A Perfect Madness (47 page)

Authors: Frank H. Marsh

Tags: #romance, #world war ii, #love story, #nazi, #prague, #holocaust, #hitler, #jewish, #eugenics

Erich thought a minute before

answering Julia’s question, then responded slowly as if he had

rehearsed his words. “I sort of holed up in Triberg to get away

from everything and everybody. The war left too many scars,

especially in my family. A lot of veterans would come there to soak

their crippled bodies in the springs. I figured it was a good place

to set up my psychiatry practice. It never did get big,

though.”

“

Did you try and find

me?”

“

Yes, many times, but I

got nowhere. I went back to Prague several times looking for you,

but thought—”

“

That I had died with the

rest of the Jews? That’s what you were going to say, wasn’t it?”

Julia said curtly, interrupting Erich.

“

No, but what you say will

do.”

“

You have a beautiful

daughter, you know, with your ocean blue eyes and sharp nose.”

Julia blurted out, frustrated at Erich’s guarded manner.

Then Julia told him of Anna and

Scotland and Hiram’s death over Dresden and all she had done during

the war, including the killing of Martin Drossen. But when she

mentioned the photograph and Maria’s name, Erich became restless,

clenching his hands tightly, as if the first of many stories

carefully wrapped and long hidden in the past was about to be

opened. Julia could not help but see the sudden agitation in

him.

“

Did you know a Maria

Drossen? She was from Mainz.”

Erich paused for a second before

answering her question, carefully selecting his words.

“

Perhaps. There was a

Maria Drossen with me at Görden Hospital.” Erich hesitated, then

stopped talking, realizing what he might have revealed.

Julia knew of Görden and the

euthanizing of handicapped children and mental patients there, and

the black horror of Erich’s sudden confession quickly cleared her

mind of any compassion she still felt for his pitiful humanity. The

love for the Erich she once knew was still there, but she hated the

man standing before her.

“

You killed babies at

Görden, and people who were mentally ill. How could you, Erich?”

Julia demanded.

“

Things just changed, got

all mixed up. I was a good doctor who began treating people by

putting them out of their miserable existence. Isn’t that what you

and I were trained to do as doctors, to ease suffering?”

Julia remained utterly stupefied and

silent, looking at Erich, a man she no longer knew. What he had

done so long ago was lost somewhere deep down inside of him,

playing games with his mind, keeping him believing that what had

happened never did. To him, what he and others had done was so

totally unbelievable that he was incapable of believing it ever

took place.

“

I know you were at

Auschwitz, Erich. And I know you murdered my mother and father.

That is why I hoped you would come, so that you could hear these

words.”

At first, Erich looked puzzled by

Julia’s strong words and accusations for several seconds, but then

began to cry. He had come looking for his soul in the only place it

might be found, with Julia. And she had shut the door, leaving only

God to open it.

“

I was only a doctor,

Julia, nothing more. My hands killed no one there.”

“

They loved you and took

you into their home and broke bread with you, Erich, and yet you

denied them their last shred of humanity by refusing to speak to

them, to even say their names before they died. How could you be so

cruel?”

“

I had no choice, Julia,

with the children at Görden, or with your mother and father. They

would have died anyway,” Erich said, sobbing loudly.

“

No, I won’t accept that.

There were many choices for you.”

“

Not when one is afraid of

dying, as I was. It’s a terrible thing to live with fear, and

surviving was all that mattered to me then, to live and see you

again.”

“

An either/or always

exists. God has seen to that. You should know that as a good

Lutheran. You could have at least fought as a soldier for your

country. I could have accepted that.”

“

You don’t understand. All

I want is forgiveness from you,” Erich cried, sinking to his

knees.

“

I understand very well,”

Julia said, her voice trembling. “I can forgive you for what you

are and have become, but only those that are dead can forgive you

for what you have done. And that is between you and God to work

out.”

With Julia denying him forgiveness,

Erich struggled to his feet, leaning on Rabbi Loew’s gravestone,

and shouted out in anger, “What about Dresden? Shouldn’t you and

the world and even Hiram ask forgiveness for that terrible night of

hell? My mother and father were burned alive, too, with thousands

of others, all for nothing.”

Erich’s words hit Julia hard. He had

become the accuser, and she had no ready reply. Whether or not the

bombing of Dresden, as it was done, was wrong, she didn’t know. She

had killed Germans, too, but they were soldiers, and in war that

should lift the mantle of guilt a little, even though it never does

for some. All that she did know now in listening to Erich was that

there was nothing left of who he once was as a man.

“

I am sorry about your

parents. Perhaps their deaths were wrong, I don’t know, but a

thousand Dresdens would never excuse what you and all the other

doctors did, hiding behind the mask of Hippocrates. They were only

Jews, Erich, nothing more, trying to live their lives out as God

intended for them,” Julia said, almost in a whisper, as if trying

to calm the soul of Rabbi Loew, whose grave they were standing

on.

His anger stilled, Erich looked around

at the shadows bouncing off the gravestones by passing lights, as

if those buried had suddenly come alive to play for a while. He had

watched them many times before when he and Julia would secretly

huddle here, unafraid of what any tomorrow might bring. But for

fifty years he had been afraid, and that was his life. Looking back

at Julia as the shadows crossed her face, too, for one brief moment

he remembered how innocently beautiful she was when he looked at

her the very first time. And it was still there, unmarred by her

aging wrinkles. Speaking now in a soft voice, tinged with a strange

finality, he said, “Those moments of forever that we shared so long

ago really did exist, didn’t they?”

“

Perhaps, I don’t know.

Memory can make a thing seem more than it was or ever could be. I

must go now, Erich,” Julia responded coldly, turning to leave the

cemetery. Pausing at the small gate, she looked back one last time

at the man she still loved.

“

To me they did exist,”

she said, then left.

When Julia finished with the story,

the last she would ever tell Anna, or anyone else, she took Anna’s

hands and placed them over her dying heart. Fighting for each

breath, her voice barely audible to Anna, she whispered, “Erich was

your father, Anna. I loved him more than life itself, but he

betrayed me. And, like Papa, I will never know why. We were only

Jews.”

It was the only time Julia ever

acknowledged that Erich was Anna’s father, though Anna had always

believed it to be true. But the words from Julia made her love her

mother that much more. Taking Julia in her arms, Anna held her

close, just as her mother had done with Eva, until she passed from

this world, speaking Erich’s name with her last breath. Perhaps,

Anna thought, looking at the gentle, still face of her mother, one

can love completely without a complete understanding. And Julia

knew enough to know that for her it was enough to have loved

him.

It was night now, and the throngs of

visitors to the Holocaust Memorial at the Pinkas Synagogue and

cemetery would be gone, leaving those buried there once more alone.

Anna left the hotel with the box holding Julia’s ashes and walked

the six blocks to the cemetery. Her long journey home was nearing

an end. Unlatching the small gate, she stepped gingerly into the

graveyard, immediately feeling the soft and lumpy sod beneath her

feet. With each step she stood on a grave, quickly becoming lost

among the thousands of stones rising before her like ghosts from

the darkness. Standing still, Anna tried to recall where Rabbi

Loew’s grave was located and began making her way slowly through

the maze of graves surrounding her until she finally came upon the

sacred plot.

Kneeling down, she took a silver

tablespoon from her purse and lifted a small square of the soft sod

next to Rabbi Loew’s grave and cleared away several inches of the

rich, black soil beneath it. For a few seconds she held the box of

ashes close to her breast, caressing it softly before sprinkling

the contents into the shallow grave. After covering the ashes with

the plug of sod, Anna leaned forward and kissed the tiny grave and

whispered, “There really was a golem when you were young, I

know.”

She left, feeling good about all that

had happened today in satisfying the promise to her mother. The

heavy spring rains would come soon to Prague, and Julia’s ashes

would sink deeper, nourishing and bringing new life to the soil

around her, as she had done so often to all who knew

her.

As her final story, Julia had come to

rest at last among a hundred thousand Jews who knew her not and her

dear childhood friends, the golem and Rabbi Loew. She would remain

here for eternity, Anna believed, in her most sacred

place.

###

About the Author

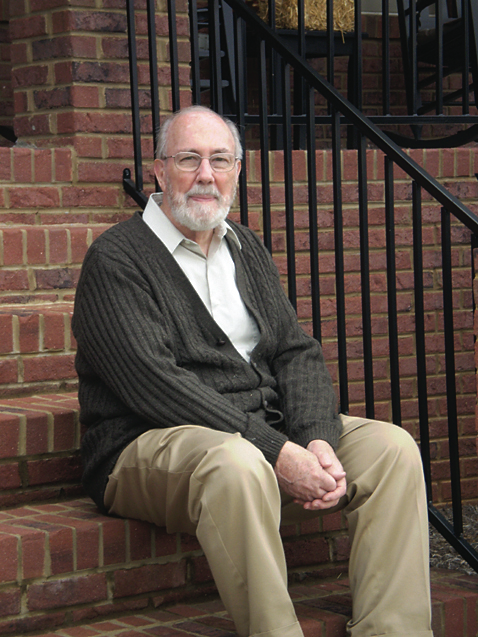

F

rank Marsh was a

trial attorney for twenty-five years and then a university

professor of philosophy, law, and bioethics. He has published six

books in bioethics, numerous articles, and scripted documentaries

dealing with medicine, genetics, and law. He is also the author of

the novel

Rebekka’s Children.

Other Books by Frank

Marsh

Fiction

Rebekka’s Children

Nonfiction

Biology, Crime and Ethics

Medicine and Money

In Defense of Political

Trials

Punishment and

Restitution

Children in Treatment for Mental and

Physical Catastrophic Diseases