A History of Britain, Volume 3 (12 page)

Read A History of Britain, Volume 3 Online

Authors: Simon Schama

She was 38. Godwin, the supreme rationalist, was distraught. He wrote to a friend, ‘My wife is now dead … I firmly believe that there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy. I have not the least expectation that I can now ever know happiness again.’ It was the best and most unlikely epitaph: that she had been the bearer of happiness to the man who had declared war on marriage. Through Mary, the thinker had learned to feel. Through Godwin, the creature of feeling had recovered her power of thought. Wollstonecraft is properly remembered as the founder of modern feminism; for making a statement, still powerful in its clarity, that the whole nature of women was not to be confused with their biology. But nature, biology, had killed her.

On 17 October 1797, the Austrian Empire gritted its teeth and made its peace at the Italian town of Campo Formio with a 28-year-old Corsican called Bonaparte, whom no one (in Vienna at any rate) had heard of a few years before. Napoleon did so without waiting for permission from his civilian masters in the Directory. But since much of Italy, including some of the greatest cities and richest territories, now passed either into French control or under its influence, the Directors were hardly likely to repudiate their military prodigy. The ending of the war with Austria now allowed France to redeploy a large number of troops to a different theatre and its one remaining enemy. Within a month more than 100,000 of them were camped between Rouen – William the Conqueror’s old capital – and the Channel coast. The point of the massive troop concentration was not lost on Pitt’s government. Suddenly the world seemed a more dangerous place.

Since the war with the French Republic had begun in 1793 it had been an axiom in Westminster that, sooner or later, the revolutionary origins of that state would prove its military ruin; that an army built from rabble would, after an initial burst of self-deluded energy, collapse in on itself. The Terror’s habit of guillotining its own generals, should they be careless enough to lose the odd battle, only confirmed this diagnois. But with Bonaparte’s Italian campaign, so shocking in its speed and completeness, and with the French tightening their grip on a whole swathe of continental territory from the Netherlands down through the Rhineland, threatening even the Swiss cantons, it seemed that this bandit state had done the unthinkable and actually created a formidable fighting machine. Its troops did not run away. It seemed to manufacture more and more guns; and it obviously knew how to transform conquest into workable military assets, taking money, horses, wagons and conscripts as it rolled along. James Gillray might be starting to draw caricatures literally belittling this Bonaparte as a scrawny scarecrow wearing plumed hats a size too big. But William Pitt and his intelligent, inexhaustible secretary of war, the Scot Henry Dundas, knew he was no joke. Tom Paine, for one, believed he would be the long-awaited Liberator of Britain; urging him to prepare a fleet of 1000 gunboats, he did his best to persuade the future Emperor that in the event of an invasion there would be a huge uprising, for ‘the mass of the people are friends to liberty’. Initially, at any rate, Bonaparte was impressed enough with Paine to appoint him leader of a provisional English Revolutionary Government to travel with the invasion fleet when the order was given to sail. But the order never came, Bonaparte turning his attention instead to Egypt.

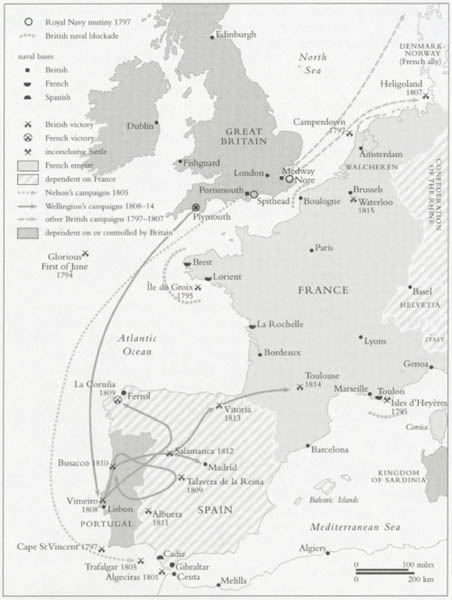

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars between England and France, 1793–1815.

The prospect of Paine’s return was not, however, high on the list of the British government’s concerns. Even before the magnitude of Bonaparte’s victories in Italy had sunk in, something happened in the spring of 1797 that did indeed seem to turn the world upside down: mutiny in the Royal Navy. The base at Spithead in the Solent, off Portsmouth, had been the first to go; then the Nore in the Thames Estuary. At one point the mutineers managed to blockade the Thames itself. Their demands were pay and the cashiering of some officers, not any kind of radical agenda. But the commonplace was that a third of the navy’s 114,000 manpower was Irish, and since Ireland had apparently become a breeding ground for revolutionaries and known agents of the French, the mutinies suddenly took on the aspect of a conspiracy. In fact, the ‘Irish third’ was a myth. Irish sailors – often the victims of impressment – numbered no more than 15,000. But even this was enough to scare the Lords of the Admiralty, who had had a frighteningly narrow escape the previous December. A fleet of 43 French ships and 15,000 troops, commanded by the general thought to be the most dangerous of all, Louis-Lazare Hoche, and the Irish republican Theobald Wolfe Tone, had been prevented by foul weather from making a landing at Bantry Bay on the southwest tip of County Cork.

Ireland was, as always, the swinging back door to Britain. Had Hoche managed to land his troops, they would have had an immediate numerical superiority over the defending British garrison of at least six to one. For a country known to be so vulnerable it was, as Wolfe Tone had correctly

pointed

out to the Directors in Paris, complacently defended. There were perhaps only about 13,000 regular British troops stationed there, who in wartime might be reinforced by another 60,000 militia. And even these estimates of the defence were based on the loyal turn-out of the Volunteer movement during the American war; since then, especially in the last few years, the political situation in Ireland had drastically changed.

If it had changed for the worse, moreover, it was largely the fault of Pitt’s own mishandling of the situation; his refusal to act on his own intelligent instincts. Since the creation of an Irish parliament in 1782, an articulate, energetic political class – both Catholic and Protestant – had been able to air its grievances against the narrow ascendancy of the Protestant oligarchy who ruled from Dublin Castle. The American lesson of the risks of imposing taxation without representation seemed even more pertinent in Belfast than in Boston. A meaningful degree of political devolution and electoral reform – not least the enfranchisement of the Catholic majority – was urged. But for all the flamboyant rhetoric of the lawyer Henry Grattan, the leader of this movement, there was no thought of a revolutionary break-away. A freer Ireland was supposed to be a more, not a less, loyal Ireland – and the hope was that George III would in fact be less, not more, of an absentee. When the French Revolution broke out, Pitt’s first thought was that the natural conservatism of Irish Catholics could be used to tie the Irish reform movement closer to Britain and make sure they did not enter some sort of unholy alliance with the nonconformist Dissenter radicals, especially in Belfast. The Dissenters’ sympathy for the Revolution was only too clear, not least from their jubilant celebration of the anniversary of the fall of the Bastille. But the precondition of a rapprochement between the Catholics and the British government was, obviously, their emancipation, or at the very least the relief of their legal and civic disabilities, limiting their rights to vote and hold political office.

It was in the mid-1790s, then, that a scenario to be repeated time and again over the next two centuries miserably played itself out. The prospect of a British government selling out the Protestant ascendancy threatened a backlash to the point of a complete breakdown of the Dublin Castle system of government. And the leaders of the ascendancy were able to use the generalized social panic spread by the Revolution – and apparently confirmed in the violent acts of armed militias, such as the Catholic ‘Defenders’ and the Protestant Peep o’ Day Boys, in Irish country towns and villages – to persuade Pitt that this was no time to be toying with liberalism. In 1795 a new Whig viceroy of Ireland, Earl Fitzwilliam, came to the point rather more abruptly than Pitt cared for, peremptorily dismissing a number of high officers of the Castle and making known his plans for a sweeping emancipation of the Catholics that would give them equal rights with Protestants. He was recalled after only seven weeks in office.

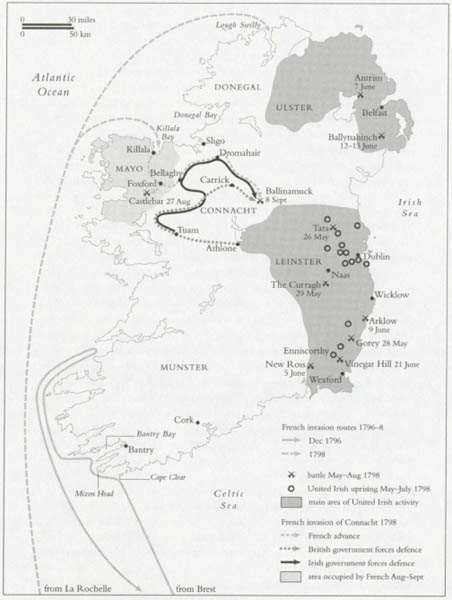

The Irish rebellion, 1798.

The removal of Fitzwilliam – however clumsy his tactics – was a true turning point in the swift downhill ride of Irish politics towards sectarian misery, terror and war. For it finally disabused the ‘United Irishmen’ – an organization formed in 1791 with many Protestant as well as Catholic members – of any remaining optimism that fundamental justice and reform would be gained from continued collaboration with the British government. Increasingly, as wartime conditions began to pinch, the question of precisely what quarrel Ireland had with

France

became voiced. Young Irish republicans like Lord Edward Fitzgerald (the cousin of Charles James Fox) and Arthur O’Connor had been in Paris invoking a connection between the two causes that went back to 1689, attempting to persuade the French government to extend its ‘liberation’ strategy of revolutionary assistance to their own country. But the conversion of Wolfe Tone, the Protestant secretary of the Catholic Committee, from a mainstream constitutional reformer into a full-fledged republican nationalist, prepared to wear the uniform of a French general, was symptomatic of the line Irish politicians were now prepared to cross to realize their dream of national self-government. Once, not so long ago, Tone had hoped to work

with

the British government to move towards autonomy. But after that government broke up the United Irishmen (forcing its members into Britain itself, to make contact with Scots and English revolutionary radicals), and following Fitzwilliam’s removal, Tone’s public utterances defined the enemy oppressor and conqueror as ‘England’.

A deteriorating military situation in Europe and a consciousness of their limited resources in Ireland meant that Dublin Castle could not afford to dispense with the help of Protestant militia – like the Orange Order, founded in 1795 – to counter Defenderism, and thus instantly aggravated the situation. By the beginning of 1798, then, the tragic spectacle of modern Irish history was already on view: rival, armed sectarian irregulars committing mutual atrocities against the backdrop of an embattled Britain fighting to close its own back door against invasion.

While the French army was encamped on the Normandy coast, Irish agents had been sent to England and Scotland to sound out the possibility of a domestic uprising in the event of an invasion. They returned deeply pessimistic, but much more optimistic about a rebellion in Ireland itself. For months, the familiar game of ‘after you’ was played out, reminiscent of the disastrous strategy used by the Scottish Jacobites during the

first

half of the century: the French waited for signs of insurrection, while the United Irishmen waited for news of a French expedition. Finally, in the spring of 1798, the Irish acted first, attacking Dublin Castle and bringing out much of the southeast in revolt. However, Ulster in the north, the key to success, remained ominously quiet. The customary atrocities were committed by both sides and at Vinegar Hill on 21 June the Irish were brutally routed by British troops, giving the new viceroy, the now aged but still vigorous Cornwallis, his last, bloodiest success in a career devoted to cleaning up the messes made by the British Empire.

French help did come, but it was too late and landed at Killala on the shore of County Mayo in the west, as far away as it was possible to be from the decisive southeastern theatre of conflict in Leinster and Munster. But the western province of Connacht

was

poor, angry and overwhelmingly Catholic. It had strong Defender support in the villages and country towns and an impromptu army, led by schoolteachers, farmers and priests, and armed with pitchforks and pikes. Connacht rallied to the French. Before the British and the yeomanry could regroup the insurgents had some success, at Castlebar; but before long their supplies of men and munitions dwindled and capitulation was inevitable. To cap the disaster, a small fleet with Tone on board, which had barely made it past the British blockade at Brest, was caught off the coast of Donegal. Tried and found guilty of treason, Tone committed suicide in prison before he could be hanged.

A bald summary of the military ebb and flow of the events of what became known as ‘the year of the French’ does not, however, properly record the magnitude of the misery of 1798. At least 30,000 Irish were slaughtered; an economically and politically dynamic world turned into a charnel house of invasion, repression and sectarian massacres – although, once the immediate military threat had passed, the government sensibly commuted many of the sentences passed on rebels. More decisively, hopes of Irish freedom were replaced by the fact, in 1801, of Irish absorption into Britain: the completion of the last cross on the Union Jack. The parliament at Dublin (retrospectively considered the root of the problem) was abolished and Irish members would now sit at Westminster. But this move was anything but a quid pro quo. The number of Irish boroughs, and so the number of representatives in parliament, was steeply reduced and the Irish debt (unlike the Scottish equivalent a century earlier) remained separate – and a serious taxable burden on the people of Ireland. Henry Grattan, who had lived through all this, was only telling the truth when he declared that the union was ‘not an identification of people, as it excludes the Catholic from the parliament and the state … it is … not an

identification

of the two nations; it is merely a merger of the parliament of the one nation in that of the other; one nation, namely England, retains her full proportion; Ireland strikes off two thirds … by that act of absorption the feeling of one nation is not identified but alienated.’