1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (26 page)

Read 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War Online

Authors: Benny Morris

BOOK: 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

10.42Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

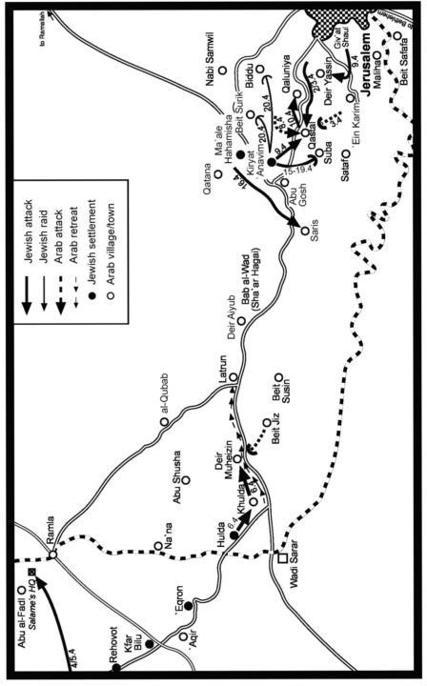

In retrospect, Operation Nahshon marked the start of the implementation of Plan D. The operational order for Nahshon, issued by Avidan on 4 April, defined the objectives as (i) "to push [a] convoy" from Kibbutz Hulda to Jerusalem and (2) "to open the road to Jerusalem by means of offensive operations against enemy bases" along the road to assure the passage of future convoys. The order's preamble noted that "all of `shem's' [that is, the Arab] villages along this route are to be regarded as enemy assembly points or bases of operation."39 Most of these villages lay in the territory designated in the partition resolution for Palestinian Arab sovereignty-which meant that securing the road or "Corridor" to Jerusalem would involve an expansion of the prospective Jewish state's territory.

In effect, the operation began on the night of 2-3 April, even before the operational order was issued. A Palmah company, reacting to clashes between Jewish and Arab militiamen in the Motza area, conquered the small village of al-Qastal, just west of Jerusalem, overlooking the road. The company met negligible resistance and suffered no casualties.40 Two days later, on the night of 45 April, a company of Giv'ati Brigade troops blew up the four-story headquarters in an orange grove near Ramla of Hassan Salame, who commanded the irregulars at the western end of Nahshon's operational area. Though the commander emerged unscathed, some two dozen Arabs and a German officer who served as Salame's adviser died in the explosion. The operation dealt a mortal blow to Salame's reputation and to Arab morale countrywide; Arabs fled from nearby villages.4' Givati had suffered only three lightly wounded.42

The operation effectively neutralized the main Arab band at the western end of the Jerusalem Corridor, paving the way for the Haganah conquest, on 6 April, of the Arab villages of Khulda and Deir Muheizin. With these and alQastal secured, the Haganah successfully relaunched the sixty-vehicle convoy, with reinforcements, food, fuel, and ammunition, from Kibbutz Hulda, where it had been stuck for a week, toward the capital. It reached West Jerusalem the following day, cheered by onlookers lining the sidewalks.

But if the destruction of Salame's headquarters grabbed instant, large headlines, the conquest of al-Qastal triggered major long-term effects. The Haganah garrisoned the empty village with a second-line infantry platoon from the `Etzioni Brigade. Some of the troops had no combat experience; others knew no Hebrew. But HGS had misread the situation. During the following days Jerusalem Haganah and Palmah commanders bickered over who was responsible for holding and/or reinforcing al-Qastal. But Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini, the Arab Jerusalem Hills sector commander, understood its importance: al-Qastal dominated the western entrance to the city. Hundreds of militiamen and Iraqi volunteers massed to retake the village; irregulars arrived from as far away as Nablus. They sniped at the defenders and slowly inched toward al-Qastal. British armored cars initially helped the `Etzioni troops with cannon fire but then withdrew. For the next three days, the 'Etzioni platoon was hit with mortars and machine guns from the surrounding hills. They continuously pleaded for reinforcements. But none materialized, though Haganah light aircraft periodically overflew the area and (ineffectively) lobbed grenades and strafed the Arabs. The `Etzioni men held on.

Meanwhile, Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini journeyed to Damascus to plead for ammunition and arms, especially artillery. He argued that al-Qastal and the road were crucial. But he came away empty-handed. At one point, he reportedly chided Ismail Safwat, the head of the League's Military Committee, after flinging a map of Palestine in his face: "You traitor. History will condemn you. I am returning to al-Qastal, with or without heavy arms. I'll take al-Qastal or die fighting." That night, he composed a poem for his sevenyear-old son, Faisal (who was to serve in the 199os as the PLO's Jerusalem affairs "minister") :

He then set off for Palestine to organize what he hoped would be the decisive assault.

On the night of 7-8 April hundreds of irregulars, led by Ibrahim Abu Diya, of Surifvillage, reached al-Qastal's perimeter houses. The `Etzioni unit fought them off with grenades and submachine guns. The assault bogged down, and the attackers withdrew.

Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini had watched from a nearby hill but could see little. Just before dawn, he climbed the al-Qastal slope with two or three aides, one of them his deputy Kamal `Erikat, either to see what was happening or to lead a fresh assault. Fog enveloped the hilltop village. Abd al-Qadir and his colleagues wended their way through the first outlying houses. As they approached the mukhtar's house, an `Etzioni sentry mistook them for the first of long-promised reinforcements and hailed them in Arabic slang in common use in the Haganah: "Up here boys." Abd al-Qadir called back, in English: "Hello boys." The sentry, Meir Karmiyol, sensed that it was an Arab's English-or he may have seen something amiss. He fired off a burst in the direction of the voices. Abd al-Qadir fell to the ground and his aides fled down the hillside. `Abd al-Qadir muttered: "Water, water." A Haganah medic approached and tended him, but he expired. Karmiyol looked through alHusseini's clothes and discovered documents, a miniature Qur'an, gold pens, an ivory-handled pistol, and a gold watch. He realized that he had bagged a big shot. Yet the man's identity was still unclear.

Meanwhile, al-Qastal was peppered with sniper fire. The weary defenders expected a renewed assault momentarily. But the airwaves were soon filled with Arabic chatter and anxiety about their missing commander. Soon convoys with reinforcements were making their way to the area from Hebron and Nablus. They were bent on saving, or retrieving the body of, their leader. "I saw thousands of Arabs. Buses, trucks and donkeys brought them from Suba," one of the al-Qastal defenders later recalled.44

By noon, the village was under heavy attack. The defenders were low on ammunition and exhausted. A platoon of Palmah soldiers at last reached the area via the Jerusalem road. But it was too late. The `Etzioni troops had had enough. Many fled down the slope northward, toward the road-just as the Palmahniks, led by Nahum Arieli, were climbing up. The Arabs, coming from the south and west, "attacked like madmen."45 They occupied some houses and laid down a barrage of mortar and machine gun fire. Arieli managed to reach the `Etzioni command post. But dozens of Haganah and Palmah men were already dead or wounded, and a mass of Arab militiamen was pressing up the alleyways toward the mukhtar's house.

Arieli ordered his men, and the remaining `Etzioni troops, to retreat eastward. As they withdrew, the dead and dying were left on the slopes. There was a lull in the shooting. "I saw a lot of Arabs, like flies, and then realized why it was quiet. They had taken the village. They started to celebrate.... I fled to the orchard [at the base of the hill] with part of my squad," an `Etzioni veteran recalled.46 Arabs began to push down the slope, giving chase. Arieli and a handful of other officers took up positions nearby to cover the retreat. Their bodies were later found there, either felled by Arab bullets or by their own hand, with grenades, to avoid capture.

The Arabs spent the afternoon hunting and killing stray and wounded Haganah men. Eventually they found what they were looking for-Husseini's body. Arab command and control-and morale-broke down; they had lost their leader, and several of his lieutenants, including `Erikat and Abu Diya, were wounded. Abd al-Qadir's body was taken to Jerusalem and the following day, a Friday, was buried on the Temple Mount next to his father, Musa Kazim al-Husseini, the late mayor. The massive procession included most of East Jerusalem's notables, foreign consuls and Arab Legion officers, as well as most of those who had fought at al-Qastal, who abandoned their posts and accompanied the body to Jerusalem. "The whole country walked after his coffin.... Not a shop was open," wrote one diarist.47 Abu Diya spoke over the open grave; Haj Amin al-Husseini, in Cairo, sent a eulogy. It was read out: "One thing shall not die, Palestine."48 There was an eleven-cannon salute.

Meanwhile, Yadin-set on sending the empty convoy back from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv to reload-ordered the Palmah to retake al-Qastal, "immediately," and to reopen the road. The Harel Brigade officer in command, Yosef Tabenkin, balked, arguing insufficient forces. Yadin was enraged. Tabenkin backed down. Just before dawn, 9 April, two of Tabenkin's companies stormed into al-Qastal-which they found completely deserted, save for dozens of corpses.49 The Palmahniks buried the dead. Some of the Jewish corpses had been badly mutilated.-50 The Palmahniks blew up most of the houses and organized a perimeter defense. The convoy, meanwhile, wound its way down the hills to Hulda, unmolested.

At al-Qastal, between 3 and 9 April, the Israelis had lost seventy-five men. The Arabs had lost ninety, but they included the Palestinian Arabs' foremost military commander. And they had lost a crucial battle and a vital strategic position on the road to Jerusalem.

The original operational order of 2 April for the conquest of al-Qastal had forbidden the Haganah troops from razing the village. In the same spirit, Yadin had initially instructed the Nahshon commanders to "occupy [sites], if possible, near villages and not to conquer them."51 But the follow-up order, of 8 April, to recapture al-Qastal, specifically ordered the destruction of its houses. This was indicative of the radical change of thinking in the HGS. In line with Plan D, Arab villages were henceforward to be leveled to prevent their reinvestment by Arab forces; the implication was that their inhabitants were to be expelled and prevented from returning.

Simultaneously with the recapture of al-Qastal, IZL and LHI units, marginally assisted by the Haganah, conquered the village of Deir Yassin, between al-Qastal and Jerusalem. The village was militarily insignificant, and it was not much of a battle-but it proved to be one of the key events of the war.

The relations between Deir Yassin and the adjacent Jewish Jerusalem neighborhood of Giv at Shaul had been checkered. In 1929, gunmen from Deir Yassin had attacked the neighborhood. In August 1947 and again the following January representatives of the two communities had signed 1nutual nonaggression pacts. The villagers subsequently turned away roving Arab irregulars, denying them aid, a haven, and a base of operations.52 But it is possible that a band of Iraqi or Syrian irregulars bivouacked in the village just before its fall, and irregulars from the village reportedly fired on West Jerusalem and participated in the battle for al-Qastal.

When the battle for al-Qastal erupted, the Jerusalem Haganah command asked the IZL for assistance. The IZL chiefs declined, saying they wanted to launch an independent operation. In the end, they proposed to conquer Deir Yassin, and David Shaltiel, the Jerusalem Haganah OC, agreed. But he demanded that the IZL afterward hold the site permanently. The prospective operation loosely meshed with the Nahshon objective of securing the western approaches to Jerusalem. In planning their attack, the IZL and LHI commanders agreed to expel the inhabitants; a proposal to kill all captured villagers or all captured males was rejected. According to Yehuda Lapidot, the IZL deputy commander during the battle, the troops were specifically ordered not to kill women, children, and POWs.

Other books

An Uncommon Grace by Serena B. Miller

With His Consent (For His Pleasure, Book 13) by Favor, Kelly

A Night at the Operation by COHEN, JEFFREY

The Dog by Joseph O'Neill

A Little Help from Above by Saralee Rosenberg

Elizabeth M. Norman by We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Nurses Trapped on Bataan

Showstopper by Lisa Fiedler

Brutal Revenge by Raven, James

Seaborne by Irons, Katherine