69 Barrow Street (18 page)

Authors: Lawrence Block

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrillers, #Suspense, #Espionage

The Village endures.

A

H YES.

Barrow Street.

I was born in Buffalo, at the other end of the state, and my first visit to New York City came ten and a half years later, in December of 1948. My father and I rode the Empire State Limited to Grand Central and stayed for three or four nights at the Hotel Commodore, right next door to the train station. We found time to visit an aunt and uncle of his, but most of the weekend was devoted to showing me New York, and we didn’t miss much. We rode the Third Avenue el down to the Bowery, where I saw a man emerge from a saloon, scream at the top of his lungs, then turn around and go back in again. We rode the ferry to Bedloes Island—since renamed Liberty Island—and saw the statue. We went to the top of the Empire State Building. We saw a Broadway show—

Where’s Charley?

with Ray Bolger—and the live telecast of

Toast of the Town,

which was what Ed Sullivan’s show was called back in the day. (At the time, I’d not yet seen a TV set; I found the monitor more fascinating than what was occurring onstage.)

I must have known then that I’d wind up in New York.

There was another visit a couple of years later, with my mother and sister along this time, and all four of us stayed at the Commodore. We Saw

South Pacific

this time. I don’t remember where else we went, or what else we did, but one place I’m sure we didn’t get was Greenwich Village. I never got to the Village until the summer of 1956, when I lived there.

I went to Antioch College, in Yellow Springs, Ohio. There were a lot of things that set the school apart, but its defining element was a program of cooperative education. Students spent half the year on campus, the other half out in the world, acquiring vocational and life experience in an appropriate short–term job. Like many of my classmates, I spent my whole freshman year in Yellow Springs, and in August of 1956 I went off to New York to begin my first co–op job, as a mail boy at Pines Publications. I got there as I’d done the first time, on the Empire State Limited, and met Paul Grillo right there in the terminal, in front of the big clock. He’d been my hall advisor during the academic year, and now we’d be rooming together. He’d already found us a place, and told me how to get there—147 West Fourteenth Street, and I was to take the shuttle to Times Square and the IRT downtown to Fourteenth Street.

That first night, I went out exploring, and I managed to find my way to a jazz club that had come well recommended by my roommate, Steve Schwerner. It was the Café Bohemia, at 15 Barrow Street, and I stood at the bar and had a drink and listened to Al Cohn and Zoot Sims.

I explored some more over the weekend. A fellow I’d met a summer earlier when we’d both worked at Camp Lakeland lived on Bleecker Street, and introduced me to Caricatures, a coffee house on Macdougal with a batch of caricatures in the window, alone with a signed note from Maxwell Bodenheim, the archetypical Village bohemian who’d been murdered a few years earlier. The place was owned and run by a woman named Liz, who was more interested in her ongoing bridge game in the back room than in the customers out front. But she did serve cheeseburgers on toasted rye bread, and they were outstanding.

Monday morning I reported to work at Pines Publications. And by the beginning of September Paul Grillo and I, along with Fred Anliot, had moved south to 108 West Twelfth Street, and south and west to 54 Barrow Street.

Where I spent the months of September and October, until it was time to return to Yellow Springs.

That was a wonderful apartment, parlor floor front, the living room fronting on Barrow Street, a bedroom at the rear, a kitchen–dining room in between. I wrote a story there called “You Can’t Lose,” and it eventually became my first sale when

Manhunt

bought it a year later. I got friendly with the folk music enthusiasts who spent Sunday afternoons around the circle in Washington Square, and when the cops cleared the area at six o’clock, the party would move on to our place on Barrow Street.

When October ended and it was time to return to Yellow Springs, we passed the apartment to a couple of other Antiochians, and they kept it for the next three months. It may have stayed in Antioch hands for another semester, or maybe not, but eventually it went back to the landlord. Now I suppose it’s a co–op, or a condo; if it’s still a rental, it probably runs to $2500 a month. We paid $90, split three ways. Then again, I was earning $40 a week at Pines Publications, and taking home $34. All things in proportion.

It was two summers later, in August of 1958, that Sheldon Lord wrote his first novel. The book was called

Carla,

and was both set and written in Buffalo. I’d dropped out of Antioch after my second year, when I’d lucked into a job as an editor at a literary agency. I kept that job for the better part of a year, then went home to Buffalo and wrote a novel (

Strange Are the Ways of Love,

by Lesley Evans), and got an assignment from my former employer to write an erotic novel for a new publisher, Midwood Tower Books, the creation of one Harry Shorten. I wrote the book, Harry loved it, and Sheldon Lord was in business.

Sheldon Lord’s second book was

A Strange Kind of Love,

and it seems to me

69 Barrow Street

was third, but I may be wrong about that. I was back in Yellow Springs when I wrote

A Strange Kind of Love,

and I wrote

Born to Be Bad

there as well, and it seems to me

69 Barrow Street

came between the two.

But who cares?

I liked the idea of a book set in a single building, and telling the stories of its various inhabitants. And I wanted to use the Village in a book, and what better street than Barrow Street? Harold Robbins, who’d written a terrific realistic novel in

A Stone for Danny Fisher,

had followed it with some less terrific but soundly commercial books, and one of them was indeed set in a single building, and the title was

79 Park Avenue.

Why not improve in that a wee bit by reducing the number by ten? Call the book

69 Barrow Street

—an address which doesn’t actually exist, incidentally, so don’t go looking for it—and I’d give the book a clearly sexual tag while doing absolutely nothing censorable,

Hey, it’s an address, it’s a fucking number, and what the matter with that?

It was such a brilliant idea that I wondered how come Harold Robbins hadn’t thought of it first. And, years later, I found out that he had. It had been his original intention to call his book

69 Park Avenue,

and that was the title he’d attached to the manuscript when he sent it to his publisher.

But cooler heads prevailed.

As they sometimes do. Fortunately there were no cooler heads in Harry Shorten’s offices, and my title stayed.

Ages and ages ago, that was. I don’t know that I expected to be around so many years later, but I’ll tell you this: I never thought for a moment that Sheldon Lord would still be with us, or that anyone on earth would actually be reading

69 Barrow Street

in a year starting with a 2. I’m damn glad that I’m still around, and, yes, glad to say the same for Sheldon Lord, and this creation of his.

Hope you enjoyed it.

Lawrence Block (b. 1938) is the recipient of a Grand Master Award from the Mystery Writers of America and an internationally renowned bestselling author. His prolific career spans over one hundred books, including four bestselling series as well as dozens of short stories, articles, and books on writing. He has won four Edgar and Shamus Awards, two Falcon Awards from the Maltese Falcon Society of Japan, the Nero and Philip Marlowe Awards, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Private Eye Writers of America, and the Cartier Diamond Dagger from the Crime Writers Association of the United Kingdom. In France, he has been awarded the title Grand Maitre du Roman Noir and has twice received the Societe 813 trophy.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Block attended Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Leaving school before graduation, he moved to New York City, a locale that features prominently in most of his works. His earliest published writing appeared in the 1950s, frequently under pseudonyms, and many of these novels are now considered classics of the pulp fiction genre. During his early writing years, Block also worked in the mailroom of a publishing house and reviewed the submission slush pile for a literary agency. He has cited the latter experience as a valuable lesson for a beginning writer.

Block’s first short story, “You Can’t Lose,” was published in 1957 in

Manhunt

, the first of dozens of short stories and articles that he would publish over the years in publications including

American Heritage

,

Redbook

,

Playboy

,

Cosmopolitan

,

GQ

, and the

New York Times

. His short fiction has been featured and reprinted in over eleven collections including

Enough Rope

(2002), which is comprised of eighty-four of his short stories.

In 1966, Block introduced the insomniac protagonist Evan Tanner in the novel

The Thief Who Couldn’t Sleep

. Block’s diverse heroes also include the urbane and witty bookseller—and thief-on-the-side—Bernie Rhodenbarr; the gritty recovering alcoholic and private investigator Matthew Scudder; and Chip Harrison, the comical assistant to a private investigator with a Nero Wolfe fixation who appears in

No Score

,

Chip Harrison Scores Again

,

Make Out with Murder

, and

The Topless Tulip Caper

. Block has also written several short stories and novels featuring Keller, a professional hit man. Block’s work is praised for his richly imagined and varied characters and frequent use of humor.

A father of three daughters, Block lives in New York City with his second wife, Lynne. When he isn’t touring or attending mystery conventions, he and Lynne are frequent travelers, as members of the Travelers’ Century Club for nearly a decade now, and have visited about 150 countries.

A four-year-old Block in 1942.

Block during the summer of 1944, with his baby sister, Betsy.

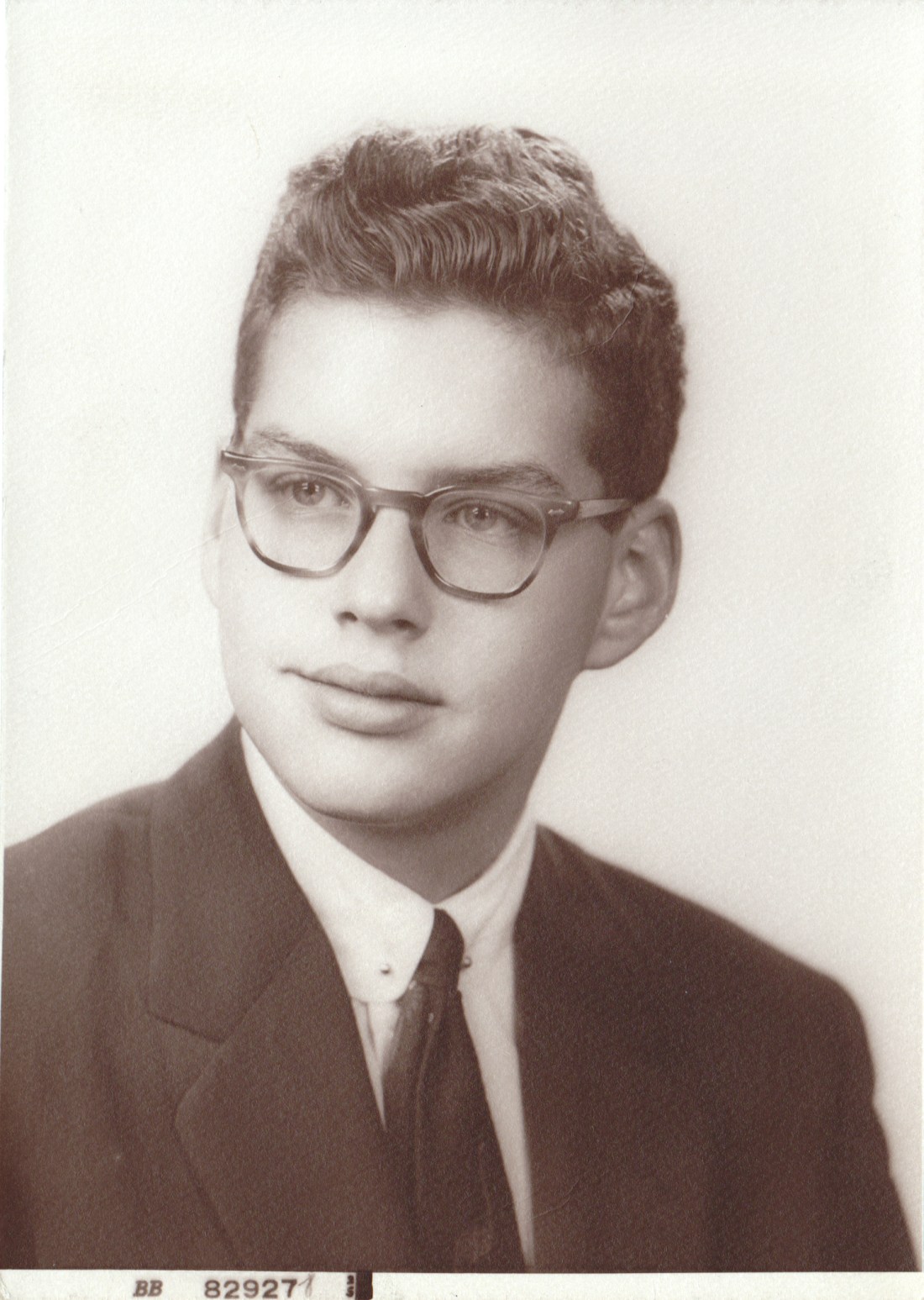

Block’s 1955 yearbook picture from Bennett High School in Buffalo, New York.

Block in 1983, in a cap and leather jacket. Block says that he “later lost the cap, and some son of a bitch stole the jacket. Don’t even ask about the hair.”