A Blaze of Glory (40 page)

PRENTISS COLLAPSES

T

he word had come from the officers that something new was happening across Duncan Field. As he rode forward, he passed by the men who had held the line, could see the weariness, the worn faces, dirt and spent powder coating every man. Many of the wounded had been taken away, but many more had not, and they mingled with the dead, with troops who had taken the worst the enemy had given them, shattered bodies, pieces of men cut apart by artillery. Others lay where the musket balls had found them, some with no weapons anywhere near them, those muskets now in the hands of others who fought close by. The line was thinned as well by those who were gone, not wounded, but panicked, some of the men enduring as much as their courage would allow, the continuous assaults finally besting them. As he moved forward, the men who were left were watching him, empty stares, no cheers, no one seeming to care that their general had come up to see what it was that had so caught the attention of those few lieutenants who still stood with their men.

He had left the horse behind, moved out toward Duncan Field with binoculars in his hand. Down to one side was a burned thicket, peppered with the charred bodies of men. Some of the grassy patches remained but not many, most of the cover obliterated by the advances of the enemy or by the swarms of musket fire that had sliced and chopped and ripped through any vegetation that rose up in the way. The officer who had led him forward had fallen back, and Prentiss looked behind him, saw the man drop down, slumping against the ragged stump of a fat tree, the man’s energy gone, his duty performed. Behind Prentiss, an aide stayed close, a young sergeant who seemed to absorb with a growing terror all that lay around him. Prentiss said nothing to the man, had seen too much of this himself, and by now he didn’t care if the sergeant ran away or not. Prentiss stepped forward over every kind of obstacle, was surrounded now by men with muskets, some sitting with their backs to the enemy, most in some kind of cover, stumps and broken timber, all that remained of the stands of hardwoods. Some curled up in man-made holes, dug with bayonets, seemed paralyzed with exhaustion, some of them actually sleeping.

He reached the wagon trail, saw a fence line where rebel soldiers had fallen, some bringing down the fence rails where they fell. Some of his men were using those bodies to form their own wall, leaning against stacks of rebel corpses, protected now by sacks of dead flesh. The smoke had drifted away, and Prentiss knew it had been nearly an hour since the last attack on this part of the line. But still the stink was there, artillery, spent powder, churned soil, and then, something different, unfamiliar, the astounding stench of burned corpses, those lumps of black in the charred grass, one fire that had kept thankfully to the far side of the wagon trail. To the right, the ground dipped down, and he saw bodies strewn across a creek bed, some his own men, many others the enemy, one officer in gray, the man’s sword still in his hand. Prentiss was in the trail, felt no danger, no reason to duck low. The field was strewn with bodies, some moving in a slow crawl, no one on his side of the line seeming to care. He raised the glasses now, searched the far woods, what the officer had told him to see. He expected nothing at all, just an exhausted soldier’s imagination, blinked through the lenses, struggled to focus his eyes through the dust and grime that clung to every part of his face, digging into his eyes. He took a breath, tried to steady the weakness in his hands, eased the glasses from side to side.

As his eyes fought to see anything through the distant line of trees, he saw a reflection.

He perked up, focused again, scanned the woods more carefully, slowly, the reflection again, another to one side. He felt the surge of his heartbeat, could see enough of the shape to know he was looking at a cannon barrel. The questions came now … so close to the edge of the woods? Why would they put a battery … now he saw more of the reflections, the low angle of the sun revealing more brass, more barrels, some standing in the wide open. But as his eyes adjusted, picking out what he was searching for, he could see the artillery pieces spread out in a long row, stretching out into the trees, hidden there, then appearing again, another clearing farther down. There was movement as well, teams of horses, more guns brought forward, put into line. Down the line beside him, other officers were standing, staring out as he was, some of them calling to him. He did not respond, but he knew what was coming, lowered the glasses, stared for a long moment, the thought tearing through his brain, the tactic that would actually work.

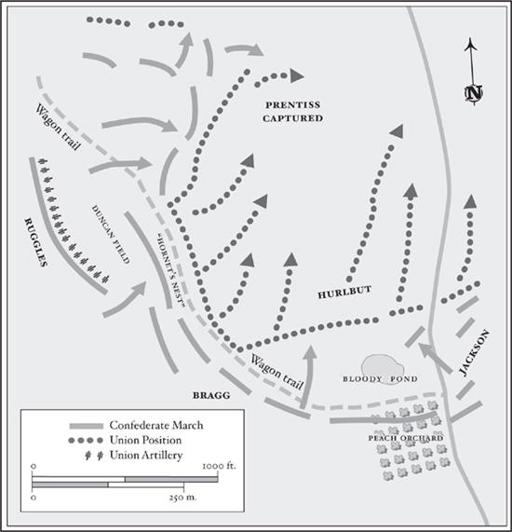

The Confederate general was Daniel Ruggles, commanding a division under Braxton Bragg. Like so many of the rebel commanders, Ruggles had become infuriated with the grotesque inefficiency of pouring men across the open ground into a position no one had been able to move. Ruggles had his own answer to what his commander had not yet solved. On the southwest edge of Duncan Field, Ruggles placed artillery pieces drawn from every battery anywhere near that part of the rebel position. As Confederate troops looked on expectantly, Ruggles placed into line a total of sixty-two cannon. When they were ready, their crews completing the task of positioning and loading the pieces, Ruggles gave the order to fire.

The shower of shells erupted mostly behind the Federal lines, the men across the front doing what they had done all afternoon, keeping low, praying desperately that their makeshift cover would offer them protection. But unlike before, the cannonade did not stop, there was no halt while lines of infantry began their march across the deadly field. This time the artillery kept up their assault, and what remained of the trees were shattered, along with the men unfortunate enough to be perched anywhere close. Prentiss had ridden back to his usual position behind the line, but that was very quickly the wrong place to be. As so often happened, the gunners were aiming too high, overestimating the distance to the Federal front lines. If the men were protected by the miscalculations of the rebel gunners, behind them the supply and ammunition wagons, the ambulances, the fields of wounded men were not. In minutes the barrage from Ruggles’s guns had obliterated most everything behind Prentiss’s lines, including nearly every artillery battery in the Federal center. At the same time, those few staff officers who dared brave the onslaught brought Prentiss the worst news imaginable. On both sides of him, rebel troops were pushing forward their advance, closing the ring around the last stronghold of Prentiss’s Division. That attack had completed the task that had begun hours before, shoving Wallace’s Division and Hurlbut’s men completely away. Prentiss attempted the only remedy open to him, calling forward reinforcements from behind, the desperate hope that someone could pour fresh troops, or reposition their forces to come to his aid. But the couriers either disappeared or returned with word that the rebel forces had cut off the last route open to him, ending any hope that reinforcements could reach Prentiss at all.

CLOUD FIELD APRIL 6, 1862, 5:26 P.M.

The cannonade across Duncan Field had grown quiet, the rebel gunners understanding that what they had not yet destroyed, Prentiss had withdrawn. But from the rear, blasts of canister were ripping through those men who were pushing that way, the one road Prentiss himself was trying to reach. With his men pouring back toward him from the sudden outburst of artillery, Prentiss halted the horse. He sat motionless for a long minute, a handful of his staff still with him, no one speaking, the staff waiting for the next order he would give them. He stared at the woods, thick smoke pouring through the trees, more of his men falling back. It was not what he had seen before, no typical retreat from an overwhelming force of the enemy. These men were retreating from behind him, were running from rebel batteries that now had closed the last gap he could use that would allow any of his men to escape. He tried to feel the energy, to rally them, to put men into position, knew there were officers doing just that, doing what they were supposed to do. But he felt something else, a kind of despair he had never experienced, had never hoped to understand. More of his men were flowing into the field, some gathering near a pair of log houses, seeking shelter. But the musket fire was reaching them now, and there was no shelter, no place for any of them to hide. He closed his eyes, wiped away what he knew was in the textbooks, that what officers were taught had no meaning to him at all. The thought in his mind now was clear and vivid. If I continue this fight, I will lose every last man. We are surrounded.

He turned, the staff looking past him, seeing all that he had seen, and gradually they looked toward him, some of them understanding what the next order would be.

“Gentlemen, we have no other options. We must not sacrifice these men who have fought so well this day. I will not see them butchered.”

He reached back to his saddlebags, could not avoid the shaking in his hands, the emotion tightening his throat. He pulled out a white shirt, a spare he always kept close, the officer’s decorum. But there was only one act of decorum now. He looked again at the men around him, at the soldiers in the wide field, pulled his sword, attached it to his shirt, began to wave it over his head.

BAUER

SOUTHWEST OF PITTSBURG LANDING, NEAR CLOUD FIELD APRIL 6, 1862, 5:00 P.M.

H

is last shot at the enemy had come at point-blank range, a blast straight into the face of a rebel who lunged at him with a bayonet. But there was no chance to reload, the lines around him collapsing completely. Bauer had no choice but to follow the others, the entire regiment pulling away, much more of an orderly retreat than they had experienced that morning. The officers had kept them in control, the sergeants holding the lines at least partially intact, some men firing a random shot back toward the advancing rebels, a meager attempt to slow their pursuers. For a while, the rebels seemed to stay with them, more scattered volleys as both sides crushed through thickets and dense brush, stumbling over fallen limbs and the remnants of shattered trees. Along the way, they slid down into gullies, falling over the bodies of their own men, those shot down before them, some of the wounded who had been pulled back to a

safe place

. In every ravine, the men forced themselves up the far sides, becoming targets for the enemy who might be close behind, taking the time to fire a volley from the ridge behind them.

There was panic in some, always, but Bauer kept his focus on the men around him, felt the strong presence of the sergeant who pushed him from behind, Champlin keeping a tight hold on the discipline and order of the men closest to him. All along the line it had seemed to work, their retreat methodical and orderly. Bauer struggled to climb yet another ridge, struggled in soft dirt, and to the front, a lieutenant, someone Bauer had never seen, ordered them about, to turn, form a line, give the pursuing rebels a volley to slow them down. He wanted to obey, but the wave of men continued past the officer, Bauer moving with them, even Champlin understanding that the time for a neat battle formation had passed. Bauer could hear the struggles of the men around him, harsh breathing, some stopping for brief rests, then moving on, and Bauer shared the exhausted determination to keep going until they could finally reach that

safe place

, every man searching frantically for that next ridgeline, the next field, where there would be solid defensive lines, batteries of Federal artillery, a place where

order

would mean more than a young officer’s desperate hopefulness. After a while, the pursuit by the rebels had seemed more distant, less dangerous, the enemy as exhausted as the men they chased, maybe more so. The bluecoated officers had rallied around that, the men on horseback who guided the lieutenants, who were now convinced that the rebels would not continue their pursuit until they re-formed, found order of their own.

The officers knew that when the enemy came again, and they would come, if the Federal troops could form that line, good high ground, protected by the brush, the enemy might repeat what they had done so often that day. They might charge blindly forward into yet another massacre. But most of the blue soldiers had seen enough of that already, and when the rebels slowed their pursuit, the men around Bauer slowed as well, more of them catching their breaths, some staying in the gullies, a desperate tumble into any creek bed that held water. Some kept to the low ground, a lesson from earlier, that in the deep ravines, rebel artillery wouldn’t find them. But others, Bauer included, had learned that those same gullies could become death traps, rebel infantry pinning men down in places where escape was impossible, enfilade fire from one end of a ravine that might sweep the low ground with deadly effect.

After a lung-crushing run up a long incline, pushed still by Sergeant Champlin, Bauer had broken out into a wide field, was surprised to see the familiar formation of a camp, rows of so many tents. Rebel artillery had found the camp as well, and clearly there had been fighting in the area, some of the tents cut apart by musket balls and canister. He stopped, Champlin not pressing now, and Bauer sat on a wooden crate, noticed a headquarters flag, a Stars and Stripes flying over a larger tent. Federal artillery was positioned there, a single battery who watched the oncoming troops with a hint of panic. The artillerymen were bringing forward their teams of mules, and Bauer could see that they were less interested in seeking targets than in preserving their own guns. In short minutes, the cannons were hitched to their limbers, their single officer leading their retreat out of the field.

Bauer saw Champlin sitting as well, others taking advantage of the obvious lull, but the officers wouldn’t allow much of that, and quickly, men on horses rode through the tent rows, ordering the men to their feet. Bauer looked back toward the low ground he had crossed, thick trees hiding anything beyond, watched as more of the retreating men climbed up into the open field. Some slowed to a staggering march, some were bandaged, walking wounded led by officers whose horses carried wounds of their own. Bauer stood, but his legs wouldn’t go, and he leaned against a naked flagpole, glanced down at the empty musket in his hand, the image of the last dead rebel still with him.

There had been too many horrors that day, no way to erase any of that, his ears still ringing from the astounding volume of musket fire thrown across such tight spaces in never-ending waves, a steady hum and roar like some ungodly swarm of hornets. On the retreat, the men who littered the ground were nearly all in blue, and it was impossible to ignore the gut-twisting sight of so many pieces of men, severed arms and legs, corpses chopped in half by cannon fire, some shredded by canister. Many faces were unrecognizable, gone altogether, but some men were still intact, their bodies twisted in grotesque shapes, untouched but for a single wound, a barely noticeable speck of blood, a small hole in a man’s head. So many had their eyes open, and Bauer could not escape that, either, the dead seeming to watch him as he moved past, the eerie notion flowing through his mind that even in death, they were seeking something, an answer, an explanation, some kind of relief he could not offer them.

As the blue troops retreated farther, there were fewer of those men, fewer pieces of bodies, fewer smears of blood on broken trees, fewer pits of smoking ground. But there were even more wounded, the men who had crawled back out of harm’s way, seeking the rear of a battleground where the

rear

had ceased to be. Many of those were out there still, no one to help them. That settled into him worst of all, the men who screamed at him as he passed, but there could be no stopping, the sergeant making that profanely clear. There were no ambulances here, no stretcher bearers. He had told himself he would go back, they would all go back, that the wounded would be found, cared for. Even if the rebels got there first, Bauer felt some hope in that, had understood finally that those men were not devils after all, that surely they would not slaughter the men they had injured. With every new assault, the enemy had become much less beastly, the death of so many of them so close in front of the peach orchard and the wagon trail taking some of that aura away. The rebels had come to them in perfect waves, what became an obscene rhythm to their attacks, one line after another driven back with amazing loss. Each time, there seemed to be a perfect pause, giving time for the men in blue to reload, to prepare. Then, when the new wave approached, it happened just as before, that the rebels would walk toward them again, so close that Bauer could see their expressions, terror and ferocity, the rebels stepping closer through what remained of the brush and timber, until the men in blue wiped them away, obliterating the lines once more.

The men were starting to move, prodded by officers, the sergeants doing their jobs again. Bauer spied a canteen near a collapsed tent, begged silently that it not be empty, picked it up, felt the heft, at least half full. He drank, ignored whatever liquid it was, felt a sharp sting from something alcoholic. Champlin was there now, others who had seen his good fortune, and he offered the canteen, said only, “Liquor.”

One man grabbed it from his hand, seemed not to care at all, and across the field, he saw others rummaging through the tents. Bauer looked again at the Stars and Stripes, hanging limp, and he looked around, thought of Hurlbut, the general he had never seen before, had barely heard the name. The flag hung above a headquarters tent as though nothing at all had happened, and he convinced himself it had to be Hurlbut’s camp. Makes sense, he thought, since it was Hurlbut who took us out of that fight. He had no idea where General Prentiss was, had heard the astounding rumor pass through the lines that Prentiss was gone, killed perhaps, most of the rest of his division captured by the rebels. He wouldn’t believe that, knew only that the 16th Wisconsin was mostly right here, familiar faces around him now, rallied by their own flag, held upright by a young man on foot, who stood now with a gathering of officers on the far edge of the field. Bauer’s brain had scrambled so many of the awful images, but the men who flowed across the field were seeing what Bauer saw, seemed to move toward the flag as though by instinct. It was the training to be sure, but more now an aching need for camaraderie, for being with their own, friends seeking friends.

Through much of the fighting, there had been orders shouted at them from behind, the lieutenants who screamed out the ridiculous commands no one needed to hear. One stuck in Bauer’s mind now,

Aim for the officers

, and he wondered why any lieutenant would hope for the death of his counterpart. Bauer had ignored that, as had most of the riflemen around him, Willis in particular calling back to the lieutenant that it wasn’t officers who were shooting at

him

.

In the pauses between assaults, Bauer had marveled at the rebels who still came, not to fight, but to drag away friends, or hoist up the wounded, giving aid to anyone who needed it. A few of the men around him, Willis included, had no such admiration, and shots took those men down as well. But Bauer would not participate in what seemed to be a different kind of slaughter, something indecent. He couldn’t avoid a surge of respect for men who cared less for themselves than for another who had fallen. Bauer had tried not to think about Willis, had no idea where he was now, what might have happened to him. He felt hesitation still, wanted to stay out in the open field, searching the faces, knew that Willis would not leave the line, that no matter Bauer calling to him, Willis had kept up his musket fire, had even ignored the captain’s order to pull back. There were always those men, the ones who wanted one more look, one more kill, but the enemy was pouring toward them in a wave that, finally, they could not hold back. Damn you, Sammie, he thought. Sometimes

retreat

is the right thing to do. You can kill more of them tomorrow, but today … we’ve done all we can. He still searched the faces, many familiar, many more not, Illinois men, Indiana, Iowa. Hurlbut’s men. Maybe we belong to him now.

Prentiss

. Always heard good things about him. Wish I’d have known him. Need to find out more about him, for sure. Hell of a thing to be led by a man you never see. Maybe he’s out there, just like Sammie, still finding a way to fight the secesh.

He fell into a loose column, moved along a narrow rutted trail, paid more attention to the sergeant than any horseman. He looked at the others around him, the ones following the flag, a hundred or more from the 16th, asked himself, how many are we now? How many ran like hell this morning? Well, you did, for one. He suddenly thought of the loudmouth, Patterson, shot down in the first minutes of the dawn. Where would he be now? He wouldn’t have lasted a single minute on the line out here. Good thing Colonel Allen was able to gather us up, send us back out there, joining up with General Hurlbut’s men. I guess it was a good thing.

Allen

. Dammit, him too. He had seen the colonel go down, a hard wound that knocked Allen from his horse, a shower of musket balls that killed yet another horse beneath him. The colonel had been treated, bandaged, had shouted down a doctor who had tried to have him hauled back behind the lines. But the wound was bad, and Allen had finally succumbed to the weakness of that, was finally taken away on a stretcher. Dead? Bauer didn’t want to think of that, either. He tried to focus on the backs of the men who walked in front of him, wished now he could have stayed back, still wanted to find Willis. Come on, Sammie. You’re already a hero. To me anyway. You’re a better soldier than I am, for certain … but there’s a time to give it up. The damn secesh were just too many, and if General Prentiss is gone, and Colonel Allen … we didn’t have a choice but to move it holus-bolus out of there.