A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (39 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

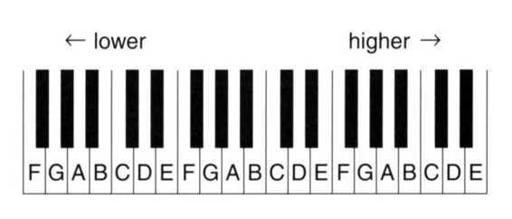

The Staff. Most music is written on a five-line horizontal template called a staff (plural staves). Each line and each space on the staff corresponds to one of the white keys on the keyboard. Each of the keys sounds a specific musical pitch, and each of the pitches has a letter-name. The white keys on the keyboard have the letter-names A through G; these letters are repeated up and down the keyboard, as shown in Figure A-1.

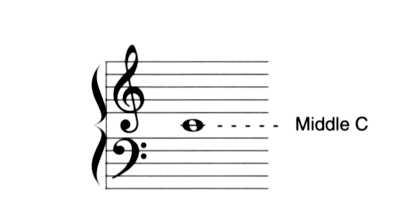

Since there are 52 white keys on an 88-note piano keyboard, and only five lines on the staff (plus the four spaces between the lines), at any given point in the music only a small number of musical pitches can be indicated on any given staff. The symbol that tells us which set of pitches the staff is assigned to is called a clef The clef appears at the left end of each staff. Several clefs are in common use, but the main ones you need to know about - the only ones used in this book - are the treble clef and the bass clef. These clefs are shown in Figure A-2.

Figure A-1. The white keys on the keyboard have letter-names. Seven letters are used, so the letter-names repeat. Pay close attention to the positions of the black keys in relation to the letter-names. Lower pitches are to the left, higher pitches to the right.

Figure A-2. The treble clef (top) and bass clef (bottom) indicate specific ranges on the keyboard. To find Middle C, locate the lowest C on the keyboard and count upward. If you're using a five-octave electronic keyboard, Middle C is the third C counting up from the bottom. If you're using a piano or equivalent 88-note keyboard, Middle C is the fourth C.

Mnemonics are often used to remember the letter-names on the staves. In the treble clef, the five lines (from bottom to top) are E, G, B, D, and F, which could stand for "every good boy does fine:' The spaces in the treble clef (again, from bottom to top) are F, A, C, and E, which spells "face" In the bass clef, the lines are G, B, D, F, A ("good boys do fine always"), and the spaces are A, C, E, G ("all cows eat grass").

In music written for the piano, two staves are normally employed, as shown in Figure A-3. Together they're known as the Grand Staff.

Figure A-3. Piano music is written on the Grand Staff, which combines two staves, one with treble clef and the other with bass clef. Middle C is written with one ledger line either above the bass clef or below the treble clef. In actual sheet music, the treble and bass staves will be further apart; they're placed close together in this figure to make it clear that the ledger line containing Middle C is the only line that would fall between them.

When notes are too high or too low to be placed on a staff, given the clef currently assigned to that staff, short lines are placed above or below the staff so that more lines and spaces are available. These short lines are called ledger lines.

Notes. To indicate which notes are to be played, dots are placed on the staff. The dots can be either hollow or filled in, and can have stems attached to them or, in some cases, no stem. Actually, noteheads are bigger than dots; dots are also used in notation, and have a different meaning. The vertical position of the notehead on the staff - the line or space where it's placed - indicates which pitch is to be played. The noteheads and the stems attached to them are of various types. Each type indicates a rhythmic duration. The duration of a note is the length of time it sustains, from start to finish.

Musicians measure time in beats. The beat is a steady pulse, which could come from a metronome or drum machine, from tapping your foot, or from a conductor waving a stick. The pulse may be very slow, or it may be very fast. While the speed of the beats may make a big difference for both the audience and the musicians themselves, it doesn't affect the way the music is notated. A beat will look just the same on paper, whether the speed of the beat (which musicians refer to as the tempo) is slow or fast.

A long note may last for a number of beats, while a short note may last for only a fraction of a beat. If 16 notes are crowded into one beat, the music may sound fast to the listeners, even though the beat is slow.

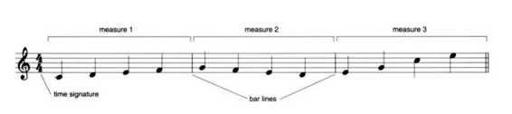

Beats are grouped into measures. The most common type of grouping puts four beats into each measure. Other groupings with two, three, five, six, or more beats per measure are also found, but the nomenclature (the naming system) most often used for describing note durations is based on the idea that there are four beats per measure. Measures are separated from one another using vertical lines called bar lines.

The type of note that lasts for one beat is called a quarter-note. (There are some exceptions to this rule, but we're not going to worry about them in this extremely basic overview.) Quarter-notes and bar lines are shown in Figure A-4. The quarter-note gets its name from the fact that there is room for four of them in a single four-beat measure. A quarter-note has a solid notehead and a vertical stem. The stem can point either up or down. Music engravers have some rules about whether the stem on a particular note should point up or down, but those rules aren't too important when you're first learning to read music.

Figure A-4. As explained in Chapter Four, the time signature shows how many beats are included in each measure (the top number) and the type of note that counts for one beat (the bottom number). A time signature appears near the left end of the first staff. In 4/4 time, as shown here, there are four quarter-notes (solid noteheads with stems) in each measure. Measures are separated by bar lines.

Notes that are shorter than quarter-notes have flags or beams attached to their stems. Notes that are longer than quarter-notes have hollow note-heads. Figure A-5 shows some of the note values that are used most often. When a shorter note appears by itself, it has a flag. When several shorter notes appear together in one beat, the flags are extended horizontally to form one or more beams, which connect all of the notes. The beam shows how the beats are grouped. (Beams are not used for this purpose in vocal music.)

Figure A-5. Each of the types of notes shown has a different length. A quarter-note lasts for one beat; all of the other notes are longer or shorter. There are two quarter-notes in a half-note, two eighth-notes in a quarter-note, four sixteenth-notes in a quarter-note (or two sixteenth-notes in an eighth-note), and so on.

Figure A-6. A dot after a notehead increases its duration by 50%. Since a half-note has the same length as two quarter-notes, a dotted half-note lasts for three quarter-notes, and so on.

Figure A-7. The three half-notes in measure I are played together as a chord. Then the two quarter-notes in this measure are played separately, first the E and then the C. In measure 2, the two eighth-notes are played separately, then the three quarter-notes together as a chord, and finally the half-note by itself. While doing this, keep a steady count, as indicated beneath the staff.

The duration of any note can be extended by 50% by placing a dot after the note head, as shown in Figure A-6. For instance, a quarter-note normally has the same length as two eighth-notes, but a dotted quarter-note has the same length as three eighth-notes.

All of the notes that are to be played on the same beat are aligned vertically on the staff. Often, they'll be connected by a single stem. Music is read from left to right, so notes that are positioned horizontally are to be played one after another. While reading the music, it's important to keep a steady beat, so that the lengths of the notes are clear (see Figure A-7).