A Stranger in the Kingdom (11 page)

Read A Stranger in the Kingdom Online

Authors: Howard Frank Mosher

“I be!” he said, and thrust his head forward to get a good look at my friend in the twilight. Resolvèd shook his head, as though he couldn't believe what he saw. “You say he's a-fishing?”

I nodded.

“Trout fishing?”

I nodded again.

“Well, Je-sus, that ain't no way to go about her. Tell him to hand that pole here to me.”

“Resolvèd says he wants your pole,” I told Nat, as though he and my cousin spoke two entirely different languages.

Nat handed him my fly rod. Resolvèd stuck the hammock contraption into the milkcan and stared at the size-twelve Royal Coachman wet fly on the end of Nat's leader. “What's this, a Christly bug?” he said, and ripped off the fly's wings with his three or four remaining side fangs.

From his hunting jacket pocket, Resolvèd removed a lead sinker hefty enough to take any freshwater bait imaginable to the bottom of Lake Memphremagog at its deepest point. He attached this anchor to Nat's leader about a foot above the denuded fly hook. He scowled at the ground for a moment. With the toe of his rubber barn boot, he overturned a dead limb that had dropped off the soft maple tree behind us. He stooped and came up with a nightcrawler as long as a small snake, which he threaded once through its middle onto the hook. He handed the rod back to Nat. From another pocket he produced a pint bottle of Old Duke with only a swallow or two left in the bottom, which he promptly drained off Closing one eye, he sighted along the neck of the empty bottle at a pinkish granite boulder in the river. “Does he see that rock out there?”

Nat nodded.

“Well, then, goddamn it, tell him to throw in beside it.”

For emphasis Resolvèd hurled the bottle end-over-end out into the river, where it smashed to smithereens on the boulder.

Nat threw in. Instantly his bait sank. A minute went by, during which all three of us watched the line intently. Another minute. Then the line began to move downstream.

“Tell him to wait.”

Nat lifted the rod tip slightly

“I said, tell him to wait!” Resolvèd shouted.

“Wait!” I shouted. “He says to wait.”

The line, just barely visible in the twilight, continued to cut down and across the current.

“Now!” Resolvèd roared. “Heave her!”

“Heave her!” I roared.

Nat reared back on my rod with both hands. A silvery, shimmering arc flew up out of the sawmill pool toward our heads.

“Good Christ!” Resolvèd shouted and ducked like a man who'd been shot at.

Dangling from a low branch of the soft maple tree eight or ten feet off the ground above us was a thrashing rainbow trout about a foot long.

“Treed!” Resolvèd said with some satisfaction, and picking up the milkcan with the hammock rolled up in it, he continued downstream and faded into the dusk.

Nat seemed amused by the whole episode. While I cleaned his trout, he asked me how Resolvèd and I were related. He didn't see, he said, how anyone as young as me could be cousin to a “bloody ancient codger” like Resolvèd.

“Well,” I said, as I slit open the trout's stomach sac to see what he'd been eating, “Resolvèd isn't really our cousin. We just call him that. What he is, is sort of an uncle to my father, I think.”

“Sort of an uncle?”

“Sort of a half-uncle, actually. Or a step-uncle. Let's see. If I've got this right, his father was my father's grandfather, old Mad Charlie. Mad Charlie had a second wife, a gypsy woman, and she was Resolvèd's mother. Dad could tell you all about it.”

“Mad Charlie!” Nat shook his head. “No wonder your cousin's an outlaw. Is he really an outlaw?”

“You bet he is. And a cockfighter and a moonshiner and the biggest poacher in Kingdom County. Last month he shot a moose through his kitchen window and got caught and fined fifty dollars, and I guess if my brother hadn't paid the fine for him he'd be in jail this minute.”

Nat laughed. “I'd never get used to this âKingdom' of yours, Kinneson, if I lived here a hundred years. What a place! Let's say we head home, eh? I'll never get to that chemistry at this rate.”

It was getting too late to fish, anyway. The spring peeper frogs along the edge of the river were singing like a thousand jingling sleigh bells, and it was almost pitch dark.

Just as we started up through the meadow, a blinding swatch of light illuminated a stretch of river several hundred yards downstream. In it I could see a dark figure bent over something in the water.

“Stop right there, Resolvèd Kinneson!” a high-pitched voice commanded. “You're underâ”

The figure in the river straightened up fast. A dark arm shot out toward the source of the beam. The light swept crazily across the night sky, looped over and over, and vanished. From downriver we heard loud splashings, grunts, curses.

Seconds later someone went crashing up through the bankside alders into the meadow.

Just downriver, Sheriff Whiteâfor that was undoubtedly who the high voice belonged toânow lightless, wallowed noisily back to the opposite shore.

“I saw you, poacher boy,” he shouted. “I saw you and I've got your net and your trout. You're under arrest for poaching and for assaulting an elected officer of the law.

“Go ahead and run,” the sheriff hollered. “Run to the woods, run to the hills, run to Charlie Kinneson. Run all the way to the Supreme Court, damn you. You're as good as behind bars already.”

But as Nat and I stole back up toward the farmhouse on the gool, trying to suppress our laughter, I was certain that I heard low chuckling near us in the puckerbrush.

Â

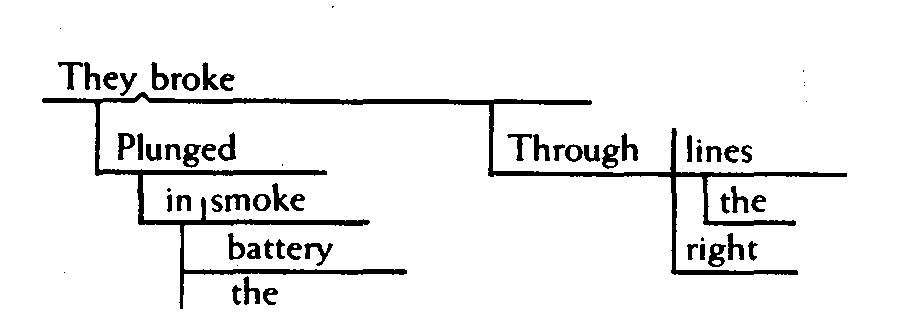

Plunged in the battery smoke

Right through the line they broke.

Â

I stared at the stern block letters on the blackboard. Unhelpfully, the letters stared back at me.

“We're waiting for you to diagram and parse that sentence, James Kinneson. We'll wait as long as we have to.”

Of that I had absolutely no doubt at all. Although school had officially ended for the day five minutes ago, not a student in Athena Allen's eighth-grade grammar class had budged one inch. Every set of eyes was on the poetic jewel on the blackboard, which I had been selected to diagram and parse. Parse! I had no earthly idea what the quotation even meant, much less how to break it down into its component parts of speech by means of arcane lines more suitable to a geometry exercise.

Ordinarily, I very much looked forward to Athena's end-of-the-day English class. She was a crackerjack teacher, every kid's favorite, full of fun and great stories: “Tell us the one about the Great White Whale, Miss Allen!” “Read us how old Huck meets up with the King and the Duke!” And because Athena had learned to fish and hunt with her father the judge long before she was our age, and still regularly fished and hunted with him and with Charlie, she was genuinely interested in our tiresomely predictable compositions about trout and grouse and deer and read them with genuine appreciation.

But as Charlie had often said, Athena Allen was a “high-toned woman,” and you definitely did not want to get on her wrong side. Not very oftenâjust frequently enough to keep us on our toesâshe would lose patience with the whole class and keep us after school for an hour or more, to “hammer the grammar” into our thick young heads (as Charlie said) and to show us that even though she was young and pretty and funny and sympathetic, she was still the boss.

I must say that those sessions were quite apt to follow close on the heels of Athena's fights with Charlie. And since I knew from my brother that they had just had a real donnybrook two days ago over Charlie standing her up the past Saturday night to go drinking in Canada with his basketball teammates, I was not surprised that lovely Athena was up on her high horse with us today.

I hated to be called on at those times, and I especially dreaded having to go to the front of the room. Even under ordinary circumstances this onerous pilgrimage was a real trial by fire in Athena's class, partly because Nathan Andrews and half a dozen other upperclassmen had a silent study period in the back of the room and so were on hand to witness my humiliation, and partly because when I returned to my seat I was invariably favored by a veritable barrage of kicks, jabs, punches, and missiles from Frenchy LaMott, who sat next to me, and who had the well-earned reputation of the worst boy in town.

The illegitimate son of Bumper Stevens, the commission sales auctioneer, Frenchy lived with his mother, Ida LaMott, and his two younger half-brothers at his uncle Hook LaMott's slaughterhouse out on the River Road. He was a good two years older than anyone else in our class and he hated Athena Allen with a passion because, although she was sympathetic to his circumstances and more than willing to give him extra help, she did not believe in social promotion and had flunked him twice already. Frenchy also resented Athena because two years ago her father, the judge, had sent him to the state reform school at Vergennes for several months. Suffice it to say that by the spring of 1952 Frenchy's single academic goal was to turn sixteen and “do for” Athena Allen once and for all, then quit school in a burst of glorious notoriety, an event to which he looked forward with more relish than any honor student ever anticipated delivering a valedictory.

But like it or not, I had been chosen to parse those idiotic lines on the board, and parse them I knew I must before any of us left that room. Worse yet, of all the days to be detained, today was one of the worst because this afternoon Resolvèd was slated to be arraigned at the courthouse for the trout-poaching episode Nat and I had witnessed. Of course Charlie would be representing him, and I desperately wanted to be on hand to see the fun.

Athena was looking out the window of her second-floor classroom, down onto the common. “What is so rare as a day in June?” she said. “I shall tell you, ladies and gentlemen: a day in May. A warm, pleasant day in May, like this day,” she continued. “A very pleasant day. A pleasant day to play baseball. Or go fishing. Or to parse sentences.”

Something hit the back of my head and bounced off onto the floor beside my desk. With a quick glance at Athena, who was still looking out the window and extolling spring, I bent over and picked up a tightly wadded piece of paper. At first I thought that this missive was a conventional spitball thrown at me by Frenchy. But at the back of the room Nat, who had stayed late to finish some homework, was signaling to me. “Read it,” his lips said silently.

I unfolded the paper, which just fit into the palm of my hand. On it I saw:

Â

Â

As quickly as possible, with several furtive glances at the crib sheet, I got up, transposed this marvel to the blackboard, and sat back down again.

Slowly, ever so slowly, Athena Allen turned away from the window and loomed down upon me. A yard away from my desk she stopped and turned to the blackboard. “Who wrote that, James Kinneson?”

“I wrote it, AthâMiss Allen.”

Ever so softly she said, “You wrote it.”

It was neither question nor statement. I cannot in fact say what it was. But its implications were dreadful.

“Yes, Miss Allen.”

“Then, James, let us parse. What, pray, is the subject?”

“The subject?”

“Yes. The subject.”

At that moment I could not have told the good woman what subject we were studying, much less the subject of that involuted sentence. She might as well have asked me to render the thing into Greek.

Dazed as I was, I vaguely recollected that the subject of a sentence was quite apt to come first. Looking hurriedly at the lines on the board, I said, “âPlunged.'”

From nearby came a nasty snicker.

“Who was that?” demanded Athena.

“Me,” said Frenchy LaMott. “What you going to do about it?”

Athena's eyes blazed angrily. I wouldn't have changed places with Frenchy at that moment for anything in the world. Then, to my amazement, Athena burst into laughter. “Frenchy,” she said, “you may not know much grammar, but you get an A-plus for honesty.

“Class,” she announced, “just this once, we will celebrate Mr. LaMott's honesty with an undeserved dismissal. Enjoy your afternoon in May.”

Â

“Working hard, James?”

I was on my way up the courthouse steps two at a time, hoping to catch at least the tail end of Resolvèd's poaching arraignment, when Plug Johnson, self-appointed president of the Folding Chair Club, hailed me from the top step.

Plug was standing near the main door of the courthouse with half a dozen other pensioners retired from the B and M Railroad and American Heritage Mill. There was no way for me to get by them without stopping.

Although none of these savants was noted for an altruistic concern for local youth, except to predict grimly that most of us would come to no good end because we did not know the meaning of the word “work” (all members of the Folding Chair Club having apparently gone to work full-time at the age of eight or nine), they indulged me in a patronizing and badgering sort of way because they liked and admired my brother. Also, as the local editor's son I was regarded as a potential pump for news and information, though I was under the strictest injunction from both my parents never to mention a word of anything I heard at the

Monitor

or at home to these nosy old gossips.