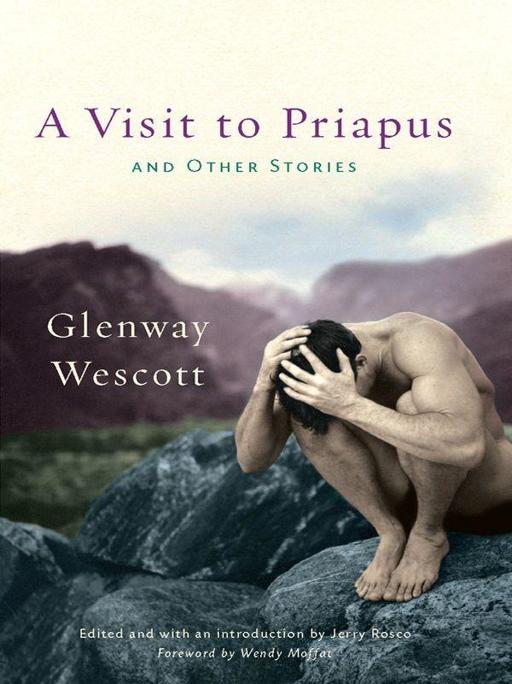

A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories

Read A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories Online

Authors: Glenway Wescott

OOKS BY

G

LENWAY

W

ESCOTT

Novels

The Apple of the Eye

The Grandmothers

The Pilgrim Hawk

Apartment in Athens

Stories

Goodbye, Wisconsin

A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories

Essays

Fear and Trembling

Images of Truth

Journals

Continual Lessons

A Heaven of Words

Poetry

The Bitterns

Natives of Rock

Other

A Calendar of Saints for Unbelievers

Twelve Fables of Aesop Newly Narrated

A Visit to Priapus

AND

O

THER

S

TORIES

Glenway Wescott

Edited

and with an introduction

by

Jerry Rosco

The University of Wisconsin Press

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Published by arrangement with the Estate of Glenway Wescott,

Anatole Pohorilenko, literary executor, c/o Harold Ober Associates Incorporated

Compilation and new matter copyright © 2013 by Anatole Pohorilenko

Introduction and editorial notes copyright © 2013 by Jerry Rosco

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wescott, Glenway, 1901-1987, author.

[Short stories. Selections]

A visit to Priapus and other stories / Glenway Wescott; edited and

with an introduction by Jerry Rosco.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-299-29690-2 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-29693-3 (e-book)

I. Rosco, Jerry, editor. II. Title.

PS3545.E827V57 2013

81352—dc23

2013010427

“The Stallions,” “An Example of Suicide,” and “Sacre de Printemps” are previously unpublished. “Adolescence” was first published in

Goodbye, Wisconsin,

copyright © 1928, 1955 by Glenway Wescott. “A Visit to Priapus” was first published in

The New Penguin Book of Gay Short Stories,

copyright © 2003 by Anatole Pohorilenko. “The Odor of Rosemary” was first published in

Prose

(Spring 1971), copyright © 1971 by Glenway Wescott. “The Valley Submerged” was first published in

The Southern Review

(Summer 1965), copyright © 1965 by Glenway Wescott. “The Babe’s Bed” was first published by Harrison of Paris (1930). “Mr. Auerbach in Paris” (April 1942) and “The Frenchman Six Feet Three” (July 1942) were first published in

Harper’s.

“The Love of New York” was first published in

Harper’s Bazaar

(December 1943). “A Call on Colette and Goudeket” was first published in

Town and Country

(January 1953).

A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories

The Stallions:

Pages from an Unfinished Story

A

PPENDIX

: T

WO

E

SSAYS AND AN

E

XPERIMENTAL

S

TORY

A Call on Colette and Goudeket

W

ENDY

M

OFFAT

The British novelist E. M. Forster would be posthumously delighted that these stories by Glenway Wescott have found a public audience. “A Visit to Priapus” now joins Forster’s

The Life to Come and Other Stories

and

Maurice,

worthy writing on gay themes that was suppressed for decades as “the penalty society exacts” for its hatred and fear of homosexuals. The publication of these stories by Wescott marks a “happier year.”

1

Wescott revered Forster the man, his art, and his powerful humanistic vision. His novels, including

A Room with a View

,

Howards End,

and

A Passage to India

had established him internationally as a great man of letters. Wescott and Forster met in the 1940s at an auspicious time for both men. Forster, almost seventy, finally felt free to live a more open life after his mother’s death. Wescott, a generation younger, was a relentlessly exacting writer whose early celebrity had somewhat faded. But the renewed critical success of

The Pilgrim Hawk

(1940) encouraged Wescott. He had begun to write the searingly honest stories in this collection.

To Wescott, Forster was a cross between a

paterfamilias

and a patron saint of gay writing. The myth that the old man had written a gay love story with a happy ending, written it decades before, even before World War I, circulated seductively among Wescott’s New York friends. In 1949 Wescott parlayed a decade of correspondence into an invitation for Forster to visit the United States. To Wescott’s delight Forster brought along his partner, the policeman Bob Buckingham. The couple spent a weekend at Wescott’s country house and enjoyed a notably ribald and frank dinner party in the company of Wescott, his partner Monroe Wheeler, and the sexologist Dr. Alfred Kinsey.

During Forster’s visit, Wescott learned the whole story of the writing and suppression of

Maurice

. Like Wescott, Forster had felt isolated and tormented by his homosexuality. He began the novel in 1913 under the benign influence of a gay mentor a generation older than he. Forster made a pilgrimage to the Victorian sexual radical Edward Carpenter and his working-class partner Edward Merrill, approaching the older man “as one approaches a saviour.”

But Merrill had more corporeal ideas. He made a pass at the young and timid Forster—“touched my backside—gently and just above the buttocks,” Forster wrote wryly decades later. “The sensation was unusual and I still remember it, as I remember the position of a long vanished tooth. It was as much psychological as physical. It seemed to go straight through the small of my back into my ideas … I then returned to where my mother was taking a [rest] cure, and immediately began to write

Maurice”

2

Forster tinkered with the novel for decades. He found excuse after excuse not to publish—first to protect his mother’s feelings, then to protect Bob’s. He decided finally that posthumous publication would be best. So the reading public discovered

Maurice

in 1971, two years after the Stonewall riots. But in its long unpublished private life

Maurice

became a talisman of gay friendship, a secret passed from hand to hand among a circle of intimates whom Forster trusted. Wescott was delighted to be among them.

We cannot know whether Forster understood how deeply Wescott identified with Forster and the

hegira

of writing

Maurice.

The psychological and stylistic similarities between Wescott and his mentor are striking. Like Wescott and his narrator Alwyn Tower in “A Visit to Priapus,” Forster’s “self-consciousness is extraordinary.”

3

His sensitivity opened him to a subtle inner world—and occasionally it paralyzed his creativity. In his gay fiction, like Wescott, Forster grapples with the intricacy of intimacy, both the poisonous distortions and the creative complexity of the closet.

Wescott too agonized over his story, and refused to publish it during his lifetime. But it is a mistake merely to conflate the value of Wescott’s story with the tortured circumstances of its creation. This almost- novella is a wonderful story, “an intellectual effort, a moral embrace.”

4

“A Visit to Priapus” is a meditation on desire and art, a rueful, comic, brutally honest consideration of sex and its human limitations.

Wendy Moffat is the author of the prize-winning

A Great Unrecorded History: A New Life of E. M. Forster

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010). She is a professor of English at Dickinson College.

1

E. M. Forster, “Notes on

Maurice

,” in

Maurice,

ed. Philip Gardner (London: Andre Deutsch, 1999), 216. “To a happier year” is Forster’s dedicatory phrase for the novel. Forster’s “Notes” were written in 1960.

2

Ibid., 215.

3

Glenway Wescott,

A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories,

50.

4

Ibid., 71.

Dedication to any literary work requires some sort of inspiration and encouragement because, almost always, there are obstacles, deflating discouragements, and dark days along the way. After editing Glenway Wescott’s journals and stories, and researching and writing his biography, I have to acknowledge the man himself. No one ever loved literature and language more. Both Marianne Moore and Katherine Anne Porter scolded him for dedicating himself so often to the work of others. Likewise, literary editor Robert Phelps helped the elderly Wescott overcome the doubts and regrets that often haunted him. Another key figure is Anatole Pohorilenko, a faithful and thoughtful executor.

One must acknowledge the role of our great libraries in helping us put the artist’s work and personal story in perspective. I am grateful to curator Timothy Young and the staff of the Beinecke Library at Yale. Thanks also to the staff of the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library.

Fate plays a role in which publisher brings a book to its readers. My thanks to acquisition editor Raphael Kadushin for his savvy decision- making, instincts, and experience. And the entire effort at the University of Wisconsin Press—editorial, production, marketing, art, and events planning—is like a throwback to the golden age of book publishing. Thanks to all.

Special thanks for great advice to three writers: San Francisco’s Kevin Bentley, Toronto’s Ian Young, and Wisconsin’s Richard Quinney.

As Wescott readers old and new know, the spirit of Glenway dedicates this book to Monroe Wheeler.

Glenway Wescott was a perfectionist, and that quality was both a key to his talent—as a poet turned exacting prose writer—and a handicap, because he often had trouble finishing his work. Yet what he did finish holds up: novels, stories, essays, plus two books of posthumous journals revealing a life rich in literature, art, and famous friendships. But perhaps one more work—this group of previously uncollected stories—can reveal even more about Wescott himself. The title story, unpublished in his lifetime, was called “a posthumous masterpiece” by Ned Rorem in his diaries. “A Visit to Priapus” is a long story written in 1938 about a gay liaison. Like E. M. Forster’s novel

Maurice

, it was considered unpublishable at the time and for many decades afterward. Now it appears here, surrounded by other autobiographical stories—several also never previously published. Together they form a truthful, chronological portrait of the author.

For those unfamiliar with the author, Glenway Wescott (1901-87) went from living on a poor Wisconsin farm to accepting a University of Chicago scholarship when he was only sixteen, but his education was cut short after three semesters by a near-fatal case of the Spanish Flu. Still, he became known among the Imagist poets, and his lyrical novel of Wisconsin,

The Apple of the Eye

(1924), was very well received. His lifelong partner, Monroe Wheeler, convinced Wescott to move first to New York, then to France to live among the expatriates. There he achieved fame with

The Grandmothers

(1927), a best-selling chronicle-style novel of the Midwest. His Midwestern fiction ended with a book of stories,

Goodbye, Wisconsin

(1928), and a deluxe encased story, “The Babe’s Bed” (1930). A book of prewar essays,

Fear and Trembling

(1932), missed its mark (prophetic but too indirect and elegant), and

A Calendar of Saints for Unbelievers

the same year was witty and comical but a small work.

Back in America in the 1930s, Wescott was frustrated after two abandoned novels. Meanwhile, Monroe Wheeler began his long career as director of publications and (later) exhibitions at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and their co-resident companion, George Platt Lynes, soon made his name as a photographer. However, by 1938 Wescott found his narrative voice with several stories, including “Priapus.” He would not publish that story in his lifetime, but it led directly to perhaps his greatest achievement, the novella

The Pilgrim Hawk

(1940)—“among the treasures of twentieth-century American literature,” wrote Susan Sontag. There would be a Book-of-the-Month-Club best seller set in World War II,

Apartment in Athens

(1945), as well as a few more abandoned novels. After that, Wescott turned to essays—including the volume

Images of Truth

(1962)—reviews, and his journals. Because his brother Lloyd married the heiress and art patron Barbara Harrison (they appear under fictitious names in two stories in this collection), Glenway had a home on their western New Jersey farm, in addition to Monroe Wheeler’s city apartment. While he had two best sellers during his long life, he mostly lived a comfortable but near penniless life, “a bird in a golden cage,” as he said.