A Blaze of Glory (17 page)

After a moment, she said, “My cook, Gloria, has been instructed to prepare a warm dinner for us, General. Your staff is most certainly invited. A day like this calls for something to warm the insides of body

and

soul. She does prepare a wonderful potato stew, which I hope your men will find appealing.”

Johnston gave her arm a slight squeeze with his own.

“You are more generous than we deserve, Mrs. Inge. My staff will be grateful, and I assure you, it will come from the heart.”

The words tumbled out awkwardly, and he stopped himself, didn’t want any hint of affection to seep into their conversation. His mind rolled over the words.

From the heart

. What’s the matter with you? She has been nothing but kind, and her graciousness comes from loyalty, nothing more. He struggled to respond, to do away with the awkwardness that seemed to infect him in every social setting.

“My wife is not especially skilled at making soup. In Texas, there are potatoes, of course.”

“I did not know that, General.”

He stopped again, more frustration. But the mention of his home touched a place he had tried to keep hidden, a crack opening in that part of him that held so many memories.

“China Grove. That’s the name of my plantation. Beautiful place. Well, it’s more of a ranch, I suppose. We do grow cotton there. Sugarcane as well. I have a truly magnificent orchard, fruit and nut trees of all types. And I grow vegetables of all sorts. I truly enjoy that, digging the soil. It is one of those quiet joys that takes a man away from everything else. My wife Eliza understands that.” He paused. “I do wish to return there very soon.” He could not help thinking of his home, knew the fruit trees were beginning to blossom, realized with a sudden sharp sadness that he would miss the opportunities for the slow strolls with Eliza, both of them admiring the fragrance of the flowers, what she spoke of with quiet reverence, the trees slowly birthing their bounty, a gift from God they should never take for granted.

“Is it near the gulf, General?”

“China Grove?” He was surprised by the question, wondered if she was simply being polite to ask. “A dozen miles perhaps. Brazoria County, near Galveston. Have you been there?” He scolded himself again, thought, of course she hasn’t been there. No one has been there but Texans. She laughed softly, her voice holding a musical gentility he had heard from so many of the people of the town.

“Oh my, no, General. We have never traveled west of the Mississippi River. The colonel prefers to stay close to home.” She paused, and he understood why. She continued, a colder tone in her voice. “Of course, in these times, he must do his duty.”

He had become more curious about her husband, knew he was widely respected in Corinth, but served in a unit Johnston knew nothing about.

“Have you received any letters from him recently?”

He immediately regretted the question, far too personal, was even more annoyed with his social clumsiness. Again, she seemed not to notice, said, “Last week. He was somewhere to the east, in Alabama. He could not say with detail.”

“No, I suppose he could not. It is not proper for an officer to reveal his whereabouts, with the enemy so close. Messages can be intercepted, and enemy cavalry does precisely what we do, patrolling the countryside, seeking such information. It is all a part of the game we must play. Probing, seeking information, keeping a close watch on each other’s movements, positions. Your husband certainly understands that.”

She said nothing, and he was grateful for that, had never been comfortable in casual conversation with anyone, certainly not the wife of one of his officers. He stared down the hill toward her home, thought of the warmth that was awaiting them, a pang of anticipation in his stomach for the meal he knew her servants would prepare. He thought of Eliza now, could never completely avoid his homesickness.

“My wife writes when she can, but she is so very busy with China Grove. So many details, so much work to do. I regret leaving her, but, of course, it can be no other way. As you understand, madam, it is difficult being absent from family. My son is in Richmond, serving on the staff of the president.”

She turned toward him.

“I am surprised by that, General. I have heard that many of our senior officers have their progeny serving close. Is it not your privilege to do the same?”

“That’s precisely why I do not, madam. My son William is a capable officer, but there are challenges enough in this command without anyone suggesting that I make a place for my own son. Actually, my staff is smaller than most. Some fault me for that, but I find it to be an advantage. Less complaining, less bickering. I have always felt a large staff is too much tail for the kite. There are those in this army who do not agree. That is, I suppose, their right. Unless it interferes in the job we must do.” He shut off the words, the voice inside of him angry. Stop this mindless jabbering! She does not care about the business of the army. “My apologies, madam. It is not necessary for you to suffer the goings-on of a soldier with too much on his mind.”

“Nonsense, General. If I may offer, though, I would suggest you find the opportunity to write your wife as often as you are able. It must be terribly difficult for her to be so far away from both her husband and her son.”

His steps slowed, her words striking him in a very cold place. She seemed to notice the change, looked at him, said, “I’m sorry, is that not appropriate?”

“William’s mother is not alive, madam. Eliza is my second wife.”

She pulled her arm away, put her white gloves to her face, genuinely upset.

“Oh dear me. I am so very sorry. Please forgive my indiscretion. I should not be delving into such personal matters.”

He glanced back behind him, saw his staff stopping, held by the firm hand of Governor Harris, keeping their distance, reacting to the halt in his steps. Johnston nodded slightly to Isham, knew the governor would be watching him carefully, sensitive to protocol, quick to respond to anything Johnston might suddenly need. He was suddenly grateful for that, the man’s friendship, something of

home

in that, a good friend, not merely a subordinate who follows orders. He looked again at Mrs. Inge, saw the deep concern lingering in her eyes.

“Please do not be concerned, madam. That tragedy was a very long time ago. And it is not a matter for avoiding. I have come to accept it as the Way.”

He looked down briefly, knew that Isham would know that to be a lie.

A sharp breeze swirled suddenly around them, leaves in the air, a harsh whisper through the bare tree limbs above them. He saw her shiver, her face very red, and she closed her eyes for a brief moment, fighting the cold. He extended his arm again, which she seemed grateful to take. She gripped him more tightly, but he knew his coat could not warm both of them, was barely enough to warm him. He looked down, measured his steps, not wanting to rush her. But the chill was growing painful now, a miserable stinging in his ears, and he looked down the street toward her home, very close now. Rose Cottage had been two long blocks from the church, and he glanced at the other homes nearby, some, like hers, framed by the gray skeletons of oak and pecan trees. Some of those homes were even more grand than the Inge house, and he knew that nearly all of them were occupied by his other senior commanders. It was a show of graciousness from the citizens of a town who seemed to understand with perfect certainty that, no matter the optimistic words of their ministers, no matter the heavy crowds that filled the churches on this cold Sunday morning, it was their army that might be their only salvation.

He continued the slow pace down the hill, the wind louder now, details creeping into his mind, the papers he had been shown, reports, intelligence, all those things he would now attend to. As they reached the front walkway to her home, he could not help staring down at the blowing dust, the mud finally hardening along the roadway.

JOHNSTON

Soldiers of the Army of the Mississippi: I have put you in motion to offer battle to the invaders of your country. With the resolution and discipline and valor becoming men fighting, as you are, for all worth living or dying for, you can but march to a decisive victory over the agrarian mercenaries sent to subjugate you and despoil you of your liberties, your property, and your honor. Remember the precious stake involved; remember the dependence of your mothers, your wives, your sisters and your children, on the result; remember the fair, broad, abounding land, and the happy homes that would be desolated by your defeat.

The eyes and hopes of eight millions of people rest upon you; you are expected to show yourselves worthy of your lineage, worthy of the women of the South, whose noble devotion in this war has never been exceeded in any time. With such incentives to brave deeds, and with the trust that God is with us, your generals will lead you confidently to the combat—assured of success.

T

he order was read to every regiment by every low-level commander, passed down to each by the four corps commanders who would lead the march. Johnston had written most of the words himself, but it was Colonel Jordan, Beauregard, even Bishop Polk, who helped craft the words. It was natural for him to ask. He knew he was not good with speeches, and if this army was to perform in the field, the men must be given some spark of inspiration from the man who claimed to lead them.

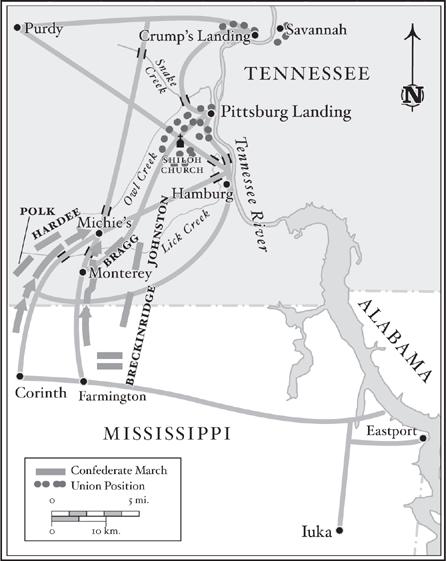

They were to march out of their earthworks at six in the morning on April 3, a quick and orderly surge of power that would flow northward on the network of roadways that spread out in parallel courses through the rolling countryside. The orders had been plain and direct, each one of the four corps commanders knowing precisely where Johnston was to be, when his troops were to march, and which route they would take. The orders spelled out the timetables, the rendezvous points, the eventual position of the battle lines and the precise moment when the attack on Grant’s army would begin. The original plan of attack called for the three corps under Hardee, Polk, and Bragg to make their rendezvous within a few miles of the Federal position, with Breckinridge and the reserves close behind. There the troops would be spread into an enormous arc, the corps side by side, to burst forward as one great mass into Grant’s encamped troops, striking hard into whatever configuration Grant’s divisions had arranged themselves in. With efficient coordination between the three primary corps and Breckinridge’s reserves, the attack would commence precisely at dawn on Saturday, April 5. The arrangement of Grant’s camps meant very little to Johnston. Every scouting report continued to insist that Grant’s army was completely immobile, and was in no way organized to receive any kind of assault. Johnston felt confident that as long as the Federal forces continued to be utterly oblivious of Johnston’s advance, there would be little that Grant could do to stop the enormous wave that was rolling toward him.

The plan had been tooled and refigured for several days, and Colonel Jordan had been tireless in traveling from headquarters to headquarters, delivering the communications directly to each of the commanders, placing maps in their hands, giving carefully worded instructions as to the logistics of the plan. With so much of the maneuver and the planning spelled out in such detail by Beauregard and Jordan, Johnston had to believe that

finally

the right people had been put in the right places. Unlike Donelson, this time capable men were in command, and with Jordan’s amazing efficiency, Johnston began to feel a sense of destiny, as though this victory were preordained. To begin the campaign, to put the troops into the roadways and direct them northward to accomplish the great victory he could already see in his mind, the overwhelming destruction of the Federal army, Johnston’s only immediate task would be to give the order that began the march.

On April 2, he did.

CONFEDERATE ADVANCE OUT OF CORINTH

ROSE COTTAGE, CORINTH, MISSISSIPPI

APRIL 3, 1862

“No, sir. They are not at the intersection. General Hardee’s troops were somewhat … ah … tardy in their movements. That delay forced General Polk to halt his men until the roads to his front were clear.”

“Well, Colonel, are they

clear

?”

Jordan looked down, and Johnston could see the same frustration he was feeling himself.

“No, sir. General Polk’s wagon trains are still close to the town.”

Johnston felt the burn in his brain, paced the room with surging anger, something he rarely did.

“Why was Hardee delayed?”

Jordan glanced at Beauregard, who sat in his usual perch on the couch. Beauregard said nothing, stared at the floor with grim resignation. Johnston ignored him, was beginning to understand that, with Beauregard’s illness, it was Jordan who was filling the void and was probably responsible for many of their decisions. Jordan responded in a quiet, measured voice.

“General Hardee insisted that his order to march be put into writing. The original order had been given him this morning, but he would not accept it … verbally.”

“So? Did you comply with his wishes? Did you write out the order?”

Jordan took a deep breath, his careful responses digging into Johnston’s fury.

“Yes, sir. But … in the confusion of all the activity at headquarters … the order was not delivered until this afternoon.”

Beauregard spoke now, his voice still raspy, the struggle to speak through the nagging illness.

“The roads are not as we had hoped. General Bragg is not pleased that his route of march is very difficult. He has been unable to reach the first rendezvous point. There is still too much mud. The horses cannot pull the wagons with any hope of speed. Artillery is mired. General Bragg’s report was somewhat … profane.”

Johnston absorbed the news as he had absorbed it all day. Besides the brain-piercing frustration was a heightening sense of alarm.

“If we do not assemble our forces at the desired point, we will be unable to effect the attack. We will be forced to delay. Every moment we delay is a moment the enemy could determine our strategy.”

Beauregard nodded, as though this had been expected all along. Beauregard rubbed a hand on his throat, made a low cough.

“I have always believed that an uncertain offensive was unwise. Perhaps we should have waited for the enemy to emerge from his camps, and make his strategies known to us. We could have struck him on the march, when he was strung out, in no position to make a defense. The mud would have been

his

enemy and not our own.”

Johnston stared at the ailing man, moved to his usual chair, sat slowly, never took his eyes from Beauregard.

“This plan of attack … was

yours

. Now you are telling me this is not the correct plan? You wait until our army is in motion …”

The words choked away, and Johnston forced himself to keep the anger tightly inside, was never a man to launch violent words at anyone. Beauregard seemed not to notice Johnston’s mood, said, “I merely point out that it is always good strategy to strike an enemy while he is unprepared.”

“Do you have some evidence that General Grant is

prepared

now?”

Beauregard seemed to run out of energy, and Jordan read his commander, spoke up.

“No, sir. Not at all. But there is risk, as you say, that if we delay, the enemy will become aware of our intentions. If we allow him the time, he could prepare a firm defensive posture.”

Johnston was beginning to despise Jordan, a silky smoothness to the man’s speech.

“I understand risk, Colonel. I have lived with risk my entire career. Without risk there is no hope of achieving anything positive. Is that concept alien to you? The enemy is perched in his camps with orders, apparently, to sit idle until he is reinforced. I know of no situation that could benefit us more, that could lessen our

risk

any more than the opportunity General Grant has presented us.

Opportunity

, Colonel. Consider the word, if you please. We must seek the means to drive an entire army from our soil. From all we can gather, that means lies before us with perfect clarity. The weather has improved and yet I hear excuses that miserable roads are grinding our advance to a standstill. I did not expect any such complaint. Neither did you.” Johnston calmed himself as much as possible, a desperate effort to hold to some kind of decorum.

“If I am not mistaken, you labored over these plans for weeks, even before I reached Corinth. You both have shown nothing but confidence that this would be successful. Now … you tell me that we should rely instead on the fantastic notion that General Grant is so magnificently stupid, he would spread his army all over the countryside, even more so than he already has. He would march his people in such a way as to invite attack when he is most vulnerable. He knows we are observing him, does he not? Our cavalry is not invisible. He has picket lines and guard posts and none of those people are blind.” He fought to keep his voice low, heard boots in the outer rooms, conversations, did not want any of those men to hear the discussion that was burrowing a deep hole into his sanity. He moved to the curtained window, drew back the soft cloth, saw a hitching post lined with horses lathered with sweat, dripping with mud. He had seen the same all day.

“Someone has arrived. There will be more reports, Colonel. See to them. Keep me informed of our movements.”

Jordan nodded, backed away, said nothing more. He pulled open the door behind his back, and Johnston said, “Leave the door ajar. This council has concluded.” He looked at Beauregard now. “Unless you have something to add.”

Beauregard shook his head weakly.

“I have nothing to add. It is in God’s hands now.”

Johnston tried to avoid the thought, but it flooded through his mind.

God did not design this attack

. He kept his silence, moved out into the larger room of the elegant home. He had always enjoyed Mrs. Inge’s décor, the portraits of her relatives, glassware crowding the mantel, set there as a precaution, out of the way, the careful hostess aware that her sitting room and sunporches had been converted into a place for soldiers. But still there were touches of family, of civilians, small paintings, tapestries, soft lace on colorful chairs. But he would see none of that now, felt suddenly as though the house were a maddening prison, smelling of mud and sweat and dirty wool. In several of the rooms, staff officers and aides had left a trail, the unavoidable dirt of the roadways smeared onto wooden floors. Johnston heard the chorus of voices throughout the headquarters, the chatter of their reports unable to disguise anger and frustration. They noticed him now, men suddenly standing back, some at attention, acknowledging him, and he stared at them, scanned the papers in their hands, could see his own anger on their faces.

He said nothing, heard movement behind him, from the smaller office, caught the ugly smell of medicine, a sickly odor as Beauregard slid out past him. The Creole moved with slow purpose, made every effort to keep himself steady, a good show for the staffs. Johnston said nothing to him, watched the man move outside, his own aides gathering around their commander. He will return to his quarters, Johnston thought. Best place for him to be. Johnston had a sudden burst of cold concern, had not really considered: What if he does not survive this? How ill is he, after all? No one seems to know, and he never seems to get better. What will we lose if he passes on? Johnston looked at the others, some moving again, papers, low conversation. His question had no answer, his mind too filled with the chaos of his army.