A History of the Crusades-Vol 3 (31 page)

1245: A Uniate Patriarchate at Antioch

Bohemond had little control over the

Military Orders settled in his dominions; but they had grown more cautious. In

an attempt to reconcile the Commune of Antioch, with its strong Greek element,

the Papacy, it seems with Bohemond’s approval, changed its policy towards the

Orthodox Church there. It was clearly impossible now to integrate the Greeks

and Latins into one Church. So Honorius III offered the Greeks an autonomous

Church with its own hierarchy and ritual, so long as the Greek Patriarch would

recognize the supreme authority of Rome. The Greek clergy refused the offer,

possibly with the secret encouragement of Bohemond, who considered that an

independent Greek hierarchy would be more tractable; and the Patriarch Symeon

bustled off to the anti-Latin Council summoned by the Nicaean Emperor at

Nymphaeum, where the Pope was solemnly excommunicated. But when Symeon died,

about the year 1240, his successor David, in whose appointment it may be that

the Princess Lucienne had some part, was willing to enter into negotiations. In

1245 Pope Innocent IV sent the Franciscan, Lorenzo of Orta, to the East with

instructions that the Greeks who acknowledged Papal ecclesiastical suzerainty

were to be put everywhere on the same footing as the Latins. They need only

obey Latin superiors where there was a good historical precedent for it. The

Patriarch was invited to dispatch a mission to Rome, at the Pope’s expense, to

discuss disputed points. David accepted these terms. About the same time the

Latin Patriarch, Albert, who was not entirely pleased with the arrangements,

went off to France to attend a Council at Lyons, where he died. The next Latin

Patriarch, Opizon Fieschi, the Pope’s nephew, was not appointed till 1247 and

came to Antioch the following year. In the meantime David was the only

Patriarch resident at Antioch. But on David’s death, the date of which is

unknown, his successor Euthymius rejected Papal authority, for which he was

excommunicated by Opizon and banished from the city.

A large party in the Jacobite Church had

already made its submission to Rome. In 1237 the Jacobite Patriarch, Ignatius

of Antioch, while visiting Jerusalem, took part in a Latin procession and was

given a Dominican habit, after making an Orthodox declaration of faith. On his

return to Antioch he carried many of his clergy with him, and Latins were

officially told that they might confess to Jacobite priests, when Latin

confessors were not available. In 1245 a Papal emissary, Andrew of Longjumeau,

visited Ignatius at Mardin, where he had his main residence; and the terms for

union were negotiated. Ignatius was prepared to accept a verbal formula about

doctrine and administrative autonomy under the direct suzerainty of Rome. But

unfortunately Ignatius spoke only for one party of the Jacobite Church. There

was already a feud between the Jacobites of northern Syria and those of the

eastern and southern provinces; and the latter disregarded the union. So long

as Ignatius lived, his followers remained loyal to the Latins. But after his

death in 1252 there was a dispute over the succession. The pro-Latin candidate,

John of Aleppo, triumphed for a time, but considered that his Lath friends had

given him insufficient support, while his rival, Denys, who eventually

displaced him, was consistently opposed to them. Only a small portion of the

Church, based on Tripoli, maintained the union.

1252: Scandals in the Church of Antioch

The work to achieve union had been carried

out mainly by the preaching friars, Dominicans and Franciscans, who had begun

operations in the East soon after the foundation of their Orders. In the

restricted kingdom of Jerusalem they did not find much scope; but they were

particularly active in the Patriarchate of Antioch, the Patriarch Albert being

their devoted patron. They tended more and more to replace the secular clergy

in the scattered dioceses of the Patriarchate. The relations of the Patriarchs

with the new monastic order of the Cistercians were less happy. Peter II,

himself a former Cistercian abbot, had installed them in two monasteries, Saint

George of Jubin, near Antioch, and Belmont near Tripoli. But various scandals

arose during the Patriarchate of Albert; and a series of appeals to Rome had to

be made before order was reintroduced into the monasteries and the Patriarch’s

authority made good.

Bohemond V himself took little interest in

these proceedings. He seldom visited Antioch, but held his Court at Tripoli. As

in the kingdom, the various elements in his dominions drifted apart, saved from

extinction by the quarrels of the Ayubites and by a newer and tremendous force

that was beginning to agitate the Moslem world, the Empire of the Mongols.

BOOK III

THE MONGOLS AND THE MAMELUKS

CHAPTER

I

THE

COMING OF THE MONGOLS

‘

His

chariots shall be as a whirlwind! his horses are swifter than eagles. Woe unto

us; for we are spoiled.

’ JEREMIAH IV, 13

In the year 1167, twenty years before

Saladin reconquered Jerusalem for Islam, a boy was born far away on the banks

of the river Onon in north-

eastern

Asia to a Mongol chieftain named Yesugai and his wife Hoelun. The child was

called Temujin, but he is better known in history by his later name of Jenghiz-Khan.

The Mongols were a group of tribes living on the upper Amur river, and

perpetually at war with their eastern neighbours, the Tartars. Yesugai's

grandfather Qabul-Khan had welded them together into a loose confederacy; but

after his death his kingdom had disintegrated, and the Chin Emperor of Northern

China had established his suzerainty over the whole district. Yesugai inherited

only a small portion of the old confederacy, but he increased his power and his

reputation by defeating and conquering some of the

Tartar tribes and by interfering in the

affairs of the most civilized of his immediate neighbours, the Khan of the

Keraits.

The Keraits, who were a semi-nomadic

people of Turkish origin, inhabited the country round the Orkhon river in

modern Outer Mongolia. Early in the eleventh century their ruler had been

converted to Nestorian Christianity, together with most of his subjects; and

the conversion brought the Keraits into touch with the Uighur Turks, amongst

whom were many Nestorians. The Uighurs had developed a settled culture in their

home in the Tarim valley and the Turfan depression and had evolved an alphabet

for the Turkish language, based on Syriac letters. In earlier times Manichaeism

had been their dominant religion. Now the Manichaeans tended under Chinese

influence to become Buddhist. The power of the Uighur was waning, but their

civilization had spread over the Keraits and over the Naiman Turks whose

country lay between.

About the year 1170 the Kerait Khan Qurjakuz,

son of Merghus-Khan, died, and his son Toghrul had some difficulty in securing

the inheritance against the opposition of his brothers and uncles. In the

course of his fratricidal wars he secured the help of Yesugai, who became his

sworn brother. This friendship gave Yesugai a superior position amongst the

Mongol chieftains; but before he could establish himself as the chief Mongol

Khan he died, poisoned by some Tartar nomads, whose evening meal he was

sharing. His eldest son, Temujin, was then nine years old.

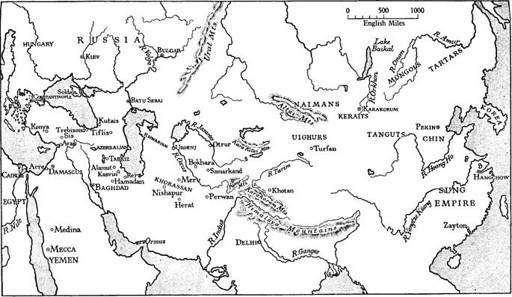

Map

3. The Mongol Empire.

The energy of Yesugai’s widow, Hoelun,

preserved for the young chieftain some authority over his father’s tribes. But

Temujin’s childhood was stormy. He showed himself to be a leader while still a

boy, and he was ruthless towards his rivals, even amongst his own family. In

the course of the wars by which he won a hegemony over the Mongols, he was for

a while a captive in the hands of the Tayichiut tribe, and his wife Borke, whom

he married when he was seventeen, was held prisoner for some months by the

Merkit Turks of Lake Baikal; the legitimacy of her eldest son, Juji, who was

born during this captivity, was always therefore suspect. Temujin’s growing

successes were largely due to his alliance with the Kerait Khan, Toghrul, whom

he affected to regard as a father and who helped him in his wars against the

Merkits. About the year 1194 Temujin was elected king or khan of all the

Mongols, and took the name of Jenghiz, the Strong. Soon afterwards, the Chin

Emperor recognized Jenghiz as chief prince of the Mongols and secured his

alliance against the Tartars, who had been threatening China. A swift war

resulted in the subjection of the Tartars to Jenghiz’s rule. When Toghrul-Khan

was driven from the Kerait throne in 1197, it was Jenghiz who restored him. In

1199 Jenghiz combined forces with Toghrul-Khan to defeat the Naiman Turks; but

it was not long before he grew jealous of the power of the Keraits. Toghrul was

now the chief potentate in the Eastern Steppes. He had the title of Wang-Khan,

or Ong-Khan, which filtered through to western Asia in the more familiar and

euphonious form of Johannes, thus making him a candidate for the role of

Prester John. But he was a bloodthirsty and treacherous man, singularly lacking

in Christian virtues; nor was he ever able to bring help to his

fellow-Christians. In 1203 he quarrelled with Jenghiz. Their first battle, at

Khalakhaljit Elet, was indecisive; but a few weeks later the Kerait army was

exterminated at Jejer Undur, in the heart of the Kerait land. Toghrul was

killed as he fled for refuge. The members of his family that survived submitted

to Jenghiz, who annexed the whole country.

1206: Organization of Jenghiz-Khan’s Empire

The Naiman were the next nation to be

subdued, in 1204, at a great battle at Chakirmaut where the whole fate of

Jenghiz’s power was at stake. Wars during the next two years established Jenghiz

as supreme over all the tribes between the Tarim basin, the river Amur and the

Great Wall of China. In 1206 a Kuriltay, or assembly, of all his subject-tribes

held on the banks of the river Onon confirmed his kingly title; and he

proclaimed that his people should be known collectively as the Mongols.

Jenghiz-Khan’s Empire was basically a

conglomeration of clans. He made no attempt to interfere with the old

organization of the tribes as clans under hereditary chieftains. He merely

superimposed his own family, the Altin Uruk or Golden Clan, and set up a

central government controlled by his own household and familiars, and he placed

under the free clans large numbers of slaves taken from the tribes that had

resisted him and been conquered. Serfs in thousands were given to his relations

and friends. At the Kuriltay of 1206 his mother Hoelun and his brother Temughe Otichin

were each given ten thousand families as chattels and his young sons five or

six thousand each. Tribes and even cities that submitted to him peaceably were

left without interference, so long as they respected his overriding laws and

paid to his tax-collectors the heavy tribute that he demanded. To bind his

countries together he promulgated a code of laws, the Yasa, which was to

supersede the customary laws of the Steppes. The Yasa, which was issued in

instalments throughout his reign, laid down specifically the rights and

privileges of the clan-chieftains, the conditions of military and other

services due to the Khan, the principles of taxation, as well as of criminal,

civil and commercial law. Supreme autocrat though he was, Jenghiz intended that

he and his successors should be bound by the law.

As soon as the administration of his

empire was arranged, Jenghiz set about its expansion. He had now a large army,

to whose organization he had also given careful attention. Every tribesman

between the ages of fourteen and sixty was by Mongol and Turkish tradition

liable to military service; and the great annual winter hunting expeditions,

necessary for providing meat for the army and the Court, served as manoeuvres

to keep the soldiers in training. By temperament the tribesmen were used to

give to their leaders an unquestioning obedience; and the leaders, from bitter

experience, knew that they must now obey the Khan. His subjects had also, like

all nomadic tribes, a yearning to move beyond the horizon, and a fear lest their

pasture-lands and forests should be exhausted. The Khan offered them new

countries and great booty and hordes of slaves. It was an army of cavalry,

archers and lancers mounted on swift ponies, men and beasts accustomed from

birth to hard living and to making long journeys across deserts with very

little food and drink. Such a combination of speed of movement, discipline and

vast numbers had never before been known.