A Little History of the World (41 page)

Read A Little History of the World Online

Authors: E. H. Gombrich,Clifford Harper

All this was happening at about the time when European envoys first returned to Japan, a land forbidden to foreigners for more than two hundred years. To these white-skinned ambassadors, life in Japanese cities – with their millions of inhabitants, the houses made of paper and bamboo, the ornamental gardens and pretty ladies with their hair piled high upon their heads, the bright temple-banners, the rigid formality, and the solemn and lordly manner of the sword-bearing knights – was all delightfully comical. In their filthy outdoor boots they trampled over the priceless mats of the palace floor where the Japanese only trod barefoot. They saw no reason to respect any of the ancient customs of a people they thought of as savages, when exchanging greetings with them or drinking tea. So they were soon detested. When a party of American travellers failed to stand aside politely, as was the custom, when an important prince happened to pass by in his sedan chair, together with his entourage, the enraged attendants fell on the Americans and a woman was killed. Of course, straight away British gunships bombarded the town, and the Japanese feared they were about to suffer the same fate as the Chinese. Fortunately, the rebellion had meanwhile been successful. The emperor – known in Europe as the Mikado – now really did have unlimited power. Backed by clever advisers who were never seen in public, he decided to use it to protect the country against arrogant foreigners for all time. The ancient culture must be preserved. All they needed was to learn Europe’s latest inventions. And so, all at once, the doors were thrown open to foreigners.

The emperor commissioned German officers to create a modern army, and Englishmen to build a modern fleet. He sent Japanese to Europe to study Western medicine and to find out about all the other branches of Western knowledge which had made Europe so powerful. Following the example of the Germans he established compulsory education, so that his people would be trained to fight. The Europeans were delighted. What sensible little people the Japanese had turned out to be, opening up their country in this way. They made haste to sell them everything they wanted and showed them everything they asked to see. Within a few decades the Japanese had learnt all that Europe could teach them about machines for war and for peace. And once they had done so, they complimented the Europeans politely, as they once more stood at their gates: ‘Now we know what you know. Now

our

steamships will go out in search of trade and conquest, and

our

cannons will fire on peaceful cities if anyone in them dares harm a Japanese citizen.’ The Europeans couldn’t get over it, nor have they, even today. For the Japanese turned out to be the best students in all the history of the world.

While Japan was beginning to liberate itself, very important things were also happening across the seas in America. As you remember, the English trading posts which had grown into coastal cities on America’s eastern seaboard had declared their independence from England in 1776 in order to found a confederation of free states. British and Spanish settlers had meanwhile pressed on towards the west, fighting Indian tribes as they went. You must have read books about cowboys and Indians, so you’ll know what it was like. How farmers built log cabins and cleared the dense forest and how they fought. How cowboys looked after enormous herds of cattle and how the Wild West was settled by adventurers and gold diggers. New states sprang up everywhere on land taken from the tribes, although, as you can imagine, not much of that land had been cultivated. But the states were all very different from each other. Those in southern, tropical regions lived off great plantations where cotton or sugar cane was cultivated on a gigantic scale. The settlers owned vast tracts of land and the work was done by negro slaves bought in Africa. They were very badly treated.

Further north it was different. It is less hot and the climate is more like our own. So there you found farms and towns, not unlike those the British emigrants had left behind them, only on a much larger scale. They didn’t need slaves because it was easier and cheaper to do the work themselves. And so the townsfolk of the northern states, who were mostly pious Christians, thought it shameful that the Confederation, founded in accordance with the principles of human rights, should keep slaves as people had in pagan antiquity. The southern states explained that they needed negro slaves because without them they would be ruined. No white man, they said, could endure working in such heat and, in any case, negroes weren’t born to be free … and so on and so forth. In 1820 a compromise was reached. The states which lay to the south of an agreed line would keep slaves, those to the north would not.

In the long run, however, the shame of an economy based on slave labour was intolerable. And yet it seemed that little could be done. The southern states, with their huge plantations, were far stronger and richer than the northern farm lands and were determined not to give in at any cost. But they met their match in President Abraham Lincoln. He was a man with no ordinary destiny. He grew up as a simple farm boy in the backwoods, fought in 1832 in a war against an Indian chief called Black Hawk, and became the postmaster of a small town. There in his spare time he studied law, before becoming a lawyer and a member of parliament. As such he fought against slavery and made himself thoroughly hated by the plantation owners of the southern states. Despite this, he was elected president in 1861. The southern states immediately declared themselves independent of the United States, and founded their own Confederation of slave states.

Seventy-five thousand volunteers made themselves available to Lincoln straight away. Despite this, the outlook was very bad for the northerners. Britain, which had abolished and condemned slave labour in its own colonies for several decades, was nevertheless supporting the slave states. There was a frightful and bloody civil war. Yet, in the end, the northerners’ bravery and tenacity prevailed, and in 1865 Lincoln was able to enter the capital of the southern states to the cheers of liberated slaves. Eleven days later, while at the theatre, he was murdered by a southerner. But his work was done. The reunited, free, United States of America soon became the richest and most powerful country in the world. And it even seems to manage without slaves.

WO

N

EW

S

TATES IN

E

UROPE

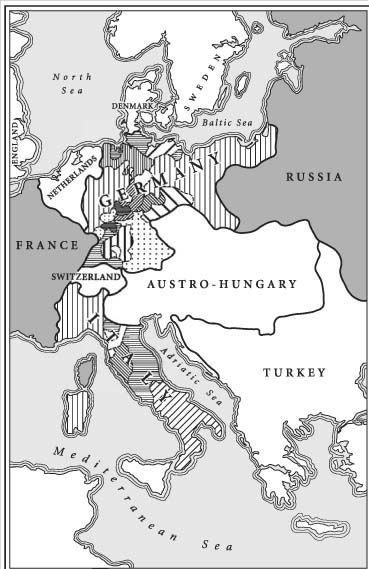

In this Europe (if we ignore Britain, which was at this time more concerned with its colonies in America, India and Australia than with the neighbouring continent), there were three important powers. In the centre of Europe stood the empire of Austria. There the emperor Franz Josef had been ruling from the Imperial Palace in Vienna since 1848. I saw him once myself, when I was a little boy. He was by then an old man, and was crossing the park at the Palace of Schönbrunn. I also have a very clear memory of his state funeral. He really was what an emperor was meant to be. He ruled over all sorts of different peoples and countries. He was emperor of Austria, but he was also king of Hungary and count-elevated-to-the-rank-of-prince of the Tirol and had lots of other ancient titles, such as king of Jerusalem and protector of the Sacred Tomb – a title that went back to the Crusades. Many provinces of Italy came under his authority, while others were ruled by members of his family. Then there were the Croats, the Serbs, the Czechs, the Slovenes, the Slovaks, the Poles and innumerable other peoples. For this reason, the words on old Austrian banknotes (for example, ‘ten crowns’) also appeared in all these other languages. The emperor of Austria even had some power, at least in name, in the German principalities. But the situation there was rather complicated. When Napoleon shattered the last remnants of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in 1806, the German empire had ceased to exist. The many German-speaking lands – which included Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover, Frankfurt, Brunswick and so on and so forth – then formed an association, known as the German Confederation, to which Austria also belonged. All in all it was a remarkably confusing picture, this German Confederation. Each speck of land had its own prince, its own money, its own stamps and its own official uniform. It was bad enough when it took several days to get from Berlin to Munich by mail-coach. But now that the same journey took less than a day by train, it had become almost unendurable.

This is what the map of central Europe looked like before Italy and Germany had become states. At the same time as all these little pieces of land were uniting to create those two powerful states, the Turkish empire was breaking up into an ever-increasing number of independent countries.

The patchwork presented by the lands of Germany, Austria and Italy was quite unlike anything around them on the map.

To the west was France. Shortly after the revolution of 1848, it had once again become an empire. One of Napoleon’s descendants had been able to reawaken memories of the glory of the past and although far from great himself, he was first elected president of the republic and soon afterwards, emperor of France under the name of Napoleon III. Despite all its wars and revolutions, France was now an exceptionally rich and powerful country, with great industrial cities.