A Fighter's Heart: One Man's Journey Through the World of Fighting (13 page)

Read A Fighter's Heart: One Man's Journey Through the World of Fighting Online

Authors: Sam Sheridan

Tags: #Martial Artists, #Boxing, #Martial Arts & Self-Defense, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Sheridan; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Sports, #Martial Artists - United States, #Biography

I walked into the bathroom and looked at myself, and it made me laugh; I was covered in blood, like something out of a horror movie.

As I was taking stuff off, the local paramedic came and checked me out, and he pronounced me okay, and told me not to worry about the pupils until tomorrow morning. I wouldn’t need stitches.

One of the promoters came by and said to me, “That was a great fight. Anytime you want to fight in one of my promotions, as an amateur or professional, you let me know,” and I looked at Brandon with confusion: Did he just offer me a pro fight?

It turned out I was something of a crowd favorite, basically for bleeding all over the place and standing in there and taking my licks. People kept telling me it was the fight of the night, things like that. As my eye started to swell shut, I thought, yeah, well, great. I still lost.

Monte tried to explain the weigh-in mistake as a miscommunication and hoped to make me feel better by telling me what a good fight it was, but I just stared at him. I believed him that it was an honest mistake (Monte had a bunch of other shows going on in different cities, he was working with other promoters, and he was careless), but it still annoyed me to no end. He said, “It’ll be a great story for the magazine,” and I thought,

Don’t do me any more favors, Monte.

The bottom line is that promoters don’t care about fighters; they just want asses in seats. As a fighter, you trust the promoters, and it makes you vulnerable. I think Monte just had no idea of my real abilities, and I know he didn’t know anything about my opponent. Monte figured I was working out with Pat, so I must be a badass.

The vendor gave me a free hat and T-shirt, and various people shook my hand as I drank my beer. I watched the rest of the fights and realized what a terrible venue this was; the lighting was horrible, and the white cage made it extremely hard to tell what was happening inside. Only the fighters and the ref could really tell what was happening in there, which I guess is the way it is anyway.

I chatted with my opponent, Jason Keneman, while we watched the fights and drank a few beers. He was a nice guy. He’d done some muay Thai, and this had been his first MMA fight. He hadn’t wanted to go to the ground at all, and neither had I because of my rib. The rib…after all that mental anguish, it had barely bothered me during the fight, even though he’d landed a long body shot right on it. I found out Jason had been training for four years; he had a record of 9–1 in muay Thai. I thought he had seemed pretty calm out there. My one muay Thai fight was nearly four years ago, I had been training about three months since then, and I gave up twenty pounds and had still given him a decent fight—at least I’d pushed the action. That’s what training with Pat’s guys can do for you—it can make up for a lot.

I hadn’t been knocked out or anything. They’d stopped it, and I had definitely been losing on points anyway, even though I had done some damage and had him down once. Getting my mouth guard knocked out…that’s not good. That means you’re getting the shit kicked out of you.

The dilated pupil that had frightened the EMT turned out just to be a “bruise” and was normal a few hours later. The doctor I spoke with later—who was also a fight referee—said the fight never should have been stopped. In medical terms, the mechanism of injury—a punch—isn’t going to cause the brain damage that would result in different size pupils. That would take a car accident or big fall, a more serious impact. He also gave me grief about keeping my hands up while he stitched my eyebrow (he disagreed with the paramedic).

What was most interesting was how much fun it had been. Being in there, bouncing around, pasting him, getting blasted, whatever—it had all been remarkably fun and exciting. Nothing hurt. I didn’t feel any pain at all during the fight. Sure, you know things are bad, like,

Oops, that shot was bad,

but it didn’t hurt. It was the week, the day of the fight that had really sucked. All that starving and worrying and dehydrating for nothing.

For that, more than anything, I was pissed at Monte and the show. Because I felt that if I had been fresh, and 194 pounds, and crisp…well, who knows? It would have been a better fight. As it was, I pressed the action the whole time. I chased him around. When he inadvertently kicked me in the nuts and the ref gave me time to recover, I didn’t take much because I knew my opponent was more tired than I was (I wasn’t hurt at all; the cup had worked fine). I think if I had been going strong into the third round, I might have been able to get to him. It’s all wishful thinking, but it’s the way I felt. Of course, that’s part of fighting, you’ve got to hold on to your ego, win or lose.

What embarrassed me wasn’t losing the fight, it was coming back to Pat’s looking like I got my ass kicked, even when I didn’t. My face was all swollen up, my eyes were bruised; driving back, when we stopped at gas stations, people would fastidiously avoid looking at me, like I was a burn victim. I dreaded walking into the gym because my fighting credibility was gone—I was just a journalist “having an experience.” That’s the feeling I hated, that I was playing, and I got my hand slapped for it. And no matter what people might say about how good a fight it was and that I gave nearly as good as I got, it doesn’t really matter, because without a win I felt like I besmirched the Miletich name. That’s why I didn’t put on my Miletich T-shirt after the fight; I didn’t want to associate losing with MFS. I let Pat down. One look at my face and he’d know I fought a stupid fight, that I didn’t do what I was supposed to do, which was slip and move and stay outside. It was written all over my battered face: Here’s a stupid fighter, betrayed by a stark inability to move his head.

My ribs were killing me. Sharp shooting pains. I certainly reinjured them. I found out about four months later, when I finally got an X-ray, that there was a “healing fracture” on the floating rib.

I thought about how much happier the homecoming would have been if I’d won. Sure, I was giving up twenty pounds in the fight, but Tony had done that and won. Mike French, another friend from the gym, was 147 and beat a guy who was over 190. Pat fought a guy who weighed 260. And won. That stuff just happens, especially at the amateur level in MMA.

I got out of Bettendorf fast, as I was embarrassed to be walking around the gym. I had some good friends there, but now I didn’t want to face them. I had learned a few things, like what was needed for a knockout; neither Jason nor I had put together enough punches. And that MMA is not a place to learn to fight; I should have ten amateur boxing and kickboxing fights before I get back into the cage.

It was fun. All those blows, the ribs, everything. At least I’d been in a real brawl, finally. And I hadn’t gotten killed. The fight had been stopped, I hadn’t been knocked out. Who knows what might have happened if we’d been on a desert island? I might have outlasted him in the end, all those Hills might have borne fruit.

Driving home, through a steaming Chicago, Tony called to see how I was doing. I asked him how he was doing, as he’d lost a decision in Hawaii to Matt Lindland that same night, and we had been commiserating. He was fine.

“It just sucks to lose,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said, “but there’s a lot more to it, to doing what we do, than just the fight. If the fight was all there was to it, then it wouldn’t be worth it.”

I thought about what Brandon and I had talked about at length on the drive home from Cincinnati, the meaning of

clout.

It’s not really about the admiration or respect of others; it’s about self-respect. We have an innate hatred of fear, and we climb into the cage and prove to ourselves that it is nothing to be afraid of. Even this extreme situation, this death match in a cage in front of screaming fans, is nothing to be afraid of.

After I got home Pat sent me an e-mail. He said, “I just wanted to let you know you can fly our colors anytime you want. You showed a lot of heart and 90 percent of the fighters who come here do not last as long as you did.” He closed by saying, “You are without a doubt a fighter.”

Pat Miletich said that about me.

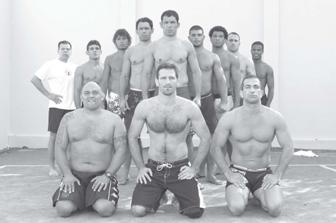

Brazilian Top Team. Kneeling, left to right: Bebeo, Murilo Bustamente, Zé Mario Sperry. Standing in the center is Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira, to his right is his twin brother, Rogerio.

At AABB Gym, Rio de Janiero. From left to right: Milton Viera, Zé Mario Sperry, Eduardo “Mumm-Ra,” Emerson “Sushiman,” November 2004.

Extravagant fictions without a structure to contain them.

—Joyce Carol Oates,

On Boxing,

referring to fighters

Rio de Janeiro is a city unlike any other, improbably built into cliffs and mountains and around the lagoons and beaches of a wild tropical forest. The urban sprawl,

Zona Norte

(the North Zone), stretches away in mile after mile of rough and vibrant city, decaying and rising from the decay. From the top of Sugarloaf, one of the rock promontories that rear like titanic fingers from the sand of

Zona Sul,

you can see everything. The sheer cliff mountains that emerge from the hotels and apartments look like God’s chess pieces. The

favelas,

the slums, have crept up the sides of the steep mountains like moss, and at night they twinkle like stars.

In the heart of

Zona Sul,

on the edge of the lagoon, Brazilian Top Team trains. They train to fight

vale tudo,

“anything goes” in Portuguese—the same thing as MMA—and Top Team is one of the most famous teams in the world.

The gym is luxurious, filling a city block, with swimming pools, tennis courts, workout rooms, and restaurants under a leafy tropical bower. The sun beats down through the giant trees and vines and cuts stark patterns on the mosaic floor. The gym, the Athletic Association of Bank of Brazil (AABB), is a gentlemen’s club, and it is an indication of the high social standing of jiu-jitsu players.

Inside the main training room, just a big padded space, about thirty men of different colors and sizes (but a similar overall powerful shape) are grappling and sweating in the tropical heat. The mats swim with sweat as bodies flow and twist against one another, sinuous as snakes. Everyone has

orelha estourada,

the wickedly cauliflowered ears of lifelong jiu-jitsu enthusiasts, and most wear multiple tattoos and knee braces. They are all training for

vale tudo

fights, but a select few are also training for Pride, the biggest MMA event in the world, held in Japan.

Martial arts have always been rife with mythology; warriors will boast, and men will make legends of their heroes, teachers, and fathers. Every martial art has its own path to victory, to invulnerability, to freedom from fear. If you study with this teacher, and practice the moves ten thousand times, no one can defeat you; you will never need to be afraid again. The secrets of the ancients, the death touch, the one-inch punch; stories of mystical teachers who can move people without touching them. It’s hard not to walk out of a Bruce Lee film feeling as if you could fight fifteen guys at once. Mysticism and martial arts go hand in hand, and every school mythologizes its instructors.

Modern MMA has been a testing ground for those myths, a stepping-off point for thousand-year-old traditions; as Pat Miletich said, “Everything gets better, cars get better, watches get better, computers…. Why should fighting be stuck in the Middle Ages?”

In the United States, before the inception of MMA, karate and tae kwon do had been dominant—fueled by the “karate boom” in the sixties and seventies, itself fueled by the chop-socky tradition of Chinese filmmaking. The highly stylized kung fu movies from China were cult fads that influenced mainstream ideas of fighting and martial arts. The Olympics had developed judo (since the turn of the century) and tae kwon do into very sporty forms and distanced them from “real” fighting. Boxing had evolved into a beautiful, elegant war of attrition.

In 1993 Ultimate Fighting, with its “no rules” cachet and promise of blood, was a pay-per-view hit in the niche market between boxing and pro wrestling. The contests were organized in part by Rorion Gracie, a Brazilian jiu-jitsu expert who was intent on bringing his family’s art and style of fighting to the United States. These

vale tudo

fights had been happening in Brazil for nearly a century, and Rorion’s slender young brother Royce Gracie, with the benefit of all that experience, won three of the first four UFCs. He won those fights by bringing his opponents to the ground and submitting them off his back—something the American audiences had never seen. The achievement was real. Royce was a tremendous fighter, and the point was not lost on the U.S. viewers: Ignore ground fighting at your peril.

Ultimate Fighting was pretty much an extension of the “Gracie challenge” that had already existed in Brazil: Bring all comers and the Gracies will defeat them. Carlos Gracie, to promote his fledgling school in the twenties, took out an ad in

O Globo,

the major national newspaper: “If you want your face smashed and your arms broken, contact the nearest Gracie jiu-jitsu school.”

When Commodore Perry opened Japan in the 1850s, Americans and Europeans were exposed to both jiu-jitsu

*

and sumo wrestling, and competition between European boxers and Japanese fighters must have existed. From the turn of the century on, Japanese wrestlers would travel to fight exhibition matches, sometimes against other wrestlers and sometimes against boxers.

“Let us link the start of

vale tudo

with the entertainment industry typical of the early industrialized world, in contexts such as Victorian London or the Belle Époque of Paris. In all these venues there were for decades challenging activities, but all that gave place to purely theatrical fights, while in Brazil real fights were practiced for all of the twentieth century, with the accompanying development of technical sophistication,” says Carlos Loddo (who is writing his own book on the history of

vale tudo

), addressing this early phenomenon.

We have all heard of those old circuses that would travel around and invite local farm boys to fight the veteran strongman (who would know all the tricks and work them over): It’s the same atmosphere in which John L. Sullivan would travel to a new town, walk into a bar, and announce, “I can lick any man in the place.” In the rest of the world, these exhibitions split into prizefighting (boxing) and professional wrestling (meaning “worked,” or fixed, fights). In Brazil, that never happened.

Mitsuyo Maeda, a Japanese fighter and ambassador for judo, came to New York in 1904 and lectured under his master, Tomita, at West Point; he had some success and continued to travel and put on exhibitions. Eventually Maeda turned to professional wrestling, “muscular theater,” in which the outcome was rarely in doubt, for money. He wrestled all over the world, in London, Belgium, Scotland, and Spain. He wrestled in Cuba and in 1909 in the bullfighting rings in Mexico City. Finally, he ended up in Brazil, with its large Japanese immigrant population, and it was there that he met the Gracie family and began teaching the young Carlos Gracie jujitsu.

Maeda taught Carlos for about five years, then left him to his own devices. That was for the best, for Carlos had grasped the ideas behind Maeda’s technique, and after being left alone, without the rigid Japanese structure, he and his brothers started to create. Carlos brought in his younger brother Helio, who was small and skinny (Carlos at first thought him too frail to train). Helio was forced to turn away from power and look for other ways to win—by attacking an opponent’s arm with his whole body, instead of pitting arm against arm. With his drive he became the chief innovator of the family. Together Carlos and Helio began Gracie jiu-jitsu, a martial art in its own right. Carlos also became interested in the connection between food and well-being, and nutrition was a pillar of his family’s success.

Ironically, it was Helio who became the big fighter out of their school, and he began achieving notoriety as he fought Americans, Japanese, and other Brazilians all through the thirties. In 1948, Helio and Carlos started their famous school in Rio, on the Avenida Rio Branca. Rio’s richest playboys trained there, and Helio’s celebrity continued to flourish. In 1950 he challenged Joe Louis to fight for a million

cruzeiros,

but Joe never accepted. Helio continued to fight, and in 1951 he fought a Japanese fighter in Maracana Stadium, the largest soccer stadium in the world. The Gracie school consisted of lawyers, judges, and the crème de la crème of Brazilian society. The Gracies were also fiercely protective of their sphere. Loddo writes that “anyone who would teach fighting in Rio, if claiming too loud that such practice was an efficient method for self-defense purposes…would end up, sooner or later, having to put the practice to test against the Gracies’ jiu-jitsu.”

Brazilian Top Team was born under Carlson Gracie, a famous fighter and teacher, and became arguably the most successful MMA team in history.

I had decided to go to Brazil to learn jiu-jitsu and meet the greatest ground fighters in the world. It was a logical step; the biggest influence on MMA in the States was without a doubt Brazilian jiu-jitsu and

vale tudo.

I would try to fill the gaping hole in my fighting; I had a little tiny bit, a glimpse of the ground game, but I needed more.

When I thought back to my cage fight, it seemed ridiculous that I had gone in there without a ground game at all. Just stupid. If I had had any kind of confidence in my ground game, I could have tried to take my opponent down when the stand-up was going all his way. It’s what Pat would have done; if you’re getting shelled standing, put him on the ground. I had gone into that fight without knowing a single takedown. Now, my stand-up was okay, good enough to spar with decent people and not come out too badly, but it wasn’t anywhere near good enough to be my only thing. I needed options; it was just foolishness not to have a complete game. If I went to Brazil, the home of jiu-jitsu, and I stayed and trained for four months at Top Team, I would

force

myself to have at least the basis for a ground game.

I also needed a way to finance it, so I somehow sold a proposal for the book you are reading. This had the added benefit of access: Now that I was a writer, I had an in with the fighters.

Brazilians fight in

vale tudo,

but the big time for them is Pride in Japan. Pride fighting, a promotion like the UFC, is big money and giant stadiums with ninety thousand people. The fighters get the respect and treatment that top professional athletes in the United States receive. Bob Sapp, an American ex-NFL lineman who fought in the K-1 (a huge kickboxing event that has branched out into MMA) and who also has competed in MMA, made millions a year and appeared on the cover of

Time

’s Asian edition and in countless Japanese advertisements. He was not a technical fighter but a monster at something like 355 pounds and 10 percent body fat—a black Godzilla—and the Japanese love him. Japan is one of the only places where MMA fighters can make serious money. The UFC, by far the dominant promotion in the United States, takes care of the top guys, but the undercard payment is brutally low.

I knew the fighters of Brazil Top Team from watching Pride fights; they were legendary, bigger than life. Zé Mario Sperry, perhaps one of the greatest ground fighters ever, led the team out from under Carlson Gracie after Carlson left Rio to come to the United States. Sperry and Murilo Bustamante, the other team leader, are among the living legends of the sport.

I was particularly interested in Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira, or “Minotauro,” as they call him, a Pride fighter who had pulled off submissions on people I had thought couldn’t be submitted. I wanted to see the modern MMA world at its apogee. I decided I would see if I could follow Rodrigo into his training and through a fight in Japan.

While training in Iowa, I had met a grappler named Danny Ives, and we had talked a little about Brazil, where he visited often. “Just come on down and I’ll hook you up,” he said. He told me about a guy named Scotty Nelson, who ran a Web site, OntheMat.com, and I called Scotty one day around three in the afternoon and woke him up.

“Yeah, man, just come on down and we’ll work it out,” he grumbled at me. So I flew down a few days later. A lesser man might have questioned the wisdom of going to Brazil to train with the greatest ground fighters in the world with a “healing fracture” on his floating rib. But not me, genius that I am.

Scott Nelson is a blond, blue-eyed California gringo who looked like a surfer kid with badly cauliflowered ears. He was thirty-five but seemed twenty-five, with a hint of the weariness and seen-it-all attitude of the seasoned expatriate, a Graham Greene character in the MTV “Jackass” tradition. He’d been in Rio for about three years, running OntheMat.com, the definitive site on jiu-jitsu in Brazil and in the States, and his Internet business supported his gringo lifestyle. He competed, as well, and had a whole bucketload of medals and honors from various competitions: gold in the 2001 Brazilian Team Championships, first in United Gracie in San Francisco (Team), third at the World Grappling Games, second at the U.S. National. He was not a top, world-class jiu-jitsu practitioner but a dedicated lifelong enthusiast, and he’d practiced, or “rolled,” with some of the best people in the world for seven years, in both the States and Brazil.

Scotty is incredibly generous and open to both foreigners and locals. He invited me to stay at his house, where there are always fighters in transition or foreigners in from the States, for a few weeks of training. When I arrived, a bunch of jiu-jitsu guys from Boulder, Colorado, were just finishing their stay, partying and chasing girls and eating like kings; they were training at Gracie Barra, the local branch of the Gracie Academy. They had nicknames like “White Rabbit” and “Green Giant.”

Scotty said I could train anywhere I wanted, as a gringo (and a beginner); but don’t talk about it, and try not to let them catch you training at competing schools. Even for foreigners, training at several different schools can be problematic. If you go from one gym to another, it is viewed as a betrayal, a stab in the back. At first this seems silly, archaic, and juvenile, but the deeper I went into the fight game, the more I came to understand and sympathize with it. The fight game consists of relationships, of reputations: between fighter and trainer, trainer and manager, manager and promoter. They all have to trust one another to some degree, and because the fight game is often involved with the shadowy edges of society, that trust is sometimes abused. There isn’t much money to go around. Reputation is life for a trainer, manager, promoter, fighter: Can you deliver the goods? If the word on the street is that you can’t, your career is in trouble. Your reputation is your livelihood and in some sense what you fight for, in all facets of the game.