A Tragic Legacy: How a Good vs. Evil Mentality Destroyed the Bush Presidency (14 page)

Read A Tragic Legacy: How a Good vs. Evil Mentality Destroyed the Bush Presidency Online

Authors: Glenn Greenwald

Tags: #Government - U.S. Government, #Politics, #United States - Politics and government - 2001- - Decision making, #General, #George W - Ethics, #Biography & Autobiography, #International Relations, #George W - Influence, #United States, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Political Science, #Good and Evil, #Presidents - United States, #History, #Case studies, #George W - Political and social views, #Political leadership, #Current Events, #Political leadership - United States, #Executive Branch, #Character, #Bush, #Good and evil - Political aspects - United States, #United States - 21st Century, #Government, #United States - Politics and government - 2001-2009 - Decision making, #Government - Executive Branch, #Political aspects, #21st Century, #Presidents

Biden said that Bush stood up and put his hand on the senator’s shoulder. “My instincts,” he said. “My instincts.”…

The Delaware senator was, in fact, hearing what Bush’s top deputies—from cabinet members like Paul O’Neill, Christine Todd Whitman and Colin Powell to generals fighting in Iraq—have been told for years when they requested explanations for many of the president’s decisions, policies that often seemed to collide with accepted facts. The president would say that he relied on his “gut” or his “instinct” to guide the ship of state, and then he “prayed over it.”

Precisely the same dynamic drove the president’s approach to the 2006 midterm elections. For several months prior to those elections, virtually every public poll—every one—showed that Republicans were highly likely to lose control of the House. Particularly in the weeks before the election, the only real debate among pollsters and political analysts was how massive the Republican losses would be. Congressional Republicans were petrified at what appeared to be the certain doom approaching. Yet the president was convinced that all the polls were wrong and that Republicans would hold their majority.

All politicians publicly adopt optimistic poses. Candidates who are thirty points behind in polls will claim in the media that they expect to defy the polls and win. Outside of fringe political parties, no candidate can admit to an expectation of losing; such an admission would almost always become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Nobody is going to work to elect a political candidate who himself expects to lose, and in a country that venerates being a winner more than almost any other attribute, a politician who brands himself a likely loser is sure to become one quickly.

But the president was not contriving optimism about the midterms for public consumption. In private he was also emphatically insisting to Congressional Republicans and other trusted confidants that Republican success was assured. On October 15, Michael Abramowitz reported in the

Washington Post:

“Amid widespread panic in the Republican establishment about the coming midterm elections, there are two people whose confidence about GOP prospects strikes even their closest allies as almost inexplicably upbeat: President Bush and his top political adviser, Karl Rove.”

That optimism, apparently based on nothing other than his own belief in his inevitable entitlement to victory, began to worry and even anger members of the president’s own party. On October 13, 2006, Kenneth Walsh reported in

U.S. News World Report:

Some Republican strategists are increasingly upset with what they consider the overconfidence of President Bush and his senior advisers about the midterm elections on November 7—a concern aggravated by the president’s news conference this week.

“They aren’t even planning for if they lose,” says a GOP insider who informally counsels the West Wing. If Democrats win control of the House, as many analysts expect, Republicans predict that Bush’s final two years in office will be marked by multiple congressional investigations and gridlock.

Republican concern over the president’s refusal to accept the evidence of this pending electoral devastation led to multiple press accounts in which prominent members of his party complained of Bush’s apparent detachment from reality. The

Washington Post

’s Dan Froomkin wrote on October 16: “The question is whether this is a case of justified confidence—based on Bush’s and Rove’s electoral record and knowledge of the money, technology and other assets at their command—or of self-delusion. Even many Republicans suspect the latter.” Froomkin added: “The notion that President Bush is not just in denial—but is

petulantly

in denial—is taking on greater credence.”

The election results, of course, vindicated Republican fears that the president had, yet again, simply refused to accept unpleasant facts—i.e., reality—which were in conflict with his faith-based certitude. The day after the election, the president held a press conference and was asked: “You said you were surprised, you didn’t see it coming, you were disappointed in the outcome. Does that indicate that after six years in the Oval Office, you’re out of touch with America for something like this kind of wave to come and you not expect it?”

The president’s reply was instructive: “Well, there was a—I read those same polls, and I believe that—I thought when it was all said and done, the American people would understand the importance of taxes and the importance of security.” In his mind, Republicans lost the election

not

because Bush had embarked upon the wrong path or made the wrong choices—that is something that, by definition, cannot be—but because Americans failed to “understand the importance of taxes and the importance of security.” Americans failed to recognize the Good and that Bush was fighting for it.

That “reasoning” was similar to the explanations issuing from the president prior to the 2006 election as to why he was certain, polls not-withstanding, that Republicans would win. Gigot interviewed the president in September and wrote in the

Wall Street Journal:

ABOARD AIR FORCE ONE—SPEAKER NANCY PELOSI?

“That’s not going to happen,” snaps the president of the United States, leaning across his desk in his airborne office. He had been saying that he hoped to revisit Social Security reform next year, when he “will be able to drain the politics out of the issue,” and I rudely interrupted by noting the polls predicting Ms. Pelosi’s ascension.

“I just don’t believe it,” the president insists. “I believe the Republicans will end up being—running the House and the Senate. And the reason why I believe it is because when our candidates go out and talk about the strength of this economy, people will say their tax cuts worked, their plan worked…. And secondly, that this is a group of people that understand the stakes of the world in which we live and are willing to help this unity government in Iraq succeed for the sake of our children and grandchildren, and that we are steadfast in our belief in the capacity of liberty to bring peace.”

“I just don’t believe it”—it

being the mountains of empirical data showing that Americans would remove his political party from power because of their profound dissatisfaction with his job performance generally, and with the Iraq War specifically. To the president, his decisions are so plainly and indisputably right, his course objectively grounded in what is Good, that it was literally inconceivable to him that Americans opposed his policies and would repudiate his party—notwithstanding massive and compelling evidence that they would. As always, empirical evidence was no match for his certitude.

The compulsion to ignore or deny the credibility of conviction-undermining facts is equally evident in the president’s most mindlessly loyal followers. Hugh Hewitt is an evangelical Bush supporter with a popular talk radio show and blog. He also had the misfortune of writing a book in 2006—the same year, of course, when the Republicans suffered one of their worst electoral defeats in history—entitled

Painting the Map Red: The Fight to Create a Permanent Republican Majority

.

In the three weeks prior to the 2006 midterm election, Hewitt repeatedly insisted that Republican candidates were tied or ahead even when the consensus of polls showed those candidates were actually behind, sometimes by substantial margins. He was not merely predicting that the GOP candidate behind in the polls would win (there is nothing wrong with being hopeful). Rather, he was insisting that the GOP candidates who were behind in the polls were, in fact,

ahead in the polls

.

In response to e-mails he received objecting to his bizarre interpretation of the polling data, he explained his “thinking” behind this outright distortion of reality (emphasis added):

I get a lot of e-mail asking me why I point to polls like the one favoring Steele when I discount some polls favoring some Democrats.

Because this question comes mostly from lefties, I will pause to explain in as uncomplicated a fashion as possible.

Polling methodology and models favors Democrats. So polls that show Republicans tied or ahead I see as indicating a race in which the Republican is in the lead.

Polls that show a Republican within striking distance I see as a poll indicating a dead heat.

It shouldn’t be that hard to grasp, even for a lefty.

In Hewitt’s world, polling data—like all other data, from war zone reports to intelligence assessments and everything in between—can be ignored and disregarded at will when it is unpleasant because it is unfairly biased against the Republicans. Hewitt took the data that he disliked, literally changed it in his own mind to make it more pleasant, and then embraced the fictitious data as his reality.

In fact, polling data for the 2006 midterm elections predicted results in the vast majority of races with almost complete accuracy. In the instances where there was a discrepancy, it was nearly in every case

favorable to the Republicans

—meaning the polling showed Democrats with a smaller lead than they ended up with (or behind by more than they actually lost by).

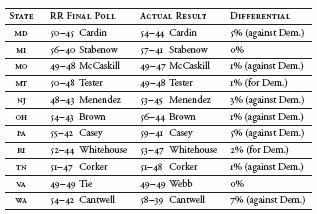

Following is a chart comparing the final polls of Rasmussen Reports for the eleven Senate races it (and the rest of the country) identified as the “Nation’s Closest Senate Races” (Connecticut is the only race excluded here due to its confusing party breakdown). The table shows the final Rasmussen poll for each race, the actual election results, and the differential between the two and indicates whether the differential favored the Republican or the Democratic candidate:

In the eleven Senate races identified as “the closest Senate races” (excluding Connecticut), Rasmussen’s polls predicted the exact outcome in two of them. For the nine races where there was a disparity, seven of the nine disparities

favored the Republicans

. Only two of the eleven races showed a gap in favor of Democrats, and in those two races (Montana and Rhode Island), the difference was minuscule—respectively, 1 percent and 2 percent.

And it was not just Rasmussen. Polls in general were either remarkably accurate or, to the extent they were wrong, largely skewed in favor of Republicans (at least in terms of what they predicted versus the actual result). The Real Clear Politics average final polls (which averaged the outcomes of multiple polls from around the country) show that for the same eleven Senate races, the polling disparities

favored Republicans in eight of the eleven races, often by considerable margins.

In the three races where the disparities favored Democrats, it was by very small margins, of 1 to 3 points.

The point here is not to criticize Hewitt for being wrong in virtually all of his prognostications about the midterm elections. It is natural for partisan desires to influence people’s predictions, and predicting races even within the science of polling, let alone without it, is extremely difficult. But Hewitt was not merely inaccurate. As is so common among Bush supporters (including, as demonstrated above, the president himself), Hewitt ignored, indeed

consciously denied and rejected,

information that undercut his beliefs, and insisted that even the most objective facts were “biased.” As Stephen Colbert put it during his highly controversial, satirical speech at the White House Correspondents Dinner in 2006:

Now, I know there are some polls out there saying this man [the president] has a 32 percent approval rating. But guys like us, we don’t pay attention to the polls. We know that polls are just a collection of statistics that reflect what people are thinking in “reality.” And reality has a well-known liberal bias.

Though it was satire, Colbert’s point captured exactly the manner in which Hewitt argued. And as noted, the president himself repeatedly insisted that the Republicans would win the election despite all of the data to the contrary ( just as he continuously insisted that the United States was making progress and even “winning” in Iraq for years despite abundant evidence negating such a claim). The president, like his zealous supporter Hewitt, was not merely waxing optimistic. Rather, both decided that empirical evidence was meaningless, because it was unpleasant, because it conflicted with their convictions, and

it therefore could not be real.

A

mong the most striking aspects of the Bush administration has been the extent to which loyalty has been demanded of, and received from, those who work near the president. The requisite loyalty is to George Bush the individual (and his decisions). In contrast to prior administrations, the Bush administration has marched in virtual lockstep. Leaks by senior White House officials unfavorable to the president have been almost unheard of, particularly when compared to past administrations. Dissident officials who stray from the president’s views have been inexorably excised from power.

That such total fealty is expected in Bush circles is unsurprising. Political decisions grounded in pragmatism, with the paramount goal of reaching a certain outcome (i.e., “maximize American security”), are always subject, by their nature, to rational debate and examination. The mission is to find the optimal method for reaching the desired destination.