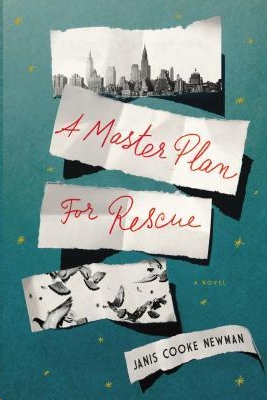

A Master Plan for Rescue

Read A Master Plan for Rescue Online

Authors: Janis Cooke Newman

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #Literary, #Coming of Age

ALSO BY JANIS COOKE NEWMAN

Mary: Mrs. A. Lincoln

The Russian Word for Snow

R

IVERHEAD

B

OOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright © 2015 by Janis Cooke Newman

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Newman, Janis Cooke.

A master plan for rescue : a novel / Janis Cooke Newman.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-698-18401-5

I. Title.

PS3614.E626M38 2015 2015004284

813'.6—dc23

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

To my father,

who told me his stories

T

his is the moment I spend the rest of my life trying to return to:

The three of us sitting around the table my father and I have painted red to match The Flash’s cape. A shade, I now know, that doesn’t belong in a kitchen, but it was my father who suggested bringing the comic book to the paint store on Dyckman Street.

It’s early December, and the clanging of the radiator mixes with the violins that spill from the speakers of the Silvertone radio. I know the Silvertone is on, because it is always on. My grandfather, a man once known as the Gentleman Bootlegger, a man who is dead by this time, claimed that music during meals is what separates man from beast, and so my mother—his daughter—puts on music. But we never listen to it. Instead, we sit above bowls that smell of gravy and spices and talk over each other, sometimes banging our silverware on the red table for attention. The three of us—my father, mother, and me—in our small apartment at the northern tip of Manhattan.

In this moment, though, there is only the clanging of the radiator and the violins. We have stopped talking so my father and I can watch my mother add up numbers inside her head.

Because that is what she can do. Her ability.

Though to be more accurate, it’s my father who is watching her. I am watching him. And I’m realizing, for the first time—and probably because I am so close to turning twelve—that it isn’t the feat of her adding up those numbers he enjoys so much. It’s the way she’s sliding the tip of a No. 2 pencil into and out of the gap between her front teeth.

And now that I’ve noticed this, I cannot remember a single time my father has taken that pencil back and checked her answer. I can only remember him doing exactly what he’s doing now. Gazing at her mouth, her eyes—the exact shade of green the Hudson River gets on a clear day—her long swoops of black hair.

In the pocket of the black Mass pants I have not yet had time to change out of is something rare I am waiting to show my father. This morning, during Father Barry’s sermon, I found the stub of a Mass candle caught under my kneeler, and I’ve spent the past hour melting its wax into the hollow of a perfectly round beer bottle cap, creating an object I believe will make me unbeatable at the game of skully.

I’m, at best, a mediocre skully player. However, with this new skully cap—this Holy Skully Cap—it will be as if God Himself is directing my thumb every time I flick my cap across the chalked squares of the board. As if His Mighty Force is propelling my cap into that of another player, one filled merely with the wax of a melted crayon.

As I wait, I imagine myself dropping the Holy Skully Cap into my father’s hand, telling him the story of finding the candle, melting the wax. I know that when I’ve finished this story, my father will lift his eyes—brown like mine—and run them over me, reading me. I know, too, that he will understand all the powers I believe the Holy Skully Cap to possess without me having to say them aloud.

Because that is what he can do. His ability.

I do not yet have an ability. I am only an almost-twelve-year-old boy, small for my age, black-haired like my mother, wanting no more than for the life I have to keep going as it is.

All these things are held in that moment. Everything I am about to lose. My mother adding up numbers inside her head. My father watching as she slides the tip of a No. 2 pencil into and out of the gap between her teeth. Me with something rare I am waiting to show my father.

It has been a cold day, the temperature barely making it into the twenties. But the chill has thinned the air and the sky is clear. The last rays of sunlight slant through the front windows of our apartment, and though it is only mid-afternoon, there is a sense of the day ending. That nostalgic Sunday afternoon feeling of wishing to remain exactly where you are.

Those things, too, are held in that moment, the moment before the violins turn into words. Turn into

Surprise attack

and

Japanese bombs

and

Pearl Harbor.

It is my father’s hand I’m looking at when my eyes go bad.

My father’s hands are not like anyone else’s. The skin in the creases has been bleached white by the chemicals he uses to develop his photographs. My father shoots portraits, and I think of these white marks as the ghosts of every picture he has ever taken.

It’s these white marks that disappear first, blurring into nothingness, like ghosts vanishing. Then the hand itself. The edges melting away, dissolving into a table painted a red that doesn’t belong in a kitchen.

My eyes dart around the room, but everything has turned into a mass of color, as if the outline of each object—the icebox, the stove, the window over the sink—has been erased, as if the boundaries that keep the color of one thing from invading another no longer exist. And what I think—what I can only think—is that it is the Japanese. That they, with their bombs, have knocked the entire world out of focus.

I search for my father, stare into the space where a second ago, he was sitting. But there’s nothing there except the brownish-red smudge of the wallpaper, and it feels like those bombs have sucked all the air out of the room along with the outlines of things, because I cannot breathe, can only gasp.

I hurl my arm into the place where my father had been, stunned that the Japanese could have taken him from me, amazed at their evil magic. My hand collides with something, the bones of his chest, the worn fabric of his shirt. My father shifts in his chair, drops his hand over mine, and I realize that his reddish hair, the Sunday stubble on his face, his brown shirt have all merged with the wallpaper behind him, turning him invisible. I press the flat of my hand against his chest until I can feel his heart beating.

And that’s better, but only a little. Because now Aunt May—my mother’s sister—and Uncle Glenn are in our kitchen, which I know only by the sound of their voices. The two of them, up from their apartment one floor below. And I have the sense from the confident movement of their blurs—Uncle Glenn’s pudgy and beer-colored, Aunt May’s still in the navy blue suit she wore to Mass—that they do not see our kitchen as an unnavigable smudge of color. And I’m figuring out, by the way Aunt May is clattering what sounds like rosary beads on the table, and saying we should all go straight back to Good Shepherd and repeat a thousand Hail Marys for peace, saying to my father, “Yes, even you, Denis,” my father having long declared that Ireland more than cured him of Catholicism; and by the way Uncle Glenn keeps repeating that first thing tomorrow morning he’s going to Whitehall Street and joining up; and by how the black-haired blur of my mother is heading for the living room, shouting back that everybody needs to pipe down, because she can’t hear the radio, that it is only me who is seeing the world this way.

And that is worse. Much worse.

I take my hand off my father’s chest and press both palms into my eyes until I see sparks of light, and then I press harder, as if that light is a mechanism for fixing what has gone wrong. But when I open my eyes, nothing has changed. Or, I suppose, everything has.

I have to say something

, I’m thinking.

Tell somebody

. But I can’t pull enough air into my lungs for speech. And even if I could, everybody is talking. About the Japanese. And their bombs.

Except my father, who hasn’t moved, hasn’t spoken. Who, I believe, has been running his eyes over me, reading me.

“Jack,” he says. “How many fingers?”

But I cannot tell he has raised his hand.