A Trip to the Beach (28 page)

The noise from the wind was deafening, and as it began to get darker outside, Bob knew it was going to be a long night.

The storm must be half over,

he thought. He had no radio and no way of judging where the eye of the hurricane was. He knew that once the eye passed over, it would be halfway through. He also knew that the winds on the front side of the eye travel in one direction and on the back side they go the other way. So far nothing was coming into the balcony, only flying past it, so the sliding doors were not yet threatened. But if the wind shifted around, the thought of broken boat masts, palm trees, or sheets of metal roofing crashing into his room began to scare Bob.

He decided to drag the mattress into the bathroom and cover the tub with it as a precaution. If the doors blew in, he would run for cover. In the meantime, he lay on the couch.

The full force of the storm was pounding against the back door to Bob's room, which opened onto a long, narrow walkway. He hadn't even thought about that door before, because it was made of steel and set into a concrete wall. The pressure against it, however, was incredibly strong, and around the edge of the door a spray of water forced its way into the room and shot in three feet toward the bed. It looked as if the wall had sprung a leak. There was also a stream of water entering through the tiny hole in the wall that carried the phone line. This stream was about an eighth of an inch in diameter, and it too shot out three feet into the room. Bob put his finger over it for a second, feeling like the little Dutch boy plugging the hole in the dike.

He tried to think of what he could use for a plug. A box of toothpicks might work, but there were none. He decided to use some of his wooden matches but broke them in half first, saving the good ends just in case the candles went out. Using the flat end of a knife to push with, Bob jammed several of the match ends into the hole, trying not to damage the phone line in the event phone service was restored the next day. He succeeded in reducing the stream of water to a fine spray, then turned his attention to the door.

Using the knife to force a sheet from the bed into the crack around the door, Bob was able to stop most of the water from spewing into the room. He jammed a towel under the door and used another to mop up the water, wringing it out in the bathroom sink.

Debris pummeled the back door as the storm howled outside. The door was made of steel, but what would happen if some heavy flying object hit it hard enough? Bob doubted it could withstand a boat mast traveling at 150 mph.

He decided to open a can of cheese curls. Sitting down on the couch in the candlelight, he listened to the roar of the wind and wished he were with me watching it all on television.

The night seemed to last forever. After a second can of cheese curls, Bob started to doze, but every five or ten minutes something would hit the steel door and wake him up. Each time he would jump to see if the wind was shifting to the sliding glass doors, but it seemed to be staying the same.

Where is the eye?

he wondered. Maybe St. Martin wasn't in the center of the storm after all and there wouldn't be an eye. If that was true, then it could be almost over. It had been eighteen hours since it started, and it was getting light outside.

The sky in Maine the next morning was clear and blue, and Pat and I felt disoriented by the beautiful sunshine. It was surreal to talk about nothing but the storm and see nothing but blue sky above. We walked across the street and had blueberry pancakes and talked about how long it would be before we heard from Bob.

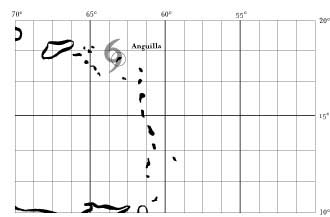

SEPTEMBER 6â8 a.m. TROPICAL UPDATE

Location: 64.00 WÂ Â Â Â Â Â 19.20 N

Sustained winds 145 mph

Gusts up to 185 mph

Category 4 hurricane

Moving 7 mph WNW

Location 90 miles NW of Anguilla

Bob got up and pressed his hand against the sliding door. He could feel the glass flex in and out as the pressure outside changed with the wind. He cracked it open, and it was as if the wind was fighting to yank the door from its frame. He stepped hesitantly onto the balcony. The walls outside were covered with sand; leaves and palm fronds were plastered against them, as if with glue. The wind showed no signs of letting up, and it was still too dark to see much through the rain.

Not having any idea how much longer the storm would continue, Bob went back to reading by candlelight, which in a matter of minutes lulled him to sleep. He woke up around ten and cracked open the door again. The wind seemed to be letting up a little, and the rain was lighter. Bob noticed that all but one of the seven boats tied to the pier in front of his room had sunk during the nightâthe sailboat masts and cabins of the motor yachts protruded from the water. It was doubtful they could be salvaged. He spotted a group of teenagers across the harbor walking along a chain-link fence that separated Port de Plaisance from the vacant lot next door. They clung to the fence in the wind and made their way slowly toward the main building.

What are they doing out in this storm?

Bob wondered. Either they were seeking shelter because their house had been destroyed, or they were up to no good. It became clear that they were not seeking shelter as one of them climbed the fence, jumped to the other side, and made his way to the Port de Plaisance storeroom. A second boy followed over the fence and boosted the first one up to a hole in the concrete wall where there had been a window the day before. After some scrambling, the first kid disappeared inside and soon began passing bottles of liquor through the hole, where they were carefully packed into backpacks. Once the packs were full, the group continued to empty the storeroom, making a pile of loot on the other side of the fence. There was enough contraband to warrant a second and possibly even a third trip to remove it all.

One of the boys climbed back out of the window and dropped to the ground, but rather than scale the fence again, he decided to go down to the pier and see what else he could find. He lunged from one piling to another, hanging on to the posts during the gusts of wind. He climbed into the cabin window of one of the half-sunken yachts and thirty seconds later emerged with what appeared to be a radio. He made his way back to the others, climbed the fence, and ran.

Documenting the entire event through his zoom lens, Bob found it amazing that the storm wasn't even over yet and looting had already begun.

John Hope reported that after a day and a half of hammering the islands of Anguilla and St. Martin, Hurricane Luis was finally moving on. He had no word of specific damage, but the worst was definitely over. I had told Bob we'd be back in Vermont waiting for news after the storm was over, so Pat and I drove home that afternoon. We sat in the living room, still glued to CNN and the Weather Channel, hoping to hear some bit of news about Anguilla or St. Martin. As initial reports trickled in, I imagined the worst.

By two o'clock, the wind had calmed even more, and Bob desperately needed to get out of the room. He unlocked the back door, removed the waterlogged sheet from around the jamb, and opened the door for the first time in nearly thirty hours. He stared in disbelief at the devastation. Lush landscaping had been reduced to rubble, with not a green leaf or a palm frond in sight. All of the trees had either been snapped off near the top, leaving what looked like a telephone pole, or had been uprooted. The poolside bar was simply gone. The furniture in the pool appeared still to be there, but it was hard to tell because the crystal clear water from the day before was black and filled with leaves, branches, and awning material from the bar.

Bob climbed over tree limbs and broken boards that had been blown against the back of the building. As he made his way down to the main level, his first thought was to get to a phone and let me know he was okay. He went around the corner of the building and saw two men turning toward the shore. He followed them and watched in shock as they pulled a man out from under some debris. Before he knew it, Bob was helping to carry this battered man back over to the hotel, where they stretched him out on a couch in the room where the buffet had been.

The man's head had a terrible gash, and he was babbling in French. He looked like Robinson Crusoe, with a long furry beard, leathery skin, long silver hair, and only a pair of boxer shorts on. A small crowd had now gathered around as more and more guests ventured out of their rooms. A short fat man came around the corner announcing he was a doctor, and everyone moved out of his way.

“Mr. Spittle,” the rotund doctor said, “I will need a needle and thread to sew up this cut.” The Frenchman was wailing as Mr. Spittle returned with a sewing kit from the laundry. One of the other guests was interpreting, and trying to explain to the injured man that a doctor was going to stitch up his head. Mr. Spittle had produced a first-aid kit, and after the doctor sterilized the needle and thread with some brown liquid, he sewed up the gash in front of the crowd. The old man screamed; Mr. Spittle held his head, and Bob and several other guests held his arms and feet. His head was then bandaged, and he sat up and stared at everyone in disbelief.

The interpreter translated his story, and Bob and everyone else listened as the man described the events of the previous night. He had been living on his catamaran, sailing around the islands for years, and had come to St. Martin to weather the storm in a safe harbor. During the night he felt his boat being lifted out of the water and found himself flying through the air and thrown against the shore. His catamaran was completely demolished, and he was pinned under a section of the hull with water up to his neck.

He spent the night trapped under the debris, hoping the hull wouldn't shift and drown him. When the storm finally died down, he started to yell, and the two guests had heard him and dragged him out from under the remains of his boat. He was lucky to be alive. He also said that his radio was going all night and he listened to people pleading for help as their boats sank.

Bob was beginning to realize the magnitude of the disaster. Sunken boats were everywhere. An unimaginable number of masts stuck up out of the water. Down in the far corner toward the airport, a pile of boats lay tangled and destroyed beyond belief. Hundreds of motor yachts, sailboats, and barges were heaped on top of each other in a tangle of ropes, masts, broken glass, hulls, sterns, and keels.

He had to call home. He imagined pictures of the devastation on CNN and knew I would be frantic with worry. All the lines were down at the hotel, and Bob thought maybe he should start walking to Marigot to look for a phone. As he headed out the long, winding entrance to Port de Plaisance, stepping over branches and other debris, a car pulled up behind him. “Need a lift?” a man asked.

“Where are you going?”

“I know where there's a phone,” the man said. “I'm going to call my wife and tell her I'm alive.” It was as if he had read Bob's mind.

“Great,” Bob said as he climbed into the backseat.

There was a man in the front passenger seat talking on a two-way radio. Bob couldn't help but notice they were wearing dark suits, unusual attire for the islands.

“Are you policemen?” Bob asked after listening to a little of the radio conversation. It was clear that the storm had disrupted something they had been working on and that the chances of resuming their project were not good.

“We work for the DEA,” the driver said. “We've been coordinating a drug bust here for two months with Scotland Yard, the French police, and the Dutch police out of Curaçao. This damned storm screwed everything up.”

“So how do you know about a phone?”

“Some of our men are staying at another hotel, and they told us by radio this morning that there's a USA Direct phone in the lobby that still works for some reason. Here it is now.” The car pulled into a parking lot in front of the Atrium Hotel near the airport.

Inside the lobby there was a tremendous crowd waiting to use the phone. Bob stood behind the driver of the car and waited patiently for his turn; the line was long but moving quickly. The woman behind the front desk was collecting a dollar a minute for the use of the phone in addition to the charges put on everyone's calling card. She had a thriving business going.

John Hope, by now my arbiter of all matters of importance, said phones and power would be out for an extended period of time, so I knew we wouldn't be hearing from Bob right away. Pat and I went out for pizza, and when we returned home, we were surprised that Bob had left a message on the answering machine.

“Hi, it's me. I'm alive and well in St. Martin. I'm fine, but there's mass destruction everywhere. Don't worry about me; just worry about the restaurant. I'm going to try to get to Anguilla now. Bye.”

I called Jesse right away and we talked for an hour about how relieved we were. Jesse was anxious to speak with Bob directly and made me promise to let him know when I received more information.

As Bob hung up the phone he looked around for his newfound friends, the DEA agents. They were nowhere in sight. Bob walked back outside and spotted the car. Knowing the men were in the hotel somewhere, he sat on the railing of the parking lot and waited. After almost half an hour he went back inside and walked up to the counter, where the girl was continuing to collect her dollar per call. The line was still about twenty people long as each person reported in to their loved ones. Bob asked if the girl had seen two men in dark suits with a two-way radio. She said, “A whole bunch a them on three.”