A Fighter's Heart: One Man's Journey Through the World of Fighting (37 page)

Read A Fighter's Heart: One Man's Journey Through the World of Fighting Online

Authors: Sam Sheridan

Tags: #Martial Artists, #Boxing, #Martial Arts & Self-Defense, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Sheridan; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Sports, #Martial Artists - United States, #Biography

A dog fight in the Philippines.

Paulo Filho, member of Brazilian Top Team, Brazil, December 2004.

But in the

corrida,

the matador is not exposed to physical and emotional damage by duty, or conscription—he is a volunteer, a true believer, a lover with his love. And there are no limits to love, it is quite merciless.—A. L. Kennedy,

On Bullfighting

I was lying awake in the heat and dark when the alarm went off. It was three-fifty a.m. I dressed, Tim knocked on my door, and we went quietly down the tiled halls, broad stairs, and through the lobby.

It was pitch-black and hot outside, not the roiling heat of the day but a friendly, swampy mush, the cooling sea not far off. We were on the outskirts of Pattaya, in Thailand, down near the gulf; and it was still the rainy season. The house dogs, disturbed as we left the hotel, rioted without ferocity. We clambered into the car.

Tim drove through the night, the low grass and jungle, to his farm, which was around the corner and down a rutted dirt road. We loaded Herbie into the crate after checking his weight. Herbie was dense, lean to the point of starvation, and muscular, a tawny red pit bull with a big head, a “head like a brick,” his co-owner, whom I’ll call Monty, said. Herbie was ecstatic to be off the chain, a dense ball of energy thrusting against his leash, tail lashing the air. He was an American pit bull, of course—serious dogmen wouldn’t dream of fighting anything else. Herbie was a decently bred dog, Tim knew his lineage back five or six generations, but today was his first fight, his first test. He was thought to be a good dog, if not a world beater.

Herbie was slightly above weight, a hundred grams or so, but a good shit and a piss would take care of that. “He drinks a lot of water,” muttered Tim in his broad Australian accent. “I’ve never had a dog do that. Usually, by the end, when they’re in condition, they don’t drink much.”

Tim CEK (Combat Elite Kennels, his personal group and the name he wanted me to use) was a bookish man in his early thirties, gray hair starting to belie his youthful face. He was half Thai and half Australian, and although he was perfectly fluent in both tongues, he was often mistaken for

farang

in Thailand. He was my guide to the dog world. He was the expert. He had about fifteen dogs, and he and Monty (a white British safety engineer) were co-owners of Herbie. “You’ll see yards where they have hundreds of dogs, but those dogs are all shit, and they don’t know what they’ve got. They’re just hoping to get lucky. You need to keep your yard small, with high-quality dogs, so you can understand what you have,” Tim said.

International dogfighting is a mixed bag of enthusiasts. Tim’s friend Ike X was a relaxed Asian man in his late thirties or forties who had been to Harvard and spent ten years as a cowboy in Montana. He was now basically a professional dogman. We didn’t talk about Harvard.

The weigh-in was for six o’clock. They wanted to fight the dogs early to avoid the heat of the day and also to limit the visibility to prying eyes: Dogfighting was illegal in Thailand, as it is in most places. The dogs were supposed to weigh 18 kilos, just under 40 pounds, and Tim’s opponent, Art, weighed his dog first. The dog (also an American pit bull) was meek and yellow, his tail whipped down between scrawny legs, and he weighed in at 17.9 kilos. They weighed the dog on a hanging electronic scale slung from a low beam, with a strap made from an old seatbelt cinched around the dog’s body, right underneath the forelegs. The dog hung there nearly upright, twisting idly, tail twitching slightly but otherwise still, eyes staring. He was a good-looking, friendly-faced dog with soft eyes.

The Captain, who fancied himself judge and referee (even though he was neither), was an older man of Afghan descent, a skipper in the Canadian merchant marine who had sixty years experience with dogs. He was a stickler for details, and his watch beeped urgently at six a.m. Herbie still hadn’t shat or pissed, and despite some vigorous walking, came in at 18.1 kilos. The Captain, with some satisfaction, gave Art the forfeit money.

When you agree to fight dogs, you set a weight, and if your dog doesn’t make the weight, you must pay forfeit money, maybe a quarter of the money you put up to fight, and then it is up to the opponent to decide if he still wants to fight.

The forfeit was twenty thousand baht (about five hundred dollars U.S.), and Tim was a little annoyed because he had given Art breaks before with weight; they had fought many times, and all he needed was ten minutes to get Herbie to void his bowels. Art was glad to give him more time, but Art’s partner took the money, and Tim said, “I’ll remember that.”

In the world of dogfighting, I found, there is a fanatical adherence to the rules. Honorable dogmen, good dogmen, have a very strict code of behavior, predicated on camaraderie and desire for fair play and a fair test of their dog. They look down on dogmen who are just in it for the money, trying to build a name for themselves and hyping their dogs out of proportion in order to sell pups. They are also secretive and incredibly tight-lipped, and word of mouth and reputation are everything.

The pit had been set up, the dogs were washed, and the handlers, Tim and Art, came out carrying their dogs like toddlers who had grown too big to be carried easily, legs dangling and awkward. They clambered into the pit, and huddled over their respective dogs in the corners. The pit was a simple wooden square, just a few feet high, and the opposite corners—the scratch lines—were supposed to be fourteen feet apart.

Suddenly, the moment arrives (the referee calls, “Face your dogs—release!”), and the dogs dash into each other like brown streaks, spinning around and up and down with a continuous snapping, snarling frenzy. They writhe furiously like snakes, twisting and spitting and slavering, growling like bears. Fury epitomized. Their tails are wagging, this is what they are meant to do, and they’re fulfilling their purpose, they’re

becoming.

There is blood, but the dogs don’t care, turning and pinning, fighting off their backs and then clawing their way to standing. They’re biting, and letting go, and biting again, searching for new holds, for a vulnerable spot. They feel no pain—or any pain they feel is overwhelmed by the desire to get the other dog. I know that feeling. The fight stretches to fifteen minutes, to twenty.

Tim said to me the day before, “It’s not the best dog that will win, it’s the best man. You are fighting the man, not the dog; the dog’s just a weight.” In a sense, he’s right, and the dogmen always talk about “when I fought him” as if they were doing the fighting themselves; but of course that comment was absolutely shimmering with irony. I was reminded of something Willie Pep, a great boxer, said: “I had the bravest manager in the world—he didn’t care who I fought.”

In this fight, the dogs were evenly matched, and neither one had a “hard mouth” (a big crushing bite that can break bones or rip off flesh), so the outcome would come down to conditioning. Which dogman had conditioned his animal better?

The dogs bite and bite, their mouths locking onto each other with a horrible clack and snap of fang on fang. The teeth sometimes grind together and sound as if they are breaking. Herbie is more active and a better wrestler; he often has the other dog pinned down. This isn’t necessarily bad for the other dog, as long as he’s getting good “holds,” or bites, but it isn’t really good, either (a little like jiu-jitsu). The dogs go silent, panting, and when they freeze “in holds,” their bellies work like bellows, desperately breathing to try to shed heat. Blood covers Herbie’s face and teeth, as the other dog has chewed up his jowls a little.

The sun climbs up and strokes the pit, the players, and the dogs, and their shadows leap into being on the wall. Soon heat will be a major factor. Tim and Art pace warily around the dogs, looking and whispering, “tch-ing” and sometimes asking the dog to shake once he has a good bite, to shake and break something. It is eerily quiet—the Thais murmur occasionally, and the dogs pant.

There is the first “turn” call. Art’s dog has “turned,” and they go to “scratch.” This means that Art’s dog, for a brief second, has turned from Herbie, has turned from the fight, has shown a little bit of cur. Art and Tim dive in and pluck up their dogs, “handling” them. Immediately, a voice from the crowd begins counting the seconds, and both handlers in their corners face their dogs away and work vigorously with a wet sponge, trying to cool them down. As the count nears thirty, the referee calls on them to face their dogs, and Art’s dog, having turned, has to “make scratch.” The scratch lines are fixed in the corners, and to make scratch means you let your dog go, and on his own accord he attacks the other dog (who is being held in his corner until your dog comes to get him). Art’s dog comes off the scratch line like a bullet—he scratches hard, and the Thais murmur an appreciative sound. They like that. It means nothing, really—a dog that scratches hard and a dog that scratches slowly are the same until one won’t scratch. The dog and Herbie come together in another whirling tussle.

Now that they have scratched once, every time the dogs are “out of holds” (when neither has a bite), they have to be separated, to scratch again, alternating. The handlers stay close, and each has to seize the right moment to pick up his dog so that the other dog doesn’t get a chance to sink in a free bite. I could see why the dogs can’t be people-aggressive, because if they were, in the fury of the fight they would bite the handlers. I could also see that what was important, what was critical to the fight, wasn’t the battle itself—it was the scratch. Hairsplitting definitions and measurements of courage, that’s the dog game.

At thirty minutes, the dogs are obviously tiring. Tim’s yard man, a Cambodian who’d been in the Khmer Rouge and scared all the other Cambodians senseless, is circling the pit, calling, “

Goot

boy, Herbie,” and the twenty or so people in the audience are trying to encourage their money.

Each time they scratch, Art’s dog comes hard; but Herbie just trots out from the scratch line when it’s his turn, not in a blazing dash, but with no sign of stopping, either. Monty mutters, “The tide has turned,” and then Art’s dog cries out. I watch Herbie learning as the fight goes on. He figures out where to bite, and to bite harder and longer, going after the throat more. And finally, after thirty-five minutes, he starts to dominate.

Art’s dog scratches slower, and then finally he sits down, right at Art’s feet, his tongue flapping, belly jerking. Art exhorts him, and even gives him a tiny jerk with his legs (which is illegal; you can’t touch a dog trying to make scratch), but it’s no good, and Art knows it; his efforts are half-hearted. His dog is through. Herbie is still twisting and turning in Tim’s arms to get back into the fray. Tim is utterly expressionless; you can’t tell whether he’s won or lost. Monty is thrilled—although he knew that Herbie wasn’t the greatest dog the world had ever seen, he’s still happy with him. Like a racehorse owner whose horse comes in, it doesn’t matter if it was a slow race, you have to be happy about it. Plus, he and Tim are a couple of grand richer.

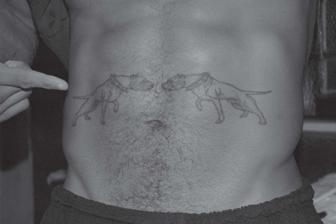

I had first become aware of the dogs in Brazil. Pit bulls were everywhere, as symbols for jiu-jitsu schools and

academías,

and tattooed on people—and not always the cartoons, sometimes photographs were rendered, like someone having his son’s picture tattooed on his arm. The first dogman I met, Escorrega, had his first dog tattooed on the inside of his arm, as did many of the other guys. As I talked to him at great length about the dogs, I started to realize

why

fighters prize these dogs so much.

The key to understanding dogfighting is the concept of

gameness.

Gameness could be described as courage, but that’s simplistic. I’ve heard gameness described as “being willing to continue a fight in the face of death,” and that’s closer; it’s the eagerness to get into the fight, the beserker rage, and then the absolute commitment to the fight in the face of pain, and disfigurement, until death. It’s heart, as boxing writers sometimes describe it, with a dark edge, a self-destructive edge; because true gameness doesn’t play it smart, it just keeps coming and coming. No matter what.

The important principle here is that dogfighting is not about dogs, or even dogs fighting, it’s about

gameness.

That’s why a dog turning is so critical, and that’s the whole point of the endless scratching: We almost don’t care how good the dog fights, the fight is just an elaborate test to check his gameness. John, a dogman in Oakland, told me, “Give me a game dog any day, a dog that bites as hard as tissue paper but keeps coming back, and I’ll take him.” Gameness was more important than fighting ability. He illustrated the idea with a story. “I was in Arkansas at a fight, and one dog was whipping the other for about fifty minutes, and at the hour mark, the dog who was winning jumped the pit wall.” John laughed uproariously. “He was mopping this dog

up,

and then he jumped the wall. I wish I still had that tape, you’d die laughing.”

I met three real dogmen—Escorrega in Brazil, John in Oakland, and Tim CEK in Thailand—and with their help I started to see how dogs and men were linked in fighting for sport. The quest for gameness in dogs is more pure, more basic, and less encumbered by illusion than the quest for gameness in men.

The capacity for violence has a direct correlation to entertainment value, which means money. Escorrega, my first dogman, had been involved with dogs for thirteen years, and he told me of prices and prizes that seemed absurd, fifty thousand dollars for certain dogs of truly spectacular proven bloodlines. A good prospect would run fifteen hundred to five thousand dollars, and good pups might fetch five to fifteen hundred. There was a dog in the United States that had generated total income of more than a million dollars, something my friends in Oakland didn’t believe but that Tim CEK confirmed, although that dog had since died. There were fights in Korea for hundreds of thousands of dollars, and tales of fights in Hawaii for a quarter million.

“Now, if you say fighting dog, you mean from the U.S. or Mexico,” Escorrega said. A pit bull (not an exact breed, but something quite specific) is a cross between the bulldog and the distinguished terrier.

“The bulldog supplies the strength, the appearance, the low pain sensitivity, the loose skin; while the terrier supplies the intelligence, heart, and gameness. Terriers are fast, strong, and smart—they can get a skunk out of a tree—and they are very, very game animals.”