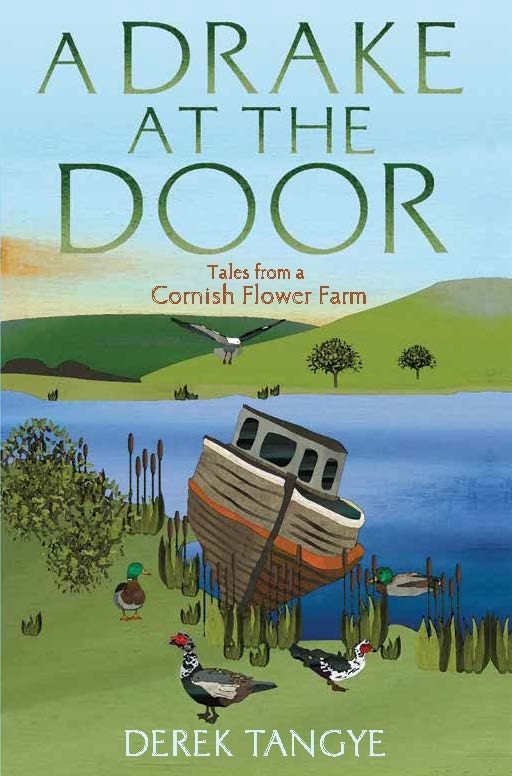

A Drake at the Door

Read A Drake at the Door Online

Authors: Derek Tangye

Derek Tangye

(1912–1996) was the author of the much-loved books that collectively became known as The Minack Chronicles. They told the story of how he and his wife Jean left behind their cosmopolitan lifestyle in London to relocate to a clifftop daffodil farm in Cornwall. There they lived in a simple cottage surrounded by their beloved animals, which featured regularly in his books. In their later years, the Tangyes bought the fields next to their cottage, which are now preserved as the Minack Chronicles Nature Reserve.

Also by Derek Tangye

A Gull on the Roof

A Donkey in the Meadow

A Cat in the Window

Derek Tangye

Constable

•

London

Constable & Robinson Ltd.

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Michael Joseph Ltd., 1963

This edition published by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2014

Copyright © Derek Tangye, 1963

The right of Derek Tangye to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-47210-992-7 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-47211-025-1 (ebook)

Printed and bound in the UK

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Cover design by Simon Levy

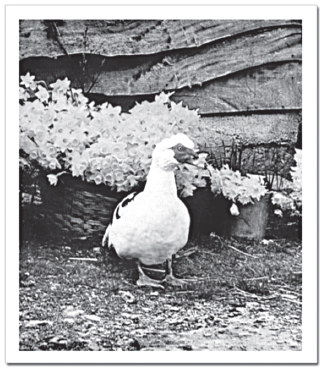

Boris, the Muscovy drake, during daffodil season at Minack

Shelagh, Jane and Jeannie in a Minack daffodil meadow

Hubert when he was king of the roof

Shelagh and Bingo outside her caravan

Jane, after winning a First Prize at Penzance Flower Show

Boris, the Muscovy drake, during daffodil season at Minack

I heard one day that my neighbour was leaving. We had been neighbours for seven years and, in view of the manner of our coming, conflict between us was perhaps inevitable. The neighbour represented the hard-working peasant, Jeannie and I the up-country interlopers.

Minack and our six acres of land belonged to his farm, although in reality it was not his farm. In the years before the last war, farms in West Cornwall were difficult to let and landowners were thankful to dispose of them under any conditions; and the conditions were sometimes these:

A prosperous farmer would rent an unwanted farm, stock it with cows, put a man of his own choosing called a dairyman into the farmhouse, charge him rent for each cow, and then let him run the farm as he wished. My neighbour was a dairyman.

Both of us, then, paid rent to the same absentee farmer; my neighbour for twelve cows, myself for the primitive cottage and the derelict land I was allowed to have with it.

On a practical basis I had the worst of the bargain. It was a whim that led us to Minack; an emotion that made us believe the broken-down cottage edged by a wood and looking out on Mount’s Bay between Penzance and Land’s End, could become our personal paradise. And after seven years I still did not possess a scrap of paper which proved our legal right to the tenancy.

The reason for this dilatoriness was fear on our part. When in the beginning we pleaded for Minack, the absentee farmer clearly did not mind whether we had it or not. We had to nudge our way into his good humour. We had to be as careful as a ship in a minefield. One false move, a word too thrusting, a suggestion too bold, and we would have been retreating from his presence without a hope of return.

This was an occasion, we both felt, when logic or the legal mind would be a hindrance. It was not the moment to bargain or be too meticulous in wrapping the deal in legal language. We wanted Minack and in order to secure it we had to appear foolish. The result was no lease, all repairs and improvements without prospect of compensation, and six acres of scrubland which most people considered unsuitable for cultivation.

And there were other snags. There was the barn, for instance, within a few yards of the cottage, which belonged to my neighbour and not to Minack. Here he used to stable his horses, collecting them in the morning and returning them in the evening; and in wet weather when no outside work could be done he would clear the muck from the floor and pile it beside the lane which led up to his farmhouse a quarter of a mile away.

We had made this lane ourselves, opening up again an ancient one by first cutting away the brush which smothered it; for when we first came to Minack the only means of reaching the cottage and the barn was by crossing two fields, waterlogged in winter.

In the autumn my neighbour used to spend days at a time in the other half of the barn ‘shooting’ his potatoes for January planting in his section of the cliff; and if it were a period when we were not on speaking terms Jeannie and I found it irksome.

‘Did he say anything this morning?’ I would ask Jeannie if she had seen him first.

‘Not a word.’

Of course, there are some who say that the Cornish resent any ‘foreigner’ who comes to live among them. I am Cornish myself and I do not believe that such resentment, if it exists, is confined to the Cornish alone. Most countrymen if they live far from an urban area are on guard when a stranger appears in their midst. Strangers represent the threat of change, and change is the last thing the true countryman wants. He views the city from afar and is not impressed by its standards; and when in the summer the inhabitants disgorge over the countryside, a leavening of them always confirm the countryman’s worst suspicions. The Cornish for the most part heave a sigh of relief when the holiday season is over and Cornwall belongs to them again.

As for individuals, the Cornish have the same basic ingredients as everyone else, the same kindliness or meanness, good humour or jealousy. It is only in obstinacy that the Cornish excel. If a Cornishman senses that he is being driven into taking a step against his freewill nothing, not even a bulldozer, will make him budge.

So our neighbour was leaving. He was forsaking his job as a dairyman to take over a farm of his own. He had won promotion by his hard work, while we now had the chance to take over not only the barn, but also those fields and cliff meadows adjacent to our own which were essential for certain expansionist plans we had in mind. We were delighted. Here was the opportunity to put sense into our life at Minack, to regularise our position by securing a lease, to act indeed in a practical fashion. It was not, however, a question of expressing a desire, and the desire materialising without more ado. We soon discovered there were complications.

The news of my neighbour’s coming departure speedily spread through the neighbourhood, and young men began tumbling over each other in efforts to gain the vacant dairymanship for themselves.

The lure, in particular, lay in the cliff meadows which were renowned for the earliness of their potatoes and daffodils. Most of these were as steep as those we had cut in our own cliff, and I did not fancy them very much myself . . . we had enough hand labour already, turning the ground in the autumn, carrying down the seed potatoes, shovelling them in, shovelling them out, carrying the harvest hundredweight after hundredweight up the cliff again. And in any case I sensed the golden days of Cornish new potatoes from the cliff were over.

But there were other meadows cresting my neighbour’s cliff that were ideal for our needs, large enough for a small tractor, and accessible to the Land Rover when it was necessary to use it. This was reason enough why we wanted them, but there was another.

These meadows were reached by passing in front of the cottage and taking the track towards the sea which led also to Minack meadows. We had watched our neighbour for seven years using this thoroughfare and we did not want to see anyone else doing the same. Minack, in substance, was remote from any habitation, breathing peace in its solitude, and we wanted to eliminate any prospect of enduring again the grit of friction.

And there were the fields around us. Had we been able to wave a magic wand we still could not have made use of all of them; but there were four surrounding Minack which, if we possessed them, would provide the twin advantage of isolation with the practical one of giving us the elbow-room vital for development.

In particular we needed flat ground for greenhouses. We already had one small greenhouse tucked in a clearing of the wood and another, a splendid one a hundred feet long and twenty-one feet wide, stretching down in front of the cottage on land that was swamp when we arrived. We felt sure that our future security lay in such factory-like protection; the only way possible to demolish the omnipotence of the weather.

We were aware, then, that we were at a crucial moment of our life at Minack. Here we were poised between stagnation and progress, an irritant and solace; and the success or failure of the action I was about to take would dominate the years to come. I had decided to be bold.

The absentee landlord had by now become a good friend of ours.

‘Harry,’ I said to him one day, ‘how about your giving up the lease and letting me have it instead?’

I knew quite well that by making this overture I was heading for a period of bargaining. He belonged to the breed who prefer this period of bargaining to its culmination; and should it be a horse he was buying, or a motorcar or a load of hay, his ultimate pleasure lay in the skill with which he had conducted the negotiations. I, on the other hand, like to get a deal over as quickly as possible. I have not the nerve of a dealer. If I know what I want, I find no pleasure in protracting negotiations provided the sum is reasonably within the figure I have decided to pay.

Nor had I, as far as these negotiations were concerned, any cards up my sleeve. I was living again the time when I first asked Harry for Minack. I had to have it, and he knew it. I was naked. I was at his mercy.

Inevitably he began to dally; and, as if I were a fish on a hook, he set out to give me plenty of line and himself plenty of play before he landed me neatly on the bank. Out came the excuses . . . he had promised the farm to Mr X . . . it had been for so long in his family that for sentimental reasons he did not wish to give it up . . . if Mr X did not have it, he would use the fields for young cattle . . . and so on. All these proposals were told with such conviction and friendliness that I would come back to Jeannie in despair.

‘He won’t let us have it,’ I would say to Jeannie disconsolately.

It was the mood that Harry wanted to create. He knew that, keen as I was to do a deal, he could titillate me to be still keener. I

had

to buy the lease from him, and each fruitless interview only made me more frantic; a cigarette dangling from his lips, he watched me betraying my anxiety.

Meanwhile a corner of my mind was occupied by another problem. When, and if, Harry and I came to terms I would find myself a tenant not only of Minack but also of the hundred-acre farm to which it belonged.

This was absurd. I had been consumed to such an extent by the desire for self-preservation that I had ignored the implications the success of my endeavour might entail. And anyhow, would the landlord accept me as a tenant?

The landlord was a remote person who owned large estates in Cornwall and who, as is customary, employed a land agent as a buffer between himself and his tenants. He was an enlightened landowner and he possessed a zeal to preserve the countryside, not to exploit it; in particular he felt a special trust for the wild, desolate coastline where Minack was situated. His tenants were, of course, carefully chosen and his farms well managed but, and this was the key to the situation as far as I was concerned, the Minack farm was the only one on his estates which was now leased to an absentee farmer.