56: Joe DiMaggio and the Last Magic Number in Sports (37 page)

Read 56: Joe DiMaggio and the Last Magic Number in Sports Online

Authors: Kostya Kennedy

The next night yielded Rose a challenge far different from the one he’d just faced in the veteran and future Hall of Famer Niekro, against whom Rose had batted scores of times. Atlanta sent out Larry McWilliams, a tall rookie lefthander with an irregular, almost spasmodic motion. McWilliams had a record of 2–0 and before the game, Rose watched him closely as he warmed up, determining that McWilliams had three pitches—fastball, curveball, forkball. Rose was ready to go to work.

“I was more nervous in that game that I ever had been or ever would be pitching in the major leagues,” McWilliams remembers. “That was just the fourth start of my career and ever since I’d seen Pete get that ball through against Niekro the night before I knew that I’d be pitching against him with the streak intact. The atmosphere at the park was just amazing, electric, the crowd was so alive. This was the kind of game, you know, that if I hadn’t been on the team, I would have wanted to buy a ticket to see it.

“I really did not want to walk Pete—the people hadn’t come out to see that,” McWilliams continues. “But his first time up he ran the count to 3 and 2. I threw a fastball and he hit a rocket just foul by the bullpen down the rightfield line. I mean he hit that ball really hard. So then I got shy and threw a curveball and walked him. I was a little disgusted by that. The next time Pete came up I wanted to get ahead of him in the count so I threw a fastball on the first pitch and he hit a line shot right back at me that I just reached behind and was able to catch. It was a reaction-type play; I didn’t think about it before I caught it. That ball was a base hit most nights. And if I remember right Pete applauded the catch, literally clapped a few times and nodded his head, before he went back to the dugout.

“I faced Pete once more and he hit a pretty routine ground ball to shortstop. Jerry Royster was playing there and he threw him out. We had a big lead by then and after the fifth inning the manager, Bobby Cox, took me out of the game and told me to go shower up.”

Rose’s fourth at bat came in the seventh inning against the sidearming righthander Gene Garber and for the third time Rose hit the baseball on the nose, lining it chest high and into the glove of third baseman Bob Horner. The ball got there so fast that Horner threw across the diamond and doubled off the runner, Dave Collins, at first base.

By the time Rose came to the plate in the ninth inning, with two outs and nobody on, Atlanta led 16–4. But none of the more than 31,000 fans had left Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, nor was there any doubt about what they wanted to see. The crowd booed loudly when Garber, who had petitioned Cox to stay in the game so that he could face Rose again, fell behind 2 and 0. Still Garber wouldn’t give in, throwing a changeup off the plate that Rose fouled back. Garber got another strike, and then, on 2–2, went back to the changeup—his out pitch. The ball came in four inches outside, but Rose, fearing a walk, swung. And missed. The game was over. The streak was over. Forty-four. And now Garber leapt into the air, his arms outstretched, and catcher Joe Nolan rushed out to embrace him. Rose shot Garber a look, blew a bubble with his gum and went inside.

The scoreboard urged the crowd to chant “Ge-no, Ge-no,” to celebrate the victorious reliever, but the Atlanta fans weren’t having it. “Pete, Pete, Pete,” they called, until Rose, now stripped down to a red T-shirt adorned with the words

HUSTLE MADE IT HAPPEN

, came out and waved.

“I was in the clubhouse in my regular clothes by then,” says McWilliams, “And someone told me to go into the pressroom. So I did and I was just sitting there at the end of a table. The room was crammed with media but no one asked me a thing. After a few minutes Pete came in and asked me to scoot over, and he sat down beside me. He was kind of ticked off that Garber had thrown him a changeup. He said Garber had been pitching that at bat like it was Game 7 of the World Series.

“Then Pete was just rolling along with the reporters, ripping off one-liners, cracking people up, it was neat to see,” says McWilliams.

3

“He said some complimentary things about my pitching, which was really nice. I was just sitting there quietly in a sport jacket. I had bushy hair that you wouldn’t have seen on the field under my cap and after a while one of the people in the media picked up on the fact that Pete had no idea who I was. He said, ‘Hey, Pete, would you know Larry McWilliams if he were sitting right next to you?’ Well, there was a pause and you could just see the wheels start to turn in Pete’s head real fast. Then he turned to me and said, ‘Oh, is that

you?

’ ”

McWilliams, who would end up pitching 13 seasons and winning 78 games, recalls that as a “pinnacle moment for me, this was the night I had the most impact on the game of baseball.” Garber, now running a chicken farm in Lancaster, Pa., gets calls from reporters every August, around the anniversary of the day he stopped the streak. “People don’t let me forget it,” Garber says, and adds that he has no regrets about the changeup that he chose to throw, nor the location where he chose to throw it. Rose doesn’t complain about that anymore either.

Though DiMaggio’s record had been so visible, shimmering in the distance and dropped into nearly every mention of Rose as the streak of 1978 wore on, the record had not really been threatened. When Rose passed the 40-game mark, the president of Dartmouth College, the renowned philosopher and mathematician John G. Kemeny, did some computing and proclaimed that DiMaggio’s streak was safe for “at least another 500 years.”

Even Rose, who in the aftermath of the 45th game finally admitted to having “been under strain” and to feeling the daily pressure mount along with the size of the streak, never regarded DiMaggio’s achievement as quite in his sights. On the night he hit in his 43rd straight, Rose declared that after catching Keeler he would turn his attention to Sidney Stonestreet. “He played for the Rhode Island Reds in the Chickenbleep League,” Rose explained. “He hit in 48 straight games way back when. You probably never heard of him. I just invented him.” Staring out at DiMaggio’s record, two weeks of ball games away, was too much even for Rose. He had needed to create another goal for himself, something more plausible that could push him and sustain him along the way.

________

1

Dozens of people say things like this to Rose every day. His banishment from baseball in 1989 for having bet on the sport while managing the Reds rendered him, according to Hall of Fame bylaw, ineligible for induction. For millions of fans, Rose’s continued exclusion from Cooperstown is keenly felt as an injustice.

2

Subsequent research has given Keeler a 45-game, two-season streak, crediting him with one game at the end of the 1896 season to go with 44 straight at the start of 1897.

3

When Rose was asked by

The Washington Post

that night whether all the interviews and media obligations he’d handled in recent weeks had made him lose sleep, he replied, “Those aren’t interviews, they’re conversations. [And] reporters don’t make me lose sleep. I’m not sleepin’ with any of them.”

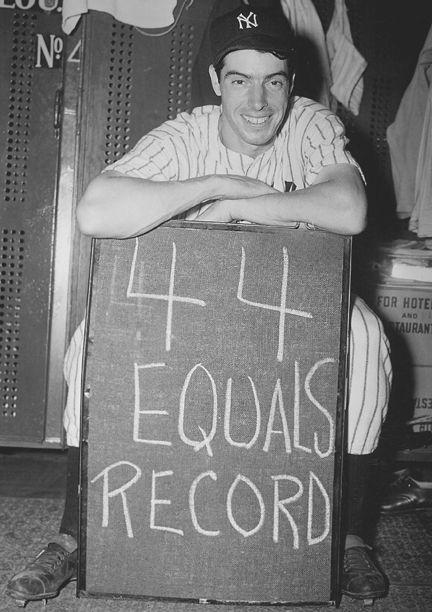

DiMaggio during Game 41 of the streak, after tying Sisler’s mark

DiMaggio during Game 41 of the streak, after tying Sisler’s mark

Photograph by Corbis

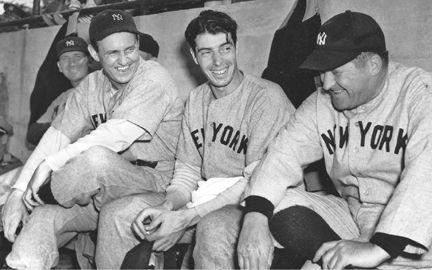

DiMaggio with pal Lefty Gomez (left) and manager Joe McCarthy

DiMaggio with pal Lefty Gomez (left) and manager Joe McCarthy

Photograph by San Antonio Light/Texas Institute of Culture/National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

The bride Dorothy, with Rosalie DiMaggio (far right) looking on

The bride Dorothy, with Rosalie DiMaggio (far right) looking on

Photograph by Bettmann/Corbis

DiMaggio and the rookie Phil Rizzuto

DiMaggio and the rookie Phil Rizzuto

Photograph by Bettmann/Corbis

Dorothy and Joe on the terrace of the West Side apartment

Dorothy and Joe on the terrace of the West Side apartment

Photograph by Bettmann/Corbis

DiMaggio reaches the Wee Willie Keeler milestone

DiMaggio reaches the Wee Willie Keeler milestone

Photograph by Corbis

American Beauty