A Billion Wicked Thoughts: What the World's Largest Experiment Reveals about Human Desire (12 page)

Authors: Ogi Ogas,Sai Gaddam

BOOK: A Billion Wicked Thoughts: What the World's Largest Experiment Reveals about Human Desire

9.29Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

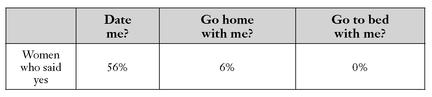

Men were apparently more motivated to sleep with a woman than to date her. But what about women? What percentage of college women do you think would say yes to an invitation to go home with an attractive college guy who just walked up to her on campus?

For almost a decade, Hatfield and Clark couldn’t get these dramatic results published. Some journal editors suggested that it must be something unique to Florida State—perhaps the torrid weather. Journal editors expressed disbelief, denigrating the research as unscientific, naive, or simply too provocative. One editor wrote, “This paper should be rejected without possibility of being submitted to any scholarly journal. If

Cosmopolitan

won’t print it then

Penthouse Forum

might like it.”

Cosmopolitan

won’t print it then

Penthouse Forum

might like it.”

But by now, Hatfield was used to such setbacks. She and Clark repeated the same study at Florida State. They obtained nearidentical results: this time, no women agreed to go home with the male research confederate. The results were finally published in the

Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality

in 1989. Today, the paper is considered a social psychology classic.

Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality

in 1989. Today, the paper is considered a social psychology classic.

In the 2000s, the Hatfield and Clark study was replicated in Belgium, Denmark, and Germany with similar results. The results were also reinforced by the responses of more than 6 million users on the online dating site OkCupid. One primary feature of OkCupid is member answers to member-created questions. One such question asked, “How would you react if someone sent you a text message and quickly started talking about sex?” There was an enormous gender difference in the responses: only 15 percent of women said they would react positively, compared to 60 percent of men. Another question asked, “Would you consider sleeping with someone on a first date?” Most women said no. Most men said yes.

These fascinating results suggest that the desires of men and women are

different

. But what is the source of this difference? Maybe it’s culture. Perhaps men and women possess fundamentally similar desire software, it’s just that Western society encourages us to express our desires differently. How much would you be willing to bet that the brain software for female desire is the same as the brain software for male desire?

different

. But what is the source of this difference? Maybe it’s culture. Perhaps men and women possess fundamentally similar desire software, it’s just that Western society encourages us to express our desires differently. How much would you be willing to bet that the brain software for female desire is the same as the brain software for male desire?

The pharmaceutical companies bet millions.

A SEXIST DRUGAngina pectoris is a medical condition that causes severe chest pain due to the obstruction of the heart’s blood vessels. Drugmakers are interested in this condition because of its prevalence: roughly 6.5 million Americans experience angina, mostly in middle age. In 1996, researchers at Pfizer’s Kent facility in England developed a test compound known as 5 cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor. The Kent researchers were one of many teams at Big Pharma companies battling to reach the holy grail of drug discovery: a successful Phase III treatment of human subjects. Success would mean hundreds of millions of dollars of annual drug profits. Unfortunately for Pfizer, Phase III was a failure.

The phosphodiesterase inhibitor had no significant effect on unblocking the heart’s blood vessels. But the researchers did notice something quite interesting. Even though the male subjects’ angina did not improve, many of them asked for more of the test drug. When the researchers asked why, the men rather shyly explained it was helping their marriage. The researchers took a closer look at the drug’s effects. What they found would revolutionize male desire. The drug did facilitate blood flow after all—just not where they expected. They published their findings in an impotence research journal as “Sildenafil: An Orally Active Type 5 Cyclic GMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase Inhibitor for the Treatment of Penile Erectile Dysfunction.”

Viagra was born.

When Pfizer launched Viagra in 1998, its share price doubled within days. Since then, the little blue pill has been a multibilliondollar cash cow and transformed the sexual lives of millions of middle-age men. But what was good for the gander was surely good for the goose. Almost immediately, Pfizer and other Big Pharma multinationals turned their attention to developing “pink Viagra”—a pill to treat female sexual dysfunction. Around the world, state-of-the-art biotech labs became focused on developing an effective female aphrodisiac—what in previous eras had been an urban myth known as the “Spanish fly.” The prize for this research? With twice as many women as men suffering from “sexual desire disorders,” the profits from pink Viagra could be astronomical.

Vivus, a California-based biopharmaceutical company that designed drugs to restore male sexual function, joined the quest. It started testing a Viagra-like drug that widened blood vessels and increased blood flow, known as a

vasodilator

. It reasoned that increasing blood flow to the vagina would increase women’s feeling of arousal, just as it does for men. It even hired a documentarian to shoot pornographic movies to test female subjects’ arousal. But after dozens of trials and $10 million of costs, the Vivus vaso-dilator failed to boost female desire.

vasodilator

. It reasoned that increasing blood flow to the vagina would increase women’s feeling of arousal, just as it does for men. It even hired a documentarian to shoot pornographic movies to test female subjects’ arousal. But after dozens of trials and $10 million of costs, the Vivus vaso-dilator failed to boost female desire.

Pfizer itself encountered similar problems. It tested Viagra itself on more than seven hundred women, including two hundred estrogen-deficient women. None of the women felt more aroused, though many reported headaches. Next, Pfizer tried Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) a compound that is believed to control vaginal blood flow. This also failed to show any improvement in female libido. In fact, almost every attempt at stimulating female desire through “peripherally acting agents” was a failure. Though the male brain responds to the physical changes wrought by Viagra, Cela, and Levitin with increased sexual interest, the female brain does not.

It wasn’t just the

behaviors

of men and women that seemed different—their

brains

seemed different, too. Why did so many Big Pharma and biotech companies fail to find female Viagra? The answer also explains Hatfield and Clark’s dramatic results.

THE MIND-BODY PROBLEMbehaviors

of men and women that seemed different—their

brains

seemed different, too. Why did so many Big Pharma and biotech companies fail to find female Viagra? The answer also explains Hatfield and Clark’s dramatic results.

Meredith Chivers is an assistant professor of psychology at Queen’s University in Canada. As the director of the Sexuality and Gender Laboratory at the university, she is one of the world’s leading researchers on the neuropsychology of female desire. In 2004, Chivers conducted an ingenious experiment to find out what turns women on.

She invited women to her lab and showed them a variety of erotic pictures. Chivers measured their arousal from viewing the pictures in two different ways. First, she asked them how they felt—a measure of conscious,

psychological

arousal. Second, she inserted a plethysmograph into their vaginas—the female version of the device used to measure erections in the jar of pennies experiment. The plethysmograph measured blood flow in women’s vaginal walls—a measure of

physical

arousal. But the most interesting part of Chivers’s experiment was the pictures themselves.

psychological

arousal. Second, she inserted a plethysmograph into their vaginas—the female version of the device used to measure erections in the jar of pennies experiment. The plethysmograph measured blood flow in women’s vaginal walls—a measure of

physical

arousal. But the most interesting part of Chivers’s experiment was the pictures themselves.

They consisted of photographs depicting exercising men, exercising women, gay sex, lesbian sex, straight sex—and monkey sex. One of the images showed copulating bonobos, a type of primate also known as the pygmy chimpanzee.

So which images elicited

physical

arousal in the women?

All

the images, even the monkey porn. Women’s vaginal blood flow increased after viewing each erotic picture. Which images elicited

psychological

arousal—which caused the women to

say

they were turned on? Heterosexual sex generated the greatest psychological arousal, followed by lesbian sex. Watching people exercise wasn’t much of a turn-on. The reported amount of psychological arousal from watching monkey porn? A very emphatic zero.

physical

arousal in the women?

All

the images, even the monkey porn. Women’s vaginal blood flow increased after viewing each erotic picture. Which images elicited

psychological

arousal—which caused the women to

say

they were turned on? Heterosexual sex generated the greatest psychological arousal, followed by lesbian sex. Watching people exercise wasn’t much of a turn-on. The reported amount of psychological arousal from watching monkey porn? A very emphatic zero.

In other words, there was a dissociation between the conscious arousal of the mind and the unconscious (or semiconscious) arousal of the body. When the exact same experiment was conducted with male subjects, there was virtually no dissociation between the two types of arousal. If a man was

physically

turned on, he was also

psychologically

turned on. And none of the men got turned on by monkey sex.

physically

turned on, he was also

psychologically

turned on. And none of the men got turned on by monkey sex.

This intriguing dissociation between the mind and body in women seems to reflect a common experience among women that is frequently unvoiced. “Thanks to you women who wrote about the dichotomy between getting turned on and (intellectually) being turned off,” writes one woman on

Salon.com

, in response to an article addressing why women don’t watch porn. “Just last night my husband was asking me to watch porn with him and I was trying to explain that after about 10 minutes of it I’m more turned off than on (even if I’m turned on too—the other part won’t let me enjoy it). I think it would be easier to be a guy when it comes to porn—having all this conflicting stuff flying around my brain and body makes me crazy.”

Salon.com

, in response to an article addressing why women don’t watch porn. “Just last night my husband was asking me to watch porn with him and I was trying to explain that after about 10 minutes of it I’m more turned off than on (even if I’m turned on too—the other part won’t let me enjoy it). I think it would be easier to be a guy when it comes to porn—having all this conflicting stuff flying around my brain and body makes me crazy.”

In the same online discussion, when several men expressed disbelief that it’s possible to be physically aroused and psychologically grossed out, another woman responded: “It’s hard not to notice when your panties are soaking wet. It’s just that being aroused by something that

disgusts

you is very, very unpleasant.”

disgusts

you is very, very unpleasant.”

After obtaining her provocative results, Chivers reviewed 132 different laboratory studies published between 1969 and 2007 that simultaneously investigated physical and psychological arousal. The results were very clear. Men experienced a strong correlation between the arousal of mind and body. Women did not. In fact, the correlation between physical and psychological arousal in women was so low that it’s safe to say a woman’s vaginal lubrication is a poor predictor of what she is actually feeling. In fact, many women report lubrication and even orgasm during unwanted and coercive sex: a woman’s body responds, even as her mind rebels. In contrast, if a man is erect, you can make a very reasonable guess about what’s going on in his mind.

The conclusions from Meredith Chivers’s groundbreaking research are inescapable: psychological and physical arousal are usually linked in men, but in women there’s a disconnect. It’s as if the carnal signals from a woman’s body somehow get cut off before they enter her conscious awareness. Male sexuality, in contrast, is like the knee-jerk reflex: a message of arousal from the body triggers instant mental desire. Elmer Fudd readies, aims, fires at the slightest hint of a wabbit.

This is a profound difference in the brain software of men and women. It explains why the pharmaceutical industry’s quest for female Viagra kept running into dead ends. Stimulating the vagina or the spine does not automatically fire up desire in the conscious mind. Instead, women need to feel

psychologically

aroused. This dichotomy was even present in a rare sex survey in the 1920s that found that the most frequent complaint among a thousand married women was a failure to reach orgasm—and that their obstacles to sexual pleasure were primarily psychological rather than biological. The drug companies might have garnered better results if they had first considered the wild popularity of romance novels, which stimulate women’s minds without ever touching their bodies.

psychologically

aroused. This dichotomy was even present in a rare sex survey in the 1920s that found that the most frequent complaint among a thousand married women was a failure to reach orgasm—and that their obstacles to sexual pleasure were primarily psychological rather than biological. The drug companies might have garnered better results if they had first considered the wild popularity of romance novels, which stimulate women’s minds without ever touching their bodies.

In the past few years, Big Pharma have changed their tactics. Now they realize that any pharmaceutical solution to desire disorders will have to act on the brain itself, and likely involve conscious mechanisms. Ironically, the drug with the greatest promise for improving libido resulted from a botched attempt at solving a different problem, just like the discovery of Viagra. The German drugmaker Boehringer Ingelheim was trying to develop a fast-acting antidepressant. Though the drug, known as Flibanserin, failed in its Phase III trials, researchers found that it resulted in a surging libido for the female subjects. What part of the brain does Flibanserin target? Regions involved in the

conscious

processing of emotion. It operates by stimulating the conscious mind, not the body.

conscious

processing of emotion. It operates by stimulating the conscious mind, not the body.

In men, the sexual body and the sexual mind are united. So why are they separated in women?

THE MISS MARPLE DETECTIVE AGENCYWhen it comes to the design of our sexual brain, women appear to possess the same basic components as men: circuits to handle physical arousal, circuits to handle psychological arousal, circuits to reward sexual thoughts and behavior, circuits to control motivation, and circuits to respond to sexual cues. However, there are dramatic differences in how these components operate in the minds of men and women.

“Booty is so strong there are dudes willing to blow themselves up for the highly unlikely possibility of booty in another dimension,” observes comedian Joe Rogan. “There are no chicks alive willing to blow themselves up for a penis.” Women masturbate less, fantasize about sex less frequently, and initiate sex less often than men. Women report low sexual desire much more often than men. In fact, among medical professionals who treat sexual disorders, low female desire is the single most common complaint. In women, desire is much less likely to initiate orgasm-seeking behavior. Women are much more likely than men to pursue sex for reasons other than sexual pleasure. Women are more likely to report low desire as resulting from relationship difficulties and high desire as resulting from relationship harmony. According to Marta Meana, such findings “have contributed to the development of a theory of women’s desire as being substantially different from that of men.”

Other books

Deeper Than Red (Red Returning Trilogy) by Sue Duffy

Disarming by Alexia Purdy

Ozark Trilogy 3: And Then There'll Be Fireworks by Suzette Haden Elgin

The Epigenetics Revolution by Nessa Carey

A Few More Nights (Slice of Life) by Gaines, Olivia

Chameleon (Supernaturals) by Oram, Kelly

The Dawn Stag: Book Two of the Dalriada Trilogy by Watson, Jules

Bad Taste in Boys by Carrie Harris

Long Shot by Paul Monette

Mutation: Parables From The Apocalypse - Dystopian Fiction by Norman Christof