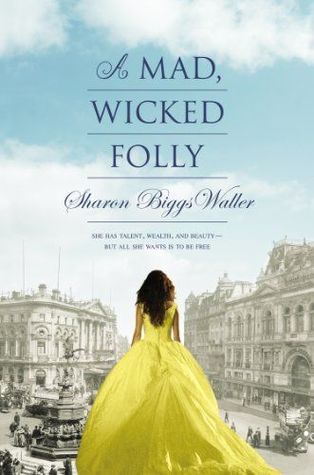

A Mad, Wicked Folly

Read A Mad, Wicked Folly Online

Authors: Sharon Biggs Waller

MAD,

WICKED

FOLLY

A

Sharon BiggsWaller

iking

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

New Zealand ◆ India ◆ South Africa ◆ China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published in the United States of America by Viking,

an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Sharon Biggs Waller

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes

free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition

of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or

distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting

writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Printed in U.S.A.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Designed by Kate Renner

or my aunt,

Shirley Atchison Steinert.

Thank you for believing in me

and for being my very first editor,

all those years ago.

A M AD, WICK ED, FOLLY

MAP TK

I

am most anxious to enlist everyone who

can speak or write to join in checking this mad,

wicked folly of “Women’s Rights” with all its

attendant horrors, on which her poor feeble sex

is bent, forgetting every sense of womanly

feelings and propriety.

Trouville, France, Monsieur Marcel Tondreau’s atelier,

Monday, first of March, 1909

NEVER SET OUT

to pose nude. I didn’t, honestly. But

when the opportunity arose, I took it. I sat with the

other artists that morning in Monsieur Tondreau’s tiny

atelier in the French village of Trouville waiting for

Bernadette, our usual model, to arrive. Some tinkered with

their charcoals and pencils; others adjusted their easels. A

few of the artists stared at the stage as if the model would

magically appear if they looked hard enough. Monsieur

bustled around in his canvas smock, moving the model’s chair into the light, plumping the bolsters. The studio

smelled of turpentine, linseed oil, and charcoal, and there

was no sweeter perfume in the world to me than that.

Étienne, one of the other artists, yawned, leaned back

in his chair, and closed his eyes.

“Hungover, old fellow?” his friend Bertram whispered.

“Is fair Bernadette in the same state?”

Étienne grunted a warning but did not open his eyes.

“Poor Étienne,” I whispered. “He looks unwell, Bertram.

Let him be.”

Bertram reached for his pencil, sharpened it with his

knife, and began to sketch a cartoon of Étienne. “It’s hard

to feel sorry for a chap who has inflicted illness upon himself and caused the malaise of our model, once again.” He

added devil’s horns to the line drawing and then nudged

Étienne’s boot with his own. Étienne cracked open one

bloodshot eye and then closed it. “He lacks the artist’s discipline but possesses all of his foibles.”

“We all have our faults, Bertie.” I knew I shouldn’t side

with Étienne; he was a rapscallion. But I also knew him

to be a talented artist, and this, in my eyes, meant he’d

earned the right to roguish behavior every now and then.

“If he had half your discipline, my dear Vicky, he would

be lucky,” Bertram said.

I smiled and began my own sketch of Étienne, this one

with angel’s wings. Bertram saw what I was doing, grinned,

and shook his head.

I had made Bertram’s and Étienne’s acquaintance last

autumn when I was drawing my best friend, Lily, in the

village square. They plonked themselves down at our table

as though we knew them and watched me as I worked.

I was about to tell them to keep to themselves, when

Bertram blurted out, “You’re very good.” But then he spoilt

it by adding, “For a girl.”

After I found out they were students of a local artist, Marcel Tondreau, and studied with him at his atelier,

I wouldn’t let them leave until they told me about him. I

was self-taught, apart from a few watercolor classes at finishing school, and I had always longed to attend an atelier

like that, but my parents did not approve of such a thing. I

begged Bertram and Étienne to introduce me to the artist.

To my delight, I found that Monsieur was a rare person in

the world of art. He didn’t care if the artist was male or

female; he let the work speak.

All of the other artists at the atelier were male, and

none of them gave me a thought apart from the occasional

curious glance. I did not blame them. Most females drew

things that did not matter.

But the other artists were wrong about me. I didn’t fill

my head with airy nothings or paint watercolors of kittens

and flowers meant only for decoration; I wanted so much

more.

When I was ten years old, I laid eyes for the first time

on a painting called

A Mermaid

, which hung in the Royal

Academy in London. The mermaid’s eyes seemed to call to

me, telling me that creating someone like her was within

my grasp. And like her maker, J. W. Waterhouse, I wanted

to be considered among the best artists in the world. I

wanted critics to laud my work. But most of all, I wanted

to express myself through my art as I fancied, and not be

told what or whom I could draw or paint. For all of these

dreams I needed knowledge and the connection with other

artists who could introduce me to the mysterious society

that made up the art world.

No one at my boarding school, Madame Édith’s

Finishing School for Girls, knew I attended the atelier—

not the headmistress nor any of my fellow students, apart

from Lily, who helped me sneak away. If they knew, it

would be hell’s delight, because Monsieur Tondreau’s atelier was not the kind females should frequent. At Monsieur

Tondreau’s we drew from the undraped figure—the nude.

No woman of good breeding would ever do such a thing,

which was another reason why female artists were not

taken seriously. Sometimes women could draw from nude

statues without fear of scandal. The South Kensington

Museum in London held drawing classes for women, but

the instructors covered the male statues’ bits with tin fig

leaves. Apparently, gazing at a statue’s male anatomy was

equivalent to staring into the sun.

Monsieur Tondreau glanced at his pocket watch and

sighed. “

Alors

. I think that Mademoiselle Bernadette will

not be with us today.” He leveled a look at Étienne, who

was cradling his head in his hands. “So. We say good-bye

for the day, or we have a student pose.” Monsieur’s gaze

flitted over the artists briefly and then lit on Bertram.

“I’m not doing it again.” Bertram raised his voice over

the artists’ calls of encouragement. “Once was enough.”

“Who wants to draw your scrawny carcass again anyway,” came a voice from the back of the room.

“I nominate Étienne,” Bertram went on. “He’s the

cause of all this grief.” He stood up, grinning, and dragged

Étienne to his feet by the shoulder of his jacket. Several

students shouted out in agreement. Étienne took this all in

humor for about ten seconds before slapping his hand over

his mouth, turning a very sickly shade of yellow, and running for the back door that led to the outdoor privy. Sounds

of retching echoed through the room.

“Can you not find a model who resists Étienne’s charms,

Monsieur?” one of the artists asked. “This is the second

time Bernadette has failed to show after a night out with

him.”

“I’m sick to the back teeth of drawing the blokes,”

Bertram added. “Hell’s bells, I can draw my own phallus at

home. We need to draw women, Monsieur.”

“I will try, but it is difficult to find women who are willing. Or one whose father will let her.” He looked over the

group again, but his eyes did not fall on me. “If no one will

volunteer, then I shall bid you all farewell.

À demain

.”

“Why does she not pose?” demanded Pierre, a burly

artist from Paris, who had pointedly ignored me from the

day I walked into the studio. “Everyone here has had a

turn. Why not her?”

I twisted in my seat and scowled at him. “My name is

Vicky!”

Pierre shrugged. “I only learn names of people who

matter,

Vicky

.”

“Don’t be an ass, Pierre,” Bertram said. “She’s just a girl.”

There it was again: I was just a girl.

“

Pardonnez-moi!

” Pierre replied. “I thought she was an

artist. She pretends to be.”

I turned back in my seat and stared at my easel. I felt

the gaze of several of the artists fall upon me. Everyone

in the room

had

posed before. Everyone but me. And that

awful voice inside me started up. That little voice that

always reared its head when I didn’t feel confident about

my work:

No wonder none of the artists give you a thought.

Why should they? You aren’t really one of them.

It was true, wasn’t it? I wasn’t willing to do what the

other students did for art. Who was I to call myself an artist? If I didn’t take my turn then I would always be

just a

girl.

Certainly never an artist in the other students’ eyes.

And then the words burbled out: “I’ll do it! I’ll pose.”

Monsieur Tondreau’s whiskered face registered surprise.

Pierre looked taken aback for a moment, but then I

thought I saw a little flicker of respect in his eyes. “Well,

then, mademoiselle. I was wrong. Maybe you aren’t pretending, after all.” He bowed slightly, sat back down in his

chair, and began to set up his easel.

“I didn’t mean

you

, Vicky,” Bertram said.

I stood. “The other artists here have taken their turn.

Pierre is quite right. I should do my bit.”

“A moment, gents.” Bertram took me by the elbow and

led me off to the corner. He leaned in close. “Vicky, you

know female models have more to lose than male ones. No

one cares if a bloke gets his kit off.”

“If I’m going to be a student here, treated on equal terms,

then I have to be willing to do everything that they do,” I

said. “There can’t be two sets of expectations, one for them

and one for me, the only girl in the class. How will I earn

their esteem if I don’t pose?” I threw a glance over my shoulder at the students watching us. Pierre sat with his arms

folded; the look of respect was now replaced with a sneer.

“Are you going to try to tell me that you care what

Pierre thinks? That great buffoon? The only one who you

should care about is Monsieur Tondreau, and he thinks the

sun shines out your arse. Take my advice: let your fabulous

work speak for you, and forget about what everyone else

says or thinks. Pose if you want to, by all means, but don’t

do it because you feel you have to. A model should never

be forced; you know that, Vicky.”

“I’m not forced.” I jerked my arm out of Bertram’s grasp

and marched to the front of the room. I wouldn’t say that I

wasn’t afraid, because I would be lying. My legs were trembling so much I was surprised my knees didn’t clack together.

Mercifully, Monsieur came forward and helped me up

onto the dais. He threw open the creaky blue shutters to let

in as much light as the gloomy day would allow.

I was going to do this. I was really going to do this!

I

turned my back and let my breath out. I had no idea how to

begin. When Bertram disrobed to model, he made it funny,

pretending to be a fan dancer at the Folies Bergère, taking

each item of clothing off and throwing it to us, eyes rolling

comically while we whooped and shouted.

I decided to do the opposite, to act as if disrobing in

front of a group of men was no great thing. I started to undo

my blouse, but my hands shook and my fingers slipped off

the buttons. I squeezed my hands into fists and tried again.

No one spoke a word as I undressed, but I could hear

the usual bustle of artists readying their easels and drawing boards—the rustling of paper and the scrape of pencils

against knives. I slid my skirt and petticoats off, put them

neatly to one side, turned around and sat down on the

chair. I stared at my bare toes for the longest time, unable

to find the nerve to look up. It was the first occasion in my

life that male eyes had seen my unclothed body. I’d never

cared what men thought of me before, but now, sitting in

front of their steady gaze, I wondered how they regarded

my breasts, my hips, my legs. I found I wanted them to see

me as beautiful. In my own experience I’d looked at the

men’s bodies in that way when they posed. I was human

after all, and the model wasn’t a

thing

, a bowl of apples to

be drawn.

Finally, I forced myself to lift my head. And I saw ten

pairs of eyes looking back at me. I had no idea what they

were thinking, because Monsieur’s students were professional and had learned to focus their minds on their work.

They knew if they gave in to any urges—leering or making bawdy comments—Monsieur would dismiss them and

they’d never be allowed back.

And so the artists regarded me frankly and then bent to

their work. Only one of the newer artists, a boy about my

age, gaped, his eyes out on stalks, jaw dangling. I could see

his throat tighten when he swallowed. I met his gaze and

raised my eyebrows. Startled, he knocked over his easel,

his pencils and papers scattering over the floor, earning

disgusted looks from the more experienced artists. He

fumbled to gather up his things, his ears red.

Bertram remained in the corner with his hands in his

pockets. I tilted my head toward his easel. He hesitated for

a moment, opened his mouth to say something. But then he

shrugged, went back to his workplace, and began to draw.

I felt my shoulders relaxing, my nerves disappearing.

I felt like Queen Boadicea taking on the Romans. I leaned

forward, propped my chin in my hand, and stared out at

the boys.

Now I’m one of you.