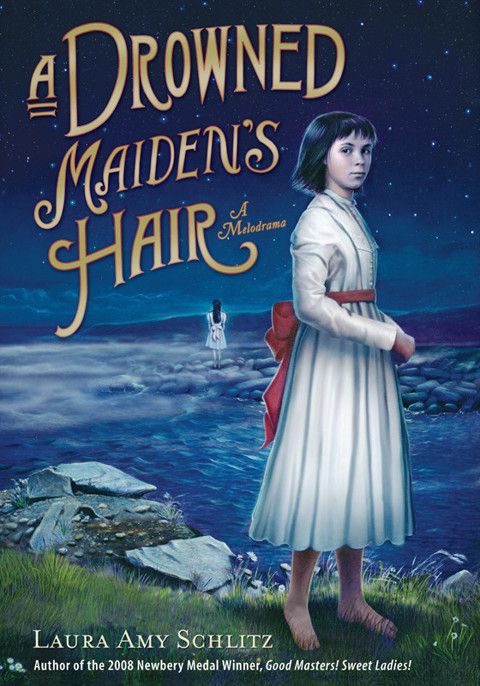

A Drowned Maiden's Hair

Read A Drowned Maiden's Hair Online

Authors: Laura Amy Schlitz

The writing of this book was made possible, in part, by a grant from the F. Parvin Sharpless Faculty and Curricular Advancement Program at The Park School in Baltimore, Maryland.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or, if real, are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2006 by Laura Amy Schlitz

Cover photographs: copyright © 2011 by Rubberball/Corbis (girl);

Copyright © 2011 by Nicoolay/iStockphoto (rose border)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher.

First electronic edition 2010

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Schlitz, Laura Amy.

A drowned maiden’s hair : a melodrama / Laura Amy Schlitz.

— 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: At the Barbary Asylum for Female Orphans, eleven-year-old Maud is adopted by three spinster sisters moonlighting as mediums who take her home and reveal to her the role she will play in their seances.

ISBN 978-0-7636-2930-4 (hardcover)

[1. Orphans — Fiction. 2. Spiritualists — Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.S34714Dro 2006

[Fic] — dc22 2006049056

ISBN 978-0-7636-3812-2 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-7636-5215-9 (electronic)

Candlewick Press

99 Dover Street

Somerville, Massachusetts 02144

visit us at

www.candlewick.com

“O Mary, go and call the cattle home,

And call the cattle home,

Across the sands of Dee.”

The western wind was wild and dank with foam,

And all alone went she.

The western tide crept up along the sand,

And o’er and o’er the sand,

And round and round the sand,

As far as eye could see.

The rolling mist came down and hid the land:

And never home came she.

“O is it weed, or fish, or floating hair —

A tress of golden hair,

A drownèd maiden’s hair

Above the nets at sea?”

Was never salmon yet that shone so fair

Among the stakes of Dee.

They row’d her in across the rolling foam,

The cruel crawling foam,

The cruel hungry foam,

To her grave beside the sea.

But still the boatmen hear her call the cattle home,

Across the sands of Dee.

O

n the morning of the best day of her life, Maud Flynn was locked in the outhouse, singing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

She was locked in because she was being punished. The Barbary Asylum for Female Orphans was overcrowded; every room in the wide brick building was in use. There were few places where one could imprison a child who had misbehaved. The outhouse was one such place, and very suitable for the purpose, because the children hated it. Though the janitor scrubbed it clean every day, it stank; the single window was high and narrow and let in just enough light to show that there were spiders. Maud boasted that she was not afraid of spiders, but she was no happier than anyone else when she sat on the high bench, feet dangling, and wondered whether any of the itches she felt were spiders creeping over her skin.

She finished the first verse of the song and began on the chorus. The outhouse was chilly, and singing warmed her blood. It also served to advertise — to anyone who might be passing by — that the spirit of Maud Flynn had not been broken. Maud had a hazy idea that the Battle Hymn had something to do with war and slavery. She felt that by singing it she was defying authority and striking a blow against the general awfulness of the day.

Two maiden ladies, the Misses Hawthorne, were coming to the Barbary Asylum to adopt a little girl of eight or nine years: Maud was eleven and therefore ineligible. The three girls who might be chosen — Polly, Millicent, and Irma — had been given what Maud considered unfair privileges. They had taken hot baths the night before, though it was neither Wednesday nor Saturday, and their hair had been put up in rags for curls. The newest of the blue houndstooth uniforms had been washed, mended, and starched, so that they might appear to advantage. As a result, the three little girls were as curly, clean, and splendid as the Asylum’s scant means could make them, and they put on airs — Maud told them so — that were perfectly sickening. Maud’s hair was thin and wispy; under no circumstances would it curl.

So Maud began the day in a frenzy of jealousy, and the proximity of the three candidates only served to inflame her further. Maud was small for her age, so small that she shared the third-grade desks with Polly, Millicent, and Irma: she had tweaked Millicent’s curls and kicked Polly when Miss Clarke was reading the morning prayer. Irma was out of reach, but Maud made herself as disagreeable as she could, glaring across the aisle and snorting when the younger girl made a mistake in arithmetic. During the history lesson, Maud disrupted the class by swinging her feet back and forth, so that the toes of her boots scraped against the floor. It was not a loud noise, but it was irritating. When Miss Clarke told her to stop, Maud gazed at the teacher with half-shut eyes and went on swinging her feet.

That had been too much. Miss Clarke was neither cruel nor even very strict, but she could not allow a child to defy her before the whole class. She swooped down the aisle and seized Maud by the forearm. Maud’s heart pounded. She knew she had gone too far, and punishment was bound to follow. She hoped she would not cry before the others.

When Miss Clarke took the key to the outhouse off the nail, Maud almost laughed with relief. She did not like being locked up in a dark smelly place, but she had been locked up before; she knew she could bear it. She also knew that her imprisonment would be brief. Sooner or later, some child would need to use the outhouse, and Maud would be set free. She braced herself against the yanking of Miss Clarke’s arm and raised her chin defiantly. One of the schoolroom windows looked out toward the yard. If any of the girls were watching her, they would see her go down fighting.

All that had happened an hour ago. Maud shifted on the wooden bench and hugged her arms. Outside, it was windy; inside, it was drafty and very damp. When Maud stopped singing, she began to shiver. She wondered if the Misses Hawthorne had arrived yet and which of the girls they would choose. Probably they would take Polly; Millicent was prettier, but her father had been a drunkard; Irma, mysteriously, had never had a father at all. Maud did not understand this, but she knew that the girls’ fathers would be held against them. No doubt Polly Andrews would be chosen: Polly, it was said, came from a good family; Polly was a dutiful little girl, conscientious about her chores, and the best speller in the Asylum. Maud ground her teeth. She detested Polly. She opened her mouth and started the chorus again, letting her voice ring out like a trumpet. “Glory, glory, hallelujah —!”

“Little girl!” chimed a voice from the other side of the outhouse door. “Little girl, why are you singing in there?”

Maud froze. The voice was unfamiliar. The idea that a stranger was listening was somehow frightening. She stared at the crack of light that framed the door. She did not breathe.

“Little girl,” coaxed the voice, “don’t stop! Go on with your song!”

Maud considered the voice. It was high without being shrill, with a queer lilt of music in it. Maud, who had heard very few beautiful voices in her life, had no hesitation in judging it beautiful. After a moment, she ventured, “Who are you?”

“I’m Hyacinth,” answered the voice, clear as a bell. “Who are you?”

Hyacinth. Maud had an idea that a hyacinth was a flower — not a common flower like a daisy or a rose, for which anyone might be named, but something more exotic. She analyzed the voice again and decided it sounded young, but grown-up. Inside her mind a picture of a young lady took shape, her hair just up: rosy cheeks and a white lacy dress and a pink parasol with fringe around the edges.

“Who are you?” repeated the voice. “Why were you singing?”

“I’m locked in,” said Maud.

“But why are you locked in?”

Maud ran through a number of possible answers and discarded them all. “It’s cold,” she stated, “and singing warms me up. That’s why I was singing.”

She listened for an answer and heard, instead, the sound of the key in the lock. The crack of light widened, the door opened, and Maud tumbled out, blinking like an owl in the spring sunshine.

She saw, with disappointment, that the stranger was not young at all. In fact, she was old: her hair was white, and her skin was lined. At second glance, Maud’s disappointment was less acute. The stranger was erect and dainty, like an elderly fairy. She wore a plum-colored suit made of some lustrous fabric that had a pinkish bloom to it; her waist was snow white and frothy with lace. At the collar, there was a gold brooch studded with amethysts and moonstones. Maud had an instinct for finery: the lace, the jewels, and the purplish cloth were all things to be coveted. She felt a surge of fury. She had no such things, and no chance of getting them.

“Who locked you in?” asked the stranger. “Was it some hateful big girl?”

Maud grimaced. She could tell from the phrase “big girl” that the stranger had made a common error. “I’m a big girl myself,” she informed the stranger. “I’m eleven.”

“Eleven!” The lady named Hyacinth clasped her hands. “You aren’t, really!”

Maud clenched her teeth. “I am,” she asserted, rather coldly. “I’m small for my age, that’s all.”

The lady had stopped listening. She was staring at Maud almost fiercely, as if something had just occurred to her. “Eleven,” she repeated.