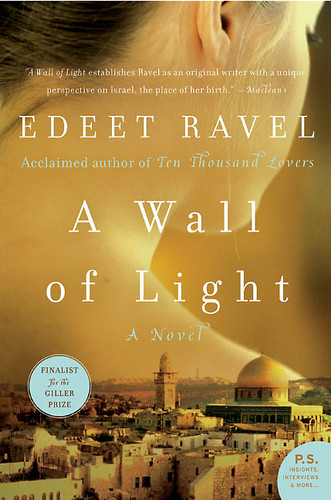

A Wall of Light

Authors: Edeet Ravel

Praise for

A Wall of Light

“Like the great Israeli novelist Amos Oz, Ravel employs the contemporary family unit—a group of disparate people thrown together by genetics or happenstance, loyal to one another despite their differences, and planning for a shared future they can’t predict—as the ideal metaphor for the Jewish state.… She recognizes the cynicism and anger felt by those who have suffered, and her valuable novel offers the simple wish that they will feel love, too—for each other and for life itself.”

—

The Globe and Mail

“Ravel is a master of conserving detail and uses it in an almost painterly fashion, while leaving us with the sense of a mystery unraveling teasingly before us.… Ravel’s Vronskys are always determined in their apparently insensible decision-making. What makes them appealing is Ravel’s skill for portraying a sense of universality.”

—Jewish Independent

“In

A Wall of Light

Edeet Ravel gives us a fascinating, beautifully textured portrait of Israeli society at three stages of its history as seen through the eyes of three characters. The unifying strand is one day in the life of Sonya, who by nightfall has journeyed to the heart of Jerusalem and to the core of her own being. Ravel writes about human complexity with disarming ease. By probing into every corner of her characters’ lives—sexual, emotional, political—she creates a world of deep and refreshing intimacy that replaces barriers with a wall of light. Her style is immediate, honest, subtle. Her language is effortless. Every page brims with life.”

—2005 Scotiabank Giller citation

“Skilfully juggling the weight of the multi-layered past with the bright intensity of the present, Ravel has written a book that shimmers with suspense, mystery and wit. Tell your friends.”

—

Toronto Star

“Like its predecessors, this concluding volume focuses on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and the toll it takes on human lives and especially on relationships. Here, however, the three narrators weave the story together most effectively, showing that while war is a destructive force, love is powerful as well. Ravel writes poignantly about survival and hope in the midst of tragedy. Recommended for all libraries.”

—

Library Journal

ALSO BY EDEET RAVEL

Look for Me

Ten Thousand Lovers

for Fred Harrison

life artist

life artist

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful for the assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $20.3 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada. For their help and support in the writing and publication of the Tel Aviv trilogy, of which this is the final volume, I am deeply indebted to Meir Amor, Yudit Avi-dor, Yardena Avi-dor, Miki Bitton, Alison Brackenbury, Alison Callahan, Nada and Jihad Charif, Marwan Charif, Anne Collins, Pam Comeau, Richard Cooper, Jay Eidemiller, Rezeq Faraj, Rachel Goodman, Mary Harsany, Christopher Hazou, Eric Hamovitch, Michael Heyward, Malcolm Imrie, Matan Kaminer, Ruttie Kanner, Yitzhak Laor, Shimon Levy, Kfir Madjar, Mark Marshall, Michael MacKenzie, Rachella Mizrahi, Moshe, Adrienne Phillips, Ken Sparling, Gila Svirsky, Yafa Wax, Claire Williamson, Margaret Wolfson, Miriam Zehavi, the Headline crew, the staff of the Metropolitan Hotel in Tel Aviv, and the many fellow activists who have given me the strength to maintain hope in the midst of tragedy. Filling my life with fun and love, my daughter Larissa continues to inspire and enchant me.

All losses are restored,

and sorrows end.

—Sonnet 30, Shakespeare

S

S

ONYA

I

am Sonya Vronsky, professor of mathematics at Tel Aviv University, and this is the story of a day in late August. On this remarkable day I kissed a student, pursued a lover, found my father, and left my brother.

The morning began with a series of sneezes. The sneezes interrupted a dream I was having about a glass-walled elevator that had left its shaft and was shooting about wildly through immense futuristic building complexes. Like something out of Asimov, I thought. I was just starting to enjoy both the sensation and the spectacle when the sneezes woke me.

I like to sleep with the shutters open; I like to feel the sun on my body as soon as I wake. A warm, luminous world awaits me—or so I imagine. Ordinarily, I would have switched off the air-conditioning, opened the window and looked out at our garden; I would have turned my face toward the sky and breathed in the sweet, tyrannous August air. But today my sneezing distracted me. My late-summer allergies were kicking in.

I sat up in my queen-sized bed and reached for the box of rainbow-colored tissues on the night table. I set the box between my knees, which were protruding like two islands from under the sheets. A boxy ship, precariously balanced.

My mother, who slept next to me when I was little, always accompanied her good-night kiss with a quote—affectionate if she was sober (“Come, live with me, and be my love,” for example), gloomier if she was inebriated (“Out, out, brief candle!”). Then she’d turn off the light and I’d snuggle up against her lace nightgown, breathe in her cinnamon perfume. My mother was a night bird; when she woke she was not in a quoting mood. But I am the opposite, more inclined toward poetry in the morning than at bedtime, and I suppose my choices are also somewhat less formal than hers. “You are old, Father William …,” I began, but didn’t finish; a sneeze interrupted me.

Kostya, my darling brother, appeared in the doorway, dark and shadowy because the light was behind him. With his trimmed gray beard and his tall, still body he looked like a character in a French film from the 1960s, a film about alienation and ennui, with the male lead dark and brooding. In fact, he was there to offer me an antihistamine. My brother has very low tolerance for disruption, and the sneezes were annoying him.

But I’m being unfair: he was also trying to help. My poor brother lives with the guilt of my two catastrophes, neither of which he had anything to do with. Human error lay behind the first disaster: twenty years ago, when I was twelve, I was taken to the hospital with a kidney infection, and some nurse or doctor or hospital pharmacist gave me the wrong dose of the wrong drug. I moved into another dimension, spooky at first, frightening at first, then surreal, and finally exotic or ridiculous, depending on the day. I lost my hearing.

And human evil, which no one can entirely avoid, accounts for the artillery unleashed at me in an empty university classroom by stoned twin teenagers with shaven heads and dragon tattoos.

But guilt has a way of insinuating itself into the path of any series of events leading to a given outcome. Kostya believes, for example, that had he fixed our broken toilet, I would not have come down with a kidney infection in the first place. The toilet howled and groaned like a ghoul in chains and I was afraid to use it; my solution was to drink less in order to limit my visits to the bathroom. I didn’t tell anyone about my aversion; had Kostya known, he would have attended to the problem. And then, had I not been deaf I might have heard the twins before seeing them (this is really stretching it) and escaped in time. These are tenuous links but well entrenched in our family mythology.

“Do you want an allergy pill?” my brother asked, speaking as he signed. “It’s non-soporific.” We’d developed so many signing shortcuts and private gestures over the years that by now we almost had our own language.

“Oh … kay!” I managed to say between sneezes. He vanished and returned with a small yellow pill, his heartbreaking offering of the morning, nestled in the palm of his large, intelligent hand. In his other hand he held a small bottle of Eden spring water.

I obediently swallowed the pill. “You’re lucky I’m so nice to you,” I said.

My brother smiled. It would be no exaggeration to say that he suffers from my misfortunes more than I ever did. He should take comfort in the fact that I have a good life, that I have fun—and maybe he does, to some degree. Maybe not. It’s hard to know for sure.

“Tell me when you’re ready for breakfast,” he said.

I blew him a kiss and he left the room. My briefcase was next to the night table, and I emptied its contents in front of me. Exams, articles, receipts, notes and miscellaneous slips of paper floated out angelically and settled on the bed. I organized them all efficiently and quickly. Then I waddled to the bathroom like a goose headed for its mud pond, and had a shower. There is nothing quite as wonderful and endlessly surprising as a soft, heavy stream of hot water falling on one’s shoulders and down one’s body. I was filled with gratitude, as I always am during the first few moments of a shower, that something so lovely exists on this planet, and I was only sorry that it was not available to everyone. A few kilometers away, there was not even enough drinking water.

But, inexcusably, my sense of guilt soon faded, and as I ran the soapy sea sponge along my legs I succumbed completely to the pleasures of my morning shower.