A Blaze of Glory (6 page)

When Beauregard began to submit elaborate plans for strategy that stepped squarely on the toes of Davis himself,

grand plans

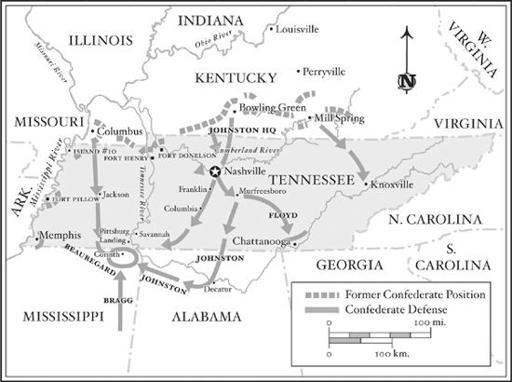

that Beauregard insisted were the only way the war could be won, Davis’s patience ran out. Beauregard was ordered to the West, assigned to some vague position in a theater of operations that had already been assigned to others, Albert Sidney Johnston in particular. Johnston didn’t have any particular hostility toward Beauregard, assumed that since the man was from Louisiana, he might assist in drawing troops out of those areas that had been reluctant to send their men off to fight in Tennessee. With the defeats at Henry and Donelson, and now, with the strategic need to pull the Confederate troops southward from Kentucky and central Tennessee, Beauregard’s talent for organization seemed, to Johnston at least, to be an asset. If Beauregard was given any reason to believe he had been sent westward to replace Albert Sidney Johnston, Johnston had heard nothing of the sort. Johnston couldn’t help wondering if the fiery and outspoken Creole was truly willing to accept a subordinate position in anyone else’s command.

Beauregard quickly established his headquarters at Corinth, Mississippi, and for good reason. With most of Tennessee completely vulnerable to the far more numerous Federal forces, Corinth, situated just south of the Tennessee border, anchored the next most essential defensive line. The town had been created by the junction of two major rail lines, the north-south Mobile & Ohio line, and the east-west Memphis & Charleston line. The east-west line in particular was crucial for the South to maintain a supply and communication link from the Mississippi River all the way to the Atlantic coast, and no one in the army, nor in the Confederate capital, faulted the strategy that called for a stout defense of the railroad. Corinth was even more valuable to the Federals, since the railroad could carry their own troops and supplies southward, from the Ohio Valley to the Gulf Coast.

JOHNSTON ABANDONS KENTUCKY;

THE CONFEDERATE ARMY WITHDRAWS SOUTHWARD TO CORINTH

Beauregard’s arrival at Corinth had initiated even more calls for troops, urgent orders for any forces along the Gulf Coast not presently threatened to move rapidly to the rail center. Other troops were summoned from the west, troops who had been fortifying outposts closer to the Federal positions in Louisiana and Arkansas, that might be in danger of being cut off altogether. More troops were pulled in from the east, from various outposts in Alabama. While no one knew exactly what the Federal commanders were planning, it was certain that the coming of spring would mean movement, and Beauregard and Johnston agreed completely that the most likely targets would be Corinth or possibly Chattanooga. To throw misdirection at the Federal spies and cavalry patrols who might be observing Johnston’s troop movements, General John Floyd had been given twenty-five hundred troops and ordered to march noisily from Murfreesboro to Chattanooga. In addition, Johnston himself had made indiscreet mention around his headquarters that his own movements, and the movement of his remaining troops at Murfreesboro, would be toward the south and east. The goal of the deceit was twofold. If the Federal command intended to target his army first, Johnston hoped to convince the Federals to charge off in the wrong direction, a lengthy jaunt toward Chattanooga. The delays that could cause in the Federal advance would allow Johnston time to improve the fortifications around Corinth. But, more likely, if Halleck intended to seize the rail center after all, it could be enormously helpful if the Federal generals were convinced that most of Johnston’s troop strength had marched off elsewhere.

O

n February 28, Johnston’s columns began their march southward, evacuating Murfreesboro, filling the roadways that led first toward Shelbyville and Fayetteville, Tennessee, and down across the Alabama border toward Huntsville. Though the invectives still poured his way, harsh condemnation from civilian leaders in Tennessee and throughout the Confederacy, Johnston focused more on what it would take to assemble an army with sufficient size and strength to push back at the Federal troops that were already slicing Tennessee in two. No matter the validity of the criticism, or how vicious the wrath of the newspapers and politicians in Richmond, Johnston knew that ultimately, those words did not matter. There was one way to renew the spirit of the people, of the army, and of his own command: assemble an army strong enough to confront the enemy, and then destroy him.

SEELEY

NEAR THE DUCK RIVER, CENTRAL TENNESSEE MARCH 19, 1862

F

or long miles the roadways were nearly impassable, the travel miserably slow, rivers of mud deepening by the hour from the steady rain. There was no real alternative to the roads, the horses unable to maneuver at all through the dense thickets that lined most of the countryside. There were breaks in the thickets, open grassy fields, but there was risk there, the rain so intense that a short jaunt across a mile or more of roadless countryside might get them lost. Worse were the farmlands, not yet planted, so that the muddy fields were deep and soft, and could swallow the legs of their horses, a nasty potential for crippling injury to their mounts no cavalryman wanted to confront. Regardless of the weather, the farms themselves could be a threat of a different kind, and it had surprised Seeley to hear the colonel’s briefing to beware the citizens, farmers, and shopkeepers. None of the horse soldiers expected to learn that even in Tennessee the civilians were not always friendly, did not necessarily support the army and their cause. Forrest had cautioned them that spies could be the most innocent to the eye, offering the friendly conversation, or the generosity of a pail of milk, a basket of eggs. The loyalty to their army was not guaranteed even from people whose homes the army claimed to protect, and more than once the cavalry had found a local man with maps in his pocket, showing troop movements, identifying regiments and their commanders. There was no good reason for any civilian to be carrying that kind of information, and the men who had been caught had almost always been traveling north, where the enemy waited for any information they could receive. It had infuriated him, all of them, to find that these good people whose homes lay firmly in Southern territory might not believe in the cause that the soldiers were willing to die for. And so, riding through the misery of the awful weather there could be no visits with civilians, no matter how tempted they were by the dry barn, the promise of temporary shelter. The mission was too critical and these men too few to be given up by a turncoat farmer who had some link to a Yankee spy with a fast horse.

The rain had been relentless, a long day made longer, and Seeley had guessed it to be after four o’clock when the captain had finally ordered them to stop. Captain McDonald had moved out from the column, taking Seeley with him. They were the only two officers in the troop, and McDonald had dismounted, leaned in close to what made for a dry place beneath a towering oak tree. There the captain had unrolled a map, had shown confidence that their objective, the Duck River, was close in front, but that meant that the road they were using was far too dangerous. The order to dismount had gone to the others, the horses led by their reins into the dense woods, what quickly became a swamp. In a small muddy clearing, one-fourth of the men had been designated to remain behind, to take hold of the horses, keep them in tight groups. It was always the precaution, that on a mission like this the men were too few to fight any kind of skirmish. The order had come the day before from Forrest: There would be no engagement at all, no matter what enemy they might find. The information McDonald’s men were seeking was far more valuable than any results that could come from a firefight. With the men on foot, the shotguns had stayed behind as well; no need to carry the extra encumbrance. The men had grumbled about that, but in the swamp, slow going through deep muddy bog holes, the weapon was a liability and likely would be made useless by the mud that quickly engulfed them all. If there was comfort to be had from a weapon, they all carried the heavy knives at their belts.

The mud was deep and cold, the going too slow and too difficult for anyone to waste energy by complaining. They had already been soaked through their rain gear and whatever uniforms they might have, the exercise of crawling over and through the thickets at least helping to warm them up. As if to add to their misery, the wind grew stronger, the rain harder still, the sharp breeze driving the rain into eyes and ears.

They were spread out within close sight of one another, still moving forward, led by the compass of the captain. Seeley watched him, was suddenly grabbed, wrapped by a thorny vine, hung up by the ropelike strength. He tried to pull free, no strength in his legs, too much in the vine, and he reached for the knife at his belt, felt a hand on his arm, soft voice.

“No. Untangle it. Just step out of it. Knife won’t cut this stuff.”

He saw the face, muddy wetness beneath the eyes, Sergeant Gladstone, older man, something of the swamps that seemed to be a part of this man even in the best weather. His legs worked themselves free, Gladstone not waiting to be thanked. Seeley found the captain again, moved that way, mud still sucking at his boots, one man nearby stumbling, hands down in a soft pool, mud up to the man’s chest. Hands helped him up, a curse echoing softly through the rain, but still they moved forward.

It seemed to be getting darker, but Seeley knew not to gaze upward, that eyes full of rain told you nothing. The downpour continued, the wind driving the rain through the trees like a flowing curtain. Fat streams and drops from the limbs above seemed always to find Seeley’s collar, even the rubberized raincoat not keeping him dry. But no matter the weariness, Seeley kept that one sharp place in his mind, what kept the eyes focused, staring ahead. There was after all a purpose to this, that somewhere out there, an enemy might be waiting, and even if the Yankees were huddled blindly in this same misery, the men knew what Captain McDonald was trying to find, where this swamp must surely lead. Seeley did as they all did, felt and probed his way through the thickest places, the small openings usually holes of deep mud, and so the going was painfully slow. But the men who had groused loudest about leaving the shotguns behind were as calm and miserable as the rest, and even as they searched for some sign of an enemy, Seeley was utterly convinced that no other human had ever crushed their way through this swampy hell, wet or dry.

His boots were completely full of water, the mud growing thicker on his pants legs, like wax on a candle wick, heavier, denser with each step. He kept his eye on the captain, saw a change now, McDonald holding up a hand, dropping to his knees, peering through a thicket of low cedar trees. Seeley froze, fully alert, and the captain made another motion with his hand, pulling the others down low. Seeley crept forward, close beside McDonald, followed as the captain pushed slowly into the cedars. His heart was already pounding, exhaustion, but there was excitement now, and he had to see, ignored the hard chill of the water now pushing up above his waist. McDonald glanced back, another wave of his hand, holding the others in place, all of them on their knees, settling into the mud. If there were curses about that, Seeley heard nothing but the rain. He took a long breath of soggy air, watched the muddy faces, most of the men disguised completely by the filth that covered them. His eyes were filled by a gust of blowing rain, and he wiped by instinct, too quickly, his fingers too dirty to help. McDonald waved them forward, his hand giving the signal,

slowly

. Seeley watched them, no gripes now, respect for the captain, all of them knowing something dangerous might be very close. He looked again at McDonald, who turned away, satisfied his order was understood. When the captain began to crawl, the others did the same, pressing through the dense cedars, thick curtains of water on the tangle of branches. As they moved past the brush, they all saw what the captain saw. A few yards beyond the cedars was another low thicket of brush, and beyond that, the Duck River. Now they could all see why they had come, what this miserable mission was about. On the far side of the river was a single mass of blue.

McDonald turned his head slowly, scanned them all, nodded, another motion with his hand, the signal to stop, to lie flat. No one spoke, used only their eyes, the men gathering closer, in line behind the low cover of the brush. Seeley did his job, made sure they were spread out, glancing across the river with every breath. The rain was driving even harder now, a deep rumble of thunder somewhere above, and McDonald grabbed his shoulder, a hard hiss in his ear.

“We got lucky, Lieutenant. Right where they’re supposed to be!”

Seeley guessed the river to be two hundred yards across, saw it was thick and muddy, noisy splatters by the rain, the current flowing by in a storm-fueled rush. Some fifty yards to one side were the remains of a railroad bridge, charred stubs of thick logs and stone, the bridge eliminated days before by the good work of other raiders. The Confederate cavalry had patrolled these roadways and river crossings for weeks now, doing as much damage as they could, most of them not having to fight weather as bad as this. The orders had come to all the cavalry units, that as the bulk of the army marched away from Murfreesboro, the bridges behind them were a priority, and so every effort had been made to cut any transportation lines that would allow the enemy to pursue.

McDonald looked toward his men, another signal,

sit tight

, and he peered up carefully through the brush. He turned toward Seeley, motioned him closer, and Seeley crawled that way, fought the wet goo thick in his pants, the stinging in his knees. McDonald pointed.

“Those two. Watch ’em.”

Across the river, on a bluff a few feet above the water, two men rode close, high on horses, their uniforms disguised by black rain gear, but there was no mistaking their authority. Words were passed, arms waving, pointing, hot tempers, someone not afraid to show his anger. Behind them the uniforms were not disguised at all, dense rows of men in blue, spreading away into a clearing. Seeley saw it clearly now: An entire column of Federal troops had reached the place where the trail led to the remains of the railroad bridge, their officers no doubt discussing just what they were supposed to do next. Quickly, more men on horseback were gathering, a dozen now, some of them aides, limp flags hanging from crooked flagstaffs. Arms were pointing, and even through the rain Seeley caught a flicker of voice, a shout, obvious anger. Suddenly two foot soldiers waded out into the river, straight toward the crouching cavalrymen. Seeley felt a burst of heartbeats, put a hand on his knife, but the men waded out only a few yards from shore, were already waist-deep, struggling against the current, and just as quickly, they pulled themselves back to the others who watched from the bank.

McDonald reached out, patted Seeley on the shoulder, silent joy, and Seeley knew the meaning. Too deep to cross, too much current. The bluecoats would have to find another way. The Confederate cavalrymen that had come before them had done good work, and Seeley had been told already what the enemy commanders were learning themselves, that for miles in both directions, the Duck River was just as he saw it here. If the Yankees intended to cross anywhere near this part of the river, they would have to build their own bridges.

McDonald raised field glasses, studied, said, “Look for the flags. Try to see some detail. We need to know who these people are.”

Seeley pulled his field glasses out of his coat, mud coating the lenses, and he smeared a finger frantically, cursed to himself, hoped McDonald didn’t see. McDonald said, “Nothing they can do right now. They’ll have engineers come up, probably supposed to be there already. Bet that’s why that officer is so hot. He’s probably in command, bet he’s a damn general. And hot as a hornet. I’d love a chance to pick him off. Good musket would knock him right off ’n his horse. Never know what hit him. Maybe I’ll get you some other time, General Whoever You Are. Just wish I could see your damn flag, division, regiment, anything.”

The captain paused, studied again with his field glasses, shook his head.

“Can’t make out a single damn flag. Those bluebellies marched up here all full of piss, ready to grab General Johnston by the tail, and I bet that general over there was told the river might be shallow enough to ford. Not even generals can stop the rain. Looks like they’re gonna have to just sit here, probably build a bridge. Otherwise, they’re gonna have to wait for the water to drop. That could take a couple weeks.”