and faithful contributor to Leningrad

Pravda

until Alzheimer’s took what was left of her senses, she penned the famous allegory of Stalin the Mountain Eagle swooping down the valley to pick off three imperialist badgers representing Britain, America, and France, their measly bodies torn to shreds in the grasp of the generalissimo’s bloody talons. There’s a picture of me as an infant crawling over Grandma’s lap. I’m drooling on her. She’s drooling on me. The year is 1972, and we both look absolutely demented. Well, look at me now, Grandma. Look at my missing teeth and dented lower stomach; look at what they did to my heart, that bruised kilogram of fat hanging off my breastbone. When it comes to being torn to shreds in the twenty-first century, I am the fourth badger.

I’m writing this from Davidovo, a small village populated entirely by the so-called Mountain Jews near the northern frontier of the former Soviet republic of Absurdsvanï. Ah, the Mountain Jews. In their hilly isolation and single-minded devotion to clan and Yahweh, they seem to me

prehistoric,

premammalian even, like some clever miniature dinosaur that once schlepped across the earth, the

Haimosaurus rex.

It’s early September. The sky is an unwavering blue, its blankness and infinity reminding me, for some reason, that we are on a small round planet inching its way through a terrifying void. Roosting atop the ample redbrick manses, the village’s satellite dishes point toward the surrounding mountains, whose peaks are crowned with alpine white. Soft late-summer breezes minister to my wounds, and even the occasional stray dog wandering down the street harbors a satiated, peaceable demeanor, as if tomorrow it will emigrate to Switzerland.

The villagers have gathered around me, the dried-out senior citizens, the oily teenagers, the heavy local gangsters with Soviet prison tattoos on their fingers (former friends of my Beloved Papa), even the confused one-eyed octogenarian rabbi who is now crying on my shoulder, whispering in his bad Russian about what an honor it is to have an important Jew like me in his village, how he would like to feed me spinach pancakes and roasted lamb, find me a good local wife who would go down on me, pump up my stomach like a beach ball in need of air.

I’m a deeply secular Jew who finds no comfort in either nationalism or religion. But I can’t help feeling comfortable among this strange offshoot of my race. The Mountain Jews coddle and cosset me; their hospitality is overwhelming; their spinach is succulent and soaks up their garlic and freshly churned butter.

And yet I yearn to take to the air.

To soar across the globe.

To land at the corner of 173rd Street and Vyse, where she is waiting for me.

My Park Avenue psychoanalyst, Dr. Levine, has almost disabused me of the idea that I can fly. “Let’s keep our feet on the ground,” he likes to say. “Let’s stick to what’s actually possible.” Wise words, Doctor, but maybe you’re not quite hearing me.

I don’t think I can fly like a graceful bird or like a rich American superhero. I think I can fly the way I do everything else—in fits and starts, with gravity constantly trying to thrash me against the narrow black band of the horizon, with sharp rocks scraping against my tits and stomachs, with rivers filling my mouth with mossy water and deserts plying my pockets with sand, with every hard-won ascent brokered by the possibility of a sharp fall into nothingness. I’m doing it now, Doctor. I’m soaring away from the ancient rabbi clinging warmly to the collar of my tracksuit, over the village’s leafy vegetables and preroasted lambs, over the green-dappled overhang of two colliding mountain ranges that keep the prehistoric Mountain Jews safe from the distressing Moslems and Christians around them, over flattened Chechnya and pockmarked Sarajevo, over hydroelectric dams and the empty spirit world, over Europe, that gorgeous polis on the hill, a blue starry flag atop its fortress walls, over the frozen deadly calm of the Atlantic which would like nothing better than to drown me once and for all, over and over and over and finally toward and toward and toward, toward the tip of the slender island…

I am flying northward toward the woman of my dreams. I’m staying close to the ground, just like you said, Doctor. I’m trying to make out individual shapes and places. I’m trying to piece my life together. Now I can spot the Pakistani place on Church Street where I cleaned out the entire kitchen, drowning myself in ginger and sour mangoes, spicy lentils and cauliflower, as the gathered taxi drivers cheered me along, broadcasting news of my gluttony to their relatives in Lahore. Now I am over the little skyline that has gathered to the east of Madison Park, the kilometer-high replica of St. Mark’s Campanile in Venice, the golden tip of the New York Life Building, these stone symphonies, these modernist arrangements the Americans must have carved out from rocks the size of moons, these last stabs at godless immortality. Now I am above the clinic on Twenty-fourth Street, where a social worker once told me I had tested negative for HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, forcing me into the bathroom to cry guiltily over the skinny, beautiful boys whose scared glances I had deflected in the waiting room. Now I am over the dense greenery of Central Park, tracing the shadows cast by young matrons walking their bite-sized Oriental dogs toward the communal redemption of the Great Lawn. The murky Harlem River flies past me; I skirt the silvery top of the slowly chugging IRT train and continue northeast, my body tired and limp, begging for ground fall.

I am over the South Bronx now, no longer sure if I am soaring or hitting the tarmac at Olympic speed. My girlfriend’s world reaches out and envelops me. I am privy to the relentless truths of Tremont Avenue—where, according to the graceful loop of graffito,

BEBO

always

LOVES LARA

, where the neon storefront of Brave Fried Chicken begs me to sample its greasy-sweet aromas, where the Adonai Beauty Salon threatens to take my limp curly hairdo and turn it upward, set it aflame like Liberty’s orange torch.

I pass like a fat beam of light through dollar stores selling T-shirts from the eighties and fake Rocawear sweatpants, through the brown hulks of housing projects warning

OPERATION CLEAN HALLS

and

TRESPASSERS SUBJECT TO ARREST

, over the heads of boys in gang bandannas and hairnets jousting with one another astride their monster bikes, over the three-year-old Dominican girls in tank tops and fake diamond earrings, over the tidy front yard where the weeping brown Virgin is perpetually stroking the rosary round her blushing neck.

On the corner of 173rd Street and Vyse Avenue, on a brick housing-project stoop riddled with stray cheese puffs and red licorice sticks, my girl has draped her naked lap with Hunter College textbooks. I plow straight into the bounty of her caramelized summertime breasts, both covered by a tight yellow tee that informs me in chunky uppercase script that

G IS FOR GANGSTA

. And as I cover her with kisses, as the sweat of my transatlantic flight soaks her in my own brand of salt and molasses, I am struck stupid by my love for her and my grief for nearly everything else. Grief for my Beloved Papa, the real “gangsta” in my life. Grief for Russia, the distant land of my birth, and for Absurdistan, where the calendar will never pass the second week of September 2001.

This is a book about love. But it’s also a book about geography. The South Bronx may be low on signage, but everywhere I look, I see the helpful arrows declaring

YOU ARE HERE

.

I

Am

Here.

I Am Here next to the woman I love. The city rushes out to locate and affirm me.

How can I be so fortunate?

Sometimes I can’t believe that I am still alive.

1