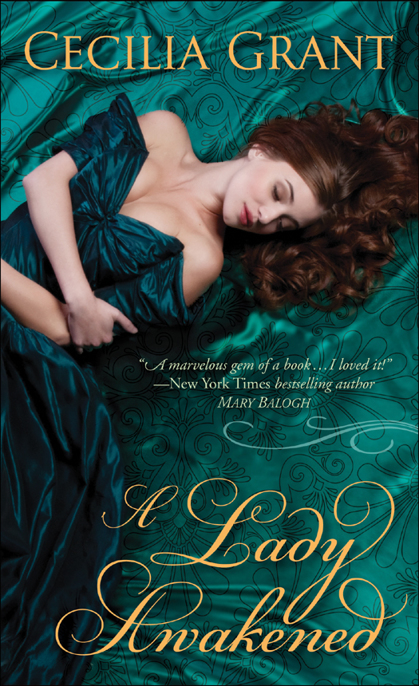

A Lady Awakened (45 page)

Authors: Cecilia Grant

Neither did Fortune find him worthy of notice, this time. He enriched Mr. Roanoke by twenty pounds in one hand and thirty in the next, erasing over a third of the evening’s gain. Let that teach him to get caught up in petty intrigues. He pushed away from the table in disgust.

* * *

T

HIS HAD

been someone’s house, before it became a club of most lax membership. Walls had been knocked out here and there to create the necessary large salons and supper room, but some traces of the residential scale remained. A drawing room at the back of the second story, for example, currently occupied by ladies who did not care for cards. Will turned away from the brightness and chatter and, on the street side of the same floor, found a modest library, intact even to books. No candles lit, or fire in the grate, but that only increased the likelihood he’d have the room to himself.

A bookshelf jutted out at right angles to the single bay window, and on the shadow side loomed a shape that proved, on approach, to be an armchair. Perfect. He sank into it and closed his eyes. Through the open door he could hear the house’s sounds, all remote and indistinct. Conversation. Laughter. A faint strain of music—violin?—from the ballroom one story below. No doubt there would be dancing later. Just one of those artful amenities that proclaimed this house to be no seedy Smith and Pope’s, but a place of gentlemanly sport. Where a gentleman could waltz with courtesans, and drink himself into a stupor, and ruin himself to the benefit of his fellows instead of some impersonal proprietor.

And who are you to condemn them for it

? He slouched deeper into the chair, folding his arms. It seemed sometimes he’d lost all ability to … enjoy himself, carelessly. As a man ought to do, indeed as he had used to do. Nearly eight months he’d been back in England, turning aside invitations and ducking from acquaintances, schoolfellows, with whom he couldn’t seem to remember how to converse. Only thick-skinned, cheerful Cathcart had persisted, and the viscount had finally prevailed not through the power of friendship but because he’d dangled the lure of a gaming club just when Will discovered a need for several thousand pounds.

Some hard edge was imposing itself against his forearm. Some square shape in his breast pocket that he hadn’t any recollection of—

Oh, Christ. The snuffbox. This was the coat he’d worn when he’d first called on Mrs. Talbot.

He felt inside his pocket and drew out the box, then stood and reached round the bookshelf until moonlight through the window bathed his open palm.

Such a pretty thing for a man of modest means to have owned. Gold clasp, gold hinges, the lid all enameled with a scene of horse and hounds. Probably it was worth a bit of money. That was why it had stayed in his pocket, once he’d seen the Talbot relations pawing over the other small items he’d returned. When Mrs. Talbot was able to be independent of those people he would put it into her hands that she might keep it for the child. She wouldn’t want for money, so there’d be no temptation to sell it.

His fist closed over the box, and opened again. He tilted his hand and the enamel gleamed as the moonlight caught it just so.

Altogether too much thinking he’d done tonight. He’d be useless at cards if he couldn’t quiet the rest of his brain. He closed his hand on the box again, and brought it back.

He was just stowing it in a pocket when footsteps sounded in the corridor. For no good reason he withdrew to the armchair with its shadows, whisking his legs back to keep his Hessians away from the spill of moonlight. Unaccountable reflexes a man brought back from war. It wasn’t as though the French had made a practice of sneaking up on one soldier at a time. Nor, of course, was it likely that the footsteps, if indeed they were bound for this room, could represent any threat.

Two sets of footsteps there were, one lighter than the other, and unmistakably bound his way. A man and woman. Yes, he ought to have anticipated this. Often enough he’d made like use of a darkened room at some gathering in his carefree days.

Something stopped him immediately rising. The awkwardness, perhaps, of having to explain just why he’d been in here, alone, in the dark. The stubborn assertion that he’d been here first, and why should he have to give way to their sordid purpose? At all events he was still seated, all the way in shadow, when two shapes filled the doorway and came in. The taller shape swung the door gently to behind them, and as the swath of illumination from the hall grew narrower, a green-jeweled cuff link glinted faintly.

Roanoke and his mistress. Or perhaps Roanoke and some other woman—indeed that was the likelier case, given Prince Square-jaw could entertain his mistress at home, at his leisure, without need for skulking about. The door clicked shut and Will abandoned the idea of a prompt exit. They could get on with their business and he’d slip out while their attention was engaged. Perhaps he’d make some attempt to ascertain the lady’s identity—for what purpose, though? If the man betrayed Miss Slaughter, that was nothing to do with him. Did he propose to finagle a seat next to her at supper, and drop vague dire hints of what he’d seen?

The question was moot. The pair made straight for the bay window and he knew her by her posture alone. Erect and somehow remote, as though holding herself apart from the very air through which she moved. They passed into the bay—he could almost have put out a hand and touched her skirts as she went by; thank goodness their eyes were not so well adjusted to the dark as his—and the draperies creaked along their rod; the thin gruel of moonlight grew thinner. Then, silence, save for a few vague rustles. Whatever their next order of business, it apparently required no preamble of conversation.

Doubtless there were men who would enjoy sitting here, clandestine witness to such goings-on. A pity one of them couldn’t take his place. All he’d wanted was a quarter-hour of darkness and silence; now he must tax his weary brain by calculating how best to retreat undetected from this room which he, by any measure, had the better right to occupy.

He’d make his try in thirty seconds. Any sooner, and they might not be sufficiently oblivious. Much later, and he’d be more visible to their dark-acclimated eyes.

An indistinct utterance added itself to the rustles. His hands settled carefully on the chair’s arms and gripped there. Twenty seconds. No more.

Confound these rutting fools, both of them. Confound her especially, for letting Prince Square-jaw make this use of her not forty minutes after he’d bandied her name about so despicably. Did she have no care at all for her dignity? Then henceforth neither would he. No more misguided gallantry for Cathcart to twit him with.

Nineteen, twenty. They sounded absorbed enough. Slowly he eased up from the chair, angling round the bookshelf for a furtive glance to assure himself they wouldn’t notice him.

He stopped, half-risen.

He’d been prepared for something sordid, a brute coupling between an importunate boor and a harlot who’d learned her trade at Mrs. Parrish’s. And of course it

was

sordid by its very nature, this retreat to the library, and Square-jaw himself was everything sordid, with his mouth at the juncture of her neck and shoulder and his hands groping here and there.

She

, though. She was … Confound him if he could even begin to find the right word. He only knew

sordid

wasn’t anywhere close.

She stood with her back to the drapery, eyes closed, chin lifted, whole person swaying with pleasure. While he watched she sent her arms—ungloved, he could now see—up the wall behind her where they twisted overhead, wrists crossing with serpentine grace. Like one of those dancers in a story who bewitched men into cutting off other men’s heads. Her naked fingers closed over a fold of the velvet drapery and he knew how that velvet would feel to her, thick and lush-grained, a cat’s purr made tactile. Knew, too, how it would feel to be the velvet, trapped unprotesting in her hand. He found a grip on the bookshelf and held on tight.

Down her arm he dragged his attention, down the sinuous curve until his eyes rested again on her uptilted face. Had he thought her less than beautiful? In moonlight, even in such scant moonlight, he could see the truth. Her bold features carved up the shadows and threw them helter-skelter, light and darkness dancing giddily over her nose and cheeks and chin. Her skin was pale as the moon itself, pale and tantalizing as an opal at the bottom of a clear still lake. Pale throat. Pale shoulder. Pale bosom, magnificently formed and half spilling out from the disarranged bodice. But he would not let his gaze linger there. Indeed he ought to be removing himself altogether, as he’d meant to do.

One last look at her face. Her head tipped a few degrees left and then a few degrees right as though to stretch the muscles of her neck. Her chin came down, rearranging the composition of shadows and light. And her eyes opened and looked directly into his.

She said nothing. She didn’t jump away from her lover, or yank up the bodice he’d tugged down, or cross her arms modestly before her. Only her eyes, widened and showing an excess of white, betrayed her consciousness of exposure. And that, for only a second or two, though the interval was sufficient to make him feel like a thoroughgoing cad.

The bookshelf’s edge bit hard into his hand. He couldn’t seem to look away, let alone make an apologetic bow and hasten from the room. He stood, frozen, as she regained her composure and her face hardened into the unmistakable lines of defiance:

Judge me if you dare

. Then that expression too subsided and only her falcon-like blankness remained. She looked through him, and past him, and altogether away.

He’d ceased to merit her notice. Whether he watched, or not, was a matter of supremest indifference to her. Her hands came down from their place on the curtain—even now, with a dancer’s lissome grace—and settled on the oblivious biceps of Mr. Roanoke, who had continued at her shoulder and neck through the brief drama but was now commencing to haul up her skirts.

And finally Will let go his grip on the bookshelf. He didn’t want to see what followed. He’d probably see it in his dreams, and that would be torment enough.

Some impulse of obstinacy made him bow. She didn’t look his way, and neither did she or Prince Square-jaw glance up as he stole light-footed to the door, opened it just enough to accommodate his long-overdue exit, and soundlessly closed it behind him.