A Special Duty (17 page)

Authors: Jennifer Elkin

Partisans dispersed to recover the packages and to find Lieutenant Szylowski, who was injured in a bad landing and needed help. He was brought into the camp with his head bandaged up to a wholehearted welcome from the delighted Englishmen, who now felt sure their rescue was imminent. In the course of the next few days, delight turned to suspicion as Szylowski tried to get them drunk on vodka and spent most of the time interrogating them in the company of the political commissar, with whom he seemed particularly ‘pally’. He offered to send messages back to the airmen’s families, provided they used the normal RAF codes, and was keen to know the details of RAF briefings before an operation. During this questioning the crew realised that he was probably NKVD

9

and quietly tipped the vodka on the ground, or even up their sleeves; anything to remain sober. Szylowski on the other hand got very drunk and maudlin, saying to the crew: “When you come to bomb Moscow, don’t bomb, land and give them my name and tell them you once lived with Russian partisans – you will be alright”. The crew thought this a very odd thing for a supposed ally to say to them, but at this point Kunicki took Tom to one side and told him quietly of his own misgivings about sharing too much information with Szylowski. Kunicki and Tom had developed mutual respect during their daily treks in search of an airstrip and, although he commanded a Soviet unit, Kunicki was Polish. His loyalties must have been put to the test on many occasions.

xii

Szylowski checked out the chosen landing site and declared it unsuitable for a Dakota, but after a further search they found a cornfield near the village of Huta Krzeszowska that he was happy with. This posed an ethical dilemma for Kunicki, because the crop belonged to the entire village and they needed it to sustain them through the winter. It would have been a simple matter to compensate one farmer for the loss of his crop but a different prospect to pay off each individual household for their share. However this was the field selected by the expert, so Kunicki radioed the location to Kiev and decided that, if the village required compensation, he would settle the debt with cattle and grain obtained from raids. Kiev responded, and confirmed 5

th

June as the date for the extraction.

The proposed rescue mission gave Kunicki and his fellow Soviet commanders the opportunity to evacuate injured personnel and send important papers to Kiev and the couriers were kept busy liaising between the groups so that the best use was made of this opportunity. Meanwhile, Russian pilot Captain Vladimir Pavlov and his crew, all familiar with dangerous operations, were preparing for their most complicated assignment to date. Two Dakotas were to take part in the special operation behind enemy lines; the first to land and pick up personnel, including the British crew; the second to follow thirty minutes later and drop supplies. Pavlov, a modest and highly skilled pilot, was to carry the supplies. He carefully planned his route to take him over swampy and forested ground that he knew to be difficult for German anti-aircraft guns. In the event this proved unnecessary because they flew much of the way in thick cloud, and their main difficulty was navigating in the poor visibility. The skies cleared as they flew over the Styr River, but Navigator Dimitri Lisin could not be sure of the exact section of the river they were over to get a ‘fix’. However, the crew knew that once they were spotted they would get their ‘fix’, because anti-aircraft guns were positioned at bridges over the river and the highway; it was just a matter of waiting. And it wasn’t long before searchlights swept across the sky and tracer fire streaked past the window. Pavlov swung the plane away to the right to avoid the fire, and Lisin managed to establish his position – they were forty minutes flying time from their destination.

Preparations at the cornfield had to be left to the last minute so that the prepared ground would not be spotted by the enemy and so, on the evening of the 5

th

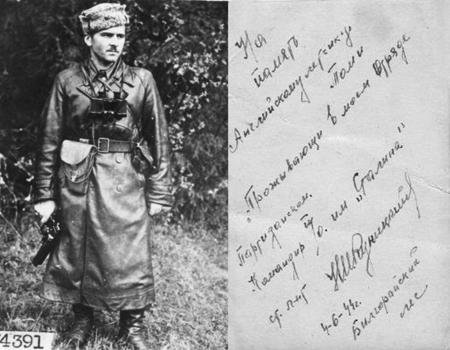

June, a partisan detachment from the area flattened and hardened the field with horse-drawn logs of wood, back and forth until the surface was solid enough to support the aircraft. Kunicki and Yakovlev’s men carried out diversionary attacks on the nearby German garrisons to keep attention away from the evacuation zone, and a one-thousand strong partisan contingent surrounded the field to defend it against attack, which was sure to come once the fires were lit. Then, in the distance, the unmistakable drone of a Dakota was heard, and the prepared flare path of three bonfires was set alight to guide the aircraft in. When Pavlov arrived over the field to drop his supplies he noticed that the first aircraft, which had taken off thirty minutes ahead of him, had not arrived, and this gave him a problem. If he dropped the packages they would leave indents in the field, making it impossible for the second aircraft to land. So in a courageous manoeuvre, knowing that the injured partisans and the British crew were waiting below, he brought his aircraft down on to the prepared strip. In the darkness he was unable to find the turning circle at the end of the cleared runway, and the swirling corn chaff blocked the engine air-intakes, which began to overheat. The crew climbed out and cleared the intakes by hand as partisans arrived to direct them to the turning circle. The airmen gave their weapons to Kunicki, who would have much greater need of them, and bade him farewell. A couple of days earlier they had posed for a photograph with Kunicki and Ducia, so that proof existed that they had been alive and well when handed over, and Kunicki gave Tom a photograph of himself as a souvenir. He wrote on the back, in Russian:

Mikolaj ‘Mucha’ Kunicki.

Photo given to Tom Storey as a souvenir June 1944

“In memory of the English aviator Tom, being in my partisan unit. Brigade Commander “Stalin” (Mikolaj Kunicki) 04.06.1944, Bilgoraj forest.”

Then the airmen, George, Szylowski, a group of badly-injured partisans, a pregnant woman, and important documents for Kiev were quickly loaded and Pavlov, though concerned about the excess weight of his aircraft, prepared to take off. The first two attempts failed, the Dakota stubbornly refused to move through the sandy trough into which it had settled. The engines shrieked and dust and corn chaff swirled around the plane and into the eyes of the partisans, who gathered behind the wings and tail and began to push. Heat radiated from the engines as the partisans heaved the plane until it began to move, and then Pavlov took over, slowly at first, gathering speed and, as the line of trees rushed towards them, lifting clear of the ground, almost brushing the tree tops, and disappearing into the night. The delay and the noise left the partisans on the ground exposed, and they were still trying to damp down the signal fires when two German bombers arrived over the stubble field firing heavily from machine guns and dropping bombs. Kunicki gave the order to shoot at the bombers, which eventually flew away without inflicting any casualties.

Pavlov flew close to the ground, carefully avoiding the area where they had been fired on during the outward journey, but then quite unexpectedly, a group of Germans on a riverbank below, startled by the sudden appearance of the aircraft, opened up with bursts of machine-gun fire, forcing Pavlov to throw the aircraft into a dive. The sudden manoeuvre caused injured passengers to fall from their benches and luggage to tumble around them. Bullets whistled past, clunking into the metal frame, and a piece of metal flew past Tom’s head and punched a hole in the cabin roof, through which a stream of air came rushing. Pavlov had his eyes glued to the ground trying to avoid the fire, while inside the blacked-out plane, one of the airmen was trying to find water for the pregnant woman, who was crying in pain. Pavlov’s crew exchanged silent glances of relief when the danger had passed and Tom expressed his admiration for the skill and daring of the crew: “It was a good job”, he said.

Soviet Dakota crew: Left to Right: Vasili Kostin (2

nd

pilot), Dimitri Lisin (navigator), Vladimir Pavlov (captain), Ivan Shevtsov (wireless operator). Engineer Alexander Kniazkowa not shown.

Some years later, Kunicki wrote the following words to Patrick Stradling regarding this rescue:

“We regarded you as the luckiest people in the world that I succeeded to get you out, because I do not know what would happen to you, whether your families and England would ever see you, because the bullets do not choose. It is a matter of fact I often said in those hard times, when we were encircled, that it was a good thing that I sent you away, but it would be better for me to have Paddy at my side because he was a very good shooter of all kinds of firearms. In those battles not only were four additional partisans of great help, but also even one man was of great significance.”

xiii

Eddie and Hap had been transported by cattle truck to Stalag Luft 6, in East Prussia (now Lithuania), where they received their POW numbers – 3694 for Eddie, and 3607 for Hap. Not a comfortable journey on a passenger train this time, but a cramped and uncomfortable four-day trip in a cattle truck. In fact they were treated like cattle, even down to the straw on the floor of the truck. The camp held a few thousand British, American, Canadian, and Polish Air Force prisoners-of-war, and the senior British NCO running things was Warrant Officer James ‘Dixie’ Deans, a bomber pilot who spoke fluent German and commanded the respect of both the prisoners and their guards at the Heyderkrug camp. Red Cross parcels were received regularly, with a proportion of the contents going to the cookhouse to ensure that everyone had at least one meal a day, and other items kept back for bartering with some of the guards. They were interrogated by special investigators on the 17

th

May, along with another RAF crew, who they then didn’t see again. Thinking they may have been moved on for more intensive questioning, Eddie and Hap were concerned for their welfare and raised the matter with Deans, who reassured them: “Don’t worry, Red Cross keep a special eye on you chaps”.

xiv

There was no Red Cross to keep an eye on Walter, who was living a precarious existence, constantly in fear of being discovered by German patrols that would suddenly arrive at the house, or swoop on the village and take young people for slave labour. Daily life at the cottage was hard, but despite the Germans having taken most of their cows, they had two left and Mrs Dec made butter from the milk and they had eggs from the hens. Walter learned to forage for mushrooms, some of which could provide an entire meal for the family. Even poisonous fungi were gathered to use as a fly-killer on the windowsill. Forest fruits and leaves were collected for making tea, and Mr Dec grew tobacco plants, drying the leaves on top of the bread oven. Walter found it hard to watch his ‘

matka

’ struggle through her daily chores, and on one occasion tried to help as she walked barefoot to the fields carrying a load on her back and pushing a sack truck with her feet. Mr Dec immediately intervened and gave the load back to his wife, and Walter had to learn not to interfere in a way of life which had rules beyond his comprehension. In June he was visited by a Home Army officer from Warsaw, who gave him 5,000 zloty, and told him to ‘lie low’ and to expect an aircraft. His hopes of rescue were raised, but no aircraft arrived. His days in the Dec family home were drawing to a close, and it was with a sense of apprehension that he listened to the sound of the approaching Russian army. He still naively believed that, being Allies, everything would be alright once they arrived, but the next phase of his ordeal was just beginning.

xv

Back home in England, his parents and fiancée Winnie received clandestine information that Walter was safe and living on a farm in Poland, though this information was to be kept secret for fear of comprising his safety and that of his protectors. There would be a long wait for his homecoming.

xvi

1

Storey debrief to Brigadier Hill (ANNEX II) 15

th

June 1944 (CAB 66/53/47) TNA

2

Translation of a document found in Russian Archives (courtesy of Paul Lashmar)

3

B. G. Shangin, commander of a Ukrainian partisan unit.