1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (32 page)

Read 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War Online

Authors: Benny Morris

BOOK: 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

5.63Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

And during the first few days, there were even more serious problems. A twelve-year-old girl was raped by soldiers, and there were a handful of cases of attempted rape.210 The bodies of fifteen Arabs were found on a Jaffa beach, apparently executed by Haganah troops or the HIS.211 Gradually matters improved. But the harassment of Arabs and the vandalization oftheir property appears to have ended only in August.

The mass flight from the towns and villages of Palestine at the end of April triggered anxiety and opposition among the Arab leaders. Victor Khayyat, the Haifa notable, who then toured the Arab capitals, was told by the prime ministers of Syria and Lebanon of their displeasure,212 and in the first week of May, apparently in coordination with the British, the Arab leaders launched a campaign to persuade the refugees to return. The emphasis was on young, able-bodied males. On S May King Abdullah publicly called on "every man of strength and wisdom ... who has left the country, let him return to the dear spot. No one should remain outside the country except the rich and the old." He thanked those who had remained in Palestine "in spite of the tyranny now prevailing."213 A few days before, he had specifically pressed bedouin refugees from the Beisan (Beit Shean) Valley to return.214 On S -7 May, the ALA, in radio broadcasts from Ramallah and Damascus, forbade villagers from leaving, threatening that their homes would be demolished and their lands confiscated. Inhabitants who had fled were ordered to return.21S The broadcasts were monitored by the Haganah: "The Arab military leaders are trying to stem the flood of refugees and are taking stern and ruthless measures against them."216

At the same time, the British appealed specifically to the Arabs of Haifa to return to their homes; the AHC joined the campaign in the second week of May. Faiz Idrisi, the AHC's "inspector for public safety," ordered Palestinian militiamen to fight against "the Fifth Column and the rumor-mongers, who are causing the flight of the Arab population." The AHC specifically ordered officials, doctors, and engineers to return.217

The fall of Arab Tiberias and Arab Haifa cleared the way for a further, major Haganah offensive, the conquest of the villages of Eastern Galilee and the area's main town, Safad. A Syrian-Lebanese invasion was expected and clearing the rear areas of actively or potentially hostile Palestinian Arab basesthat could facilitate the invasion-became imperative. Yigal Allon, the Palmah OC, had reconnoitered the area in a spotter aircraft on 21 April and the following day recommended that the Haganah launch a series of operations, in line with Plan D, to brace for the invasion: Eastern Galilee had to be pacified, and the Arab inhabitants of the towns of Beit Shean (Beisan) and Safad had to be "harassed" into flight.218 The HGS agreed, and Allon was put in charge. The orders initially defined the objective as "taking control of the Tel Hai area and its consolidation in preparation for [the] invasion."219 Two battalions, the Palmah's Third and Golani's Eleventh, as well as local militia contingents, were to take part.

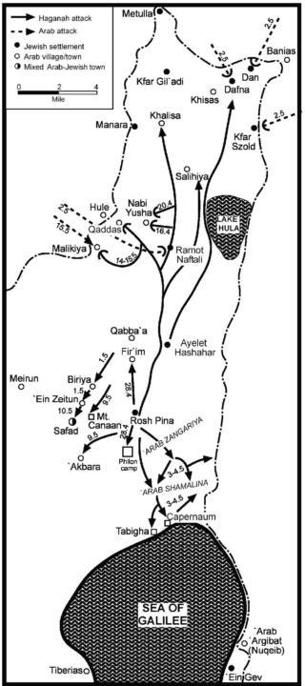

By permission of Carta, Jerusalem

Operation Yiftah, Galilee Panhandle and Safad, April-May 1948

The immediate trigger to Operation Yiftah, as it was to be called, was the staggered pullout of Britain's forces from Eastern Galilee from 15 to z8 April. Both sides rushed to occupy the abandoned Tegart forts and army camps or to eject occupying enemy forces. Operation Yiftah was preceded by stubborn, if abortive, Palmate attempts, on 16 and zo April, to take the Nabi Yusha police fort.220 The fort dominated the Hula Valley from the heights to the west.

Yiftah proper got under way on 28 April, with the Palmah occupation of the Tegart fort in Rosh Pina and the nearby army camp. On 3-4 May, the Palmah's First Battalion, in a suboperation named mivtzcz mutate (Operation Broom), cleared of Arab inhabitants-mainly the Arab al-Shamalina and Arab al-Zangariya bedouin, who for weeks had sniped at Jewish traffic along the main south-north road-the area between the Sea of Galilee and Rosh Pina: "The tents were burned and most of the houses were blown up."221 The Palmate had defined the aim as "the destruction of bases of the enemy ... and to destroy points of assembly for invading forces from the east [and] ... to join the lower and upper Galilee with a relatively wide and safe strip" of territory.222 A Catholic priest, Boniface Bittelmeier, described what he witnessed: "There was a terrible explosion in Tabigha [on the northwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee]. We rushed out and saw pillars of smoke rising skyward. House after house was bombed and torched ... smoke and fire were visible; in the evening, the `victors' returned [to base?] with trucks loaded with cattle. What they couldn't take they shot."223 In parallel, mortars were used to neutralize and clear a cluster of villages (Fir'im, Mughar al-Kheit, Qabba a) north of Rosh Pina,224 securing the road to the Galilee Panhandle, where, on 1-2 May, armed bands from Syria had attacked the kibbutzim Dan, Dafila, Kfar Szold, and Lehavot Habashan and ALA forces from Lebanon were attacking Kibbutz Ramot Naftali.225

But all this was merely a prelude to the battle for Safad, the strategically important mixed town that served as the "capital" of Eastern Galilee. Safad, with fifteen hundred Jews and ten to twelve thousand Arabs with a tradition of anti-Yishuv violence, was evacuated by the British on 16 April. They handed over to the Arabs the two dominant positions-the hilltop "Citadel" at the center of town and the large Tegart fort on Mount Canaan, to the east. That night the Arabs assailed the Jewish Quarter. The local Arab militia, of two hundred men, had been joined by more than two hundred ALA troops and Jordanian volunteers; the Haganah contingent, of some two hundred men and women, had been reinforced by an oversized Palmah platoon. The Jews drove back the Arab attack, and the Arab militias began to fall apart.226

The town's largely ultra-Orthodox Jewish community still feared annihilation.227 And the Arab town's militia commander, the Syrian al-Hassan Kam al-Maz, seemed to give credence to their fears. He cabled Adib Shishakli, the ALA regional commander: "Morale is [still] very strong, the young are enthusiastic, we will slaughter them."228

But the tables were beginning imperceptibly to turn. Turf struggles created bad blood between the various Arab militias. Shishakli replaced Kam alMaz with the Jordanians Sari al-Fnaish and Amil Jmai an, who Kam al-Maz charged were "selling out to the Jews."229 Kam al-Maz and his men left, and the remaining militiamen complained of a shortage of ammunition. 230 Operation Broom then cut Arab Safad off from any hope of aid from Syria.

On i May, Palmah Third Battalion troops, in a separate suboperation, captured two villages north of Safad, Biriya and `Ein Zeitun, cutting off the town from the west. The troops executed several dozen male prisoners from `Ein Zeitun in a nearby wadi.231 Palmah sappers proceeded to blow up the two villages as Safad's Arabs looked on. The bulk of the Third Battalion then moved into the town's Jewish Quarter and mortared the Arab quarters.232 Many Arabs fled, wending their way down Safad's eastern slopes toward the Syrian border.

Taken together, these operations, coming after Deir Yassin and the fall of Tiberias and Haifa, discouraged the population and paved the way for Safad's fall. An abortive Third Battalion attack on the Citadel on 6 May,233 which included a mortar barrage, had the same effect.234 Already on 5 May the commanders of the Jordanian volunteer force radioed al-Qawuqji that if reinforcements, including artillery, failed to arrive, they would leave; the town could not hold out for "more than two hours."235

After 6 May, the "terrified" Arabs sought a truce. Allon, who visited the Jewish Quarter the next day, rejected terms,236 and the Arab states failed to provide the militias with assistance (apart from pressing Britain to intervene, which Whitehall declined to do). Allon ordered Moshe Kelman, the Third Battalion OC, to renew the assault and solve the problem of Safad immediately; the pan-Arab invasion was just days away. 2-17 Shishakli, who also visited the town, ordered an attack on io May and reinforced the militias with a further company of Jordanians. Meanwhile, his artillery began intermittently to shell the Jewish Quarter from a nearby hill.

Some local Jews sought to negotiate a surrender and demanded that the Haganah leave town. But the Haganah commanders were unbending and at 9:35 rM, 9 May, preempted Shishakli, launching a multipronged attack. The timing was immaculate: a few hours earlier, al-Fnaish, Jmai`an, and much of the Jordanian contingent had slipped out of town, severely undercutting the Arab defenses. (Some Arabs subsequently charged al-Fnaish with treachery, and he was briefly jailed in Syria. But some sources claim that the Jordanian volunteers were ordered to leave by King Abdullah, who perhaps sought to prevent a Husseini victory that might result in the installation in Safad of a mufti-led Palestinian government.)2ss

The Palmahniks, backed by Davidka and 3-inch mortars, and PIATs, that night, under a heavy rain, managed to take the Citadel as well as the town's police fort (where the battle was particularly prolonged and severe) and other Arab positions, including the village of Akbara, just south of town.239 The Haganah successes and the Davidka bombs, which exploded with tremendous noise and a great flash, triggered a mass panic, "screams and yells."240 According to Arab sources, cited by an HIS document, the first Davidka bomb, which killed "13 Arabs, most of them children," triggered the panicintended by the Palmah commanders when unleashing the mortars against the Arab neighborhoods.241 A rumor then spread that the Jews were using "atom" bombs (which, some Arabs believed, had sparked the unseasonably heavy downpour).242 A Haganah scout plane, flying overhead, reported "thousands of refugees streaming by foot toward Meirun"; another report depicted the inhabitants "loaded down with parcels, women carrying their children in their arms, some going by foot, others on ass and donkeyback."243 The Arab neighborhoods, literally overnight, turned into a "ghost town," and the Jewish inhabitants went "wild with joy and danced and sang in the streets."244 The Palmahniks spent ,o-11 May scouring the abandoned neighborhoods. During the following weeks, the few remaining Arabs, most of them old and infirm or Christians, were expelled to Lebanon or transferred to Haifa.24s

During late April and early May, a handful of villages along the Syrian border were ordered, by the Syrian authorities or local Arab commanders, to evacuate their houses or to move out their women and children, either to facilitate their takeover by Arab militiamen or to clear the area in advance of the impending invasion.246 This dovetailed with the Yiftah Brigade's efforts, immediately after the fall of Arab Safad, to clear out the villagers from the Hula Valley and Galilee Panhandle in advance of the expected invasion. According to Allon, Safad's demise had badly shaken the morale of the villagers; the Palmah sought to exploit the effect:

We only had five days left ... until IS May. We regarded it as imperative to cleanse the interior of the Galilee and create Jewish territorial continuity in the whole of Upper Galilee. The protracted battles had reduced our forces and we faced major tasks in blocking the invasion routes. We therefore looked for a means that would not oblige us to use force to drive out the tens of thousands of hostile Arabs left in the [Eastern] Galilee and who, in the event of an invasion, could strike at us from behind. We tried to use a stratagem that exploited the [Arab] defeats ... a stratagem that worked wonderfully.

I gathered the Jewish mukhtars [headmen], who had ties with the different Arab villages, and I asked them to whisper in the ears of several Arabs that giant Jewish reinforcements had reached the Galilee and were about to clean out the villages of the Hula, [and] to advise them, as friends, to flee while they could. And the rumor spread throughout the Hula that the time had come to flee. The flight encompassed tens of thousands. The stratagem fully achieved its objective . . . and we were able to deploy ourselves in face of the [prospective] invaders along the borders, without fear for our rear.247

To reinforce this "whispering," or psychological warfare, campaign, Allon's men distributed fliers, advising those who wished to avoid harm to leave "with their women and children. "248

During the following days villages that had not been abandoned, or had been abandoned briefly and then partially refilled with returnees (often because the refugees began to suffer from "hunger"),249 were conquered, the battalion HQs usually instructing the attacking units to expel the inhabitants.250 Palmah troops also mounted raids into Syria and Lebanon, blowing up, among other targets, the mansion, near Hule, ofAhmad al-As`ad, a leading south Lebanese Shiite notable.251 A newly established bedouin unit, commanded by Yitzhak Hankin, took part in the operations.252 Yet many Hula Valley villagers who fled or were driven out did not cross the border but encamped, often in swampland, along the Palestine side of the line, fearing that if they crossed into Syria they would be conscripted by the Syrian Army.253 By the fourth week of May, the Palmah was "systematically torching the Hula [Valley] villages."254

Other books

The Gift of Shayla by N.J. Walters

Autumn: The City by David Moody

A Wedding Story by Susan Kay Law

The Other Normals by Vizzini, Ned

Freed by Brown, Berengaria

Peckerwood by Ayres, Jedidiah

Fallen Star by Cyndi Friberg

Snipped in the Bud by Kate Collins

An Infidel in Paradise by S.J. Laidlaw

The Boy Book by E. Lockhart