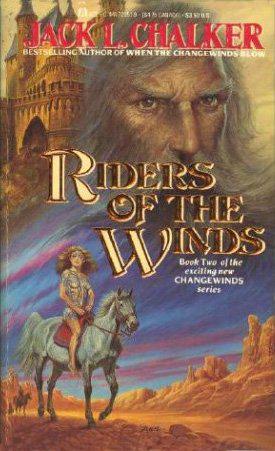

02. Riders of the Winds

Read 02. Riders of the Winds Online

Authors: Jack L. Chalker

RIDERS OF THE WINDS

Copyright © 1988 by Jack L. Chalker.

e-book ver. 1.0

For Ted Cogswell, and Polly Freas, and Bea Mahaffey, and Alice "Tip" Sheldon,

and too many other old friends who left this outplane while I was writing this. I owe you all, but too many of you are

missing when I return to this reality, and contrary to

natural law, there are far too many vacuums where

once special brightness dwelt.

PROLOGUE

The Shape of Things

When the changewinds blow, out from the Seat of Probability and across the worlds they themselves created, they are capricious things, at once random and consistent, yet they obey their own spectral meteorology.

The Changewinds' breath touched the formative Earth when it was but a cooling mass of molten rock, its own formation caused by a previous storm hitting in the void, and within that mass was sufficient moisture to cause the great clouds formed from condensation. The winds had less to draw them, then, so they let it alone for thousands of years. It was one hell of a rainstorm.

The Changewinds returned to touch the new Earth when it was still soup, and the conditions arose for the joining of acids and proteins just so. It was not planned that way; it simply had to happen someplace under the laws of probability, which are the only laws the Changewinds recognize.

Later Changewinds, far weakened this far from the Seat of their origin, none the less gently caressed the still-developing mass sufficient to create the early creatures of the sea and establish the developmental pattern that led in the end to the vast jungles and the reign of great reptiles and amphibians. Another, perhaps stronger, storm dismissed them as coldly and capriciously as they had been made masters of the world, and allowed for the rise of mammals.

Why did the ape line develop better than the rest? Why did one branch develop intelligence and tools and eventually civilization of sorts? Well, why not? It might as well have been them as anything else. And the same sort of thing had happened on a large number of probable worlds between the Earth we know and the Seat, creating both the same sorts of creatures and very different ones. Our world is far from the Seat, and younger; the others developed earlier, as ones beyond developed later than we, but those vast civilizations and worlds which developed in between created a buffer between the younger worlds and the Seat, increasingly dense, protecting our world as mountains and jet streams and seas and air masses protect us from weather, absorbing much of the energy.

A great storm moves across the land wreaking havoc as it comes, until it hits the mountains, the great, impressive barriers of nature. Crossing those mountains requires ten, a hundred, a thousand times the energy of crossing vast plains and oceans. A stubborn, particularly violent storm might make it, but if it does it will be so weakened that it will be quite ordinary to those living on the far side of the range. Or it might be diverted, attempting to go around the mountain barriers, and hitting elsewhere or spending itself in a long, futile journey.

So, too, the Changewinds are weakened and diverted by the worlds between, thus aiding the new humanity from suffering as capriciously as the dinosaurs sudden and terrible extinction. We owe the dinosaurs a debt, for we might have been first, when protections were weaker, and they come later.

But though the storm that crosses the mountains might be a pale shadow of its former self, it is still a storm. It still wets or whitens the ground, changes temperature and humidity, causes slippery roads and accidents and changed plans, or perhaps causes a crop to be saved or a drought to be ended. Even though it is not large or grand, it still might have far-reaching effects, if you must drive on that rainy day on some slippery road instead of on dry asphalt under a comforting sun and blue sky. Without the storm you might not have lost traction on that hill, might not have hit the post or the oncoming car, or been in the path of another, causing a tragic chain.

One little storm, no matter how tiny it may be, can have great repercussions.

A great Changewind storm was a mere ripple in the mathematics of probability by the time it touched Troy, but Troy fell just the same when it succumbed to a pretty ridiculous trick. Another ripple placed Alexander where he could conquer the known world, and took him from that world too young to do more than that. Just a tiny whisper, a slight rippling in the leaves, but Caesar dies because all goes exactly right, and the assassins then are beaten because nothing does. Just a mere sigh of the wind chimes, but a carpenter turned rabbi, one of hundreds of self-proclaimed prophets and messiahs of the times, becomes a force that lasts for thousands of years because everything, even his death, goes right. Such things can happen, even to a single holy man among multitudes in India or an illiterate nomad near Medina in Arabia. For every one that founded a great religion and affected millions there were thousands who did not. Why them? Were they what they claimed, or not? It makes no difference to the Changewinds, except to remember that they worship probability alone, and so any one of these just might have been for real . . .

The winds are like that.

Wars, and peace; revolution and reaction; darkness and renaissance; invention and ignorance . . . all are the same to the Changewinds, and one is just as good as the other. Causes rarely win or lose on their merits, but on the smallest of things.

"For want of a nail the shoe was lost . . ."

The Changewinds touch the ordinary and make them great, and touch the great and make them failures. A Corsican officer becomes Emperor of France. A Hainanese librarian unifies mainland China under a communism of his own unique design. A German Jewish economist believes he finds the key to human history and dominates radicalism but never controls it. The son of a superintendent of schools, a former seminary student, and a Russian Jewish scholar unite in the name of the proletariat they never were and bring a new order to Russia in the name of a man who said that communism might never be possible there. A failed painter of Viennese postcards moves to Bavaria and becomes the leader of a ragtag collection of disaffected radicals and old soldiers and in ten years is acclaimed dictator of a new Germany. The probability of this, all things

considered, is next to none, but so long as it is not zero the winds might manage it.

There are still impossible things when the Changewinds blow, but nothing is improbable.

And everyone who lives a life is eventually touched by at least a small one, some many times; if not in day-to-day life then in dreams, mythologies, fantasies, gods, and demons, which are echoes, remnants, of those lands through which the winds must pass.

All the universes created by the winds exist in time and space distanced enough so that the creatures of those universes live in egocentric ignorance of the nature of their true birth and that which touches and shapes their large and small destinies. This infinite stream of universes rarely touches another reality and even less often overlaps. It does happen, of course. Benjamin Bathhurst walked around a horse in full view of a dozen men and was never seen again. A wild wolf-boy appears mysteriously as a young teen in a German forest. How came he there, and from where? One place has a sudden rain of frogs, and another has a solid churchman explode and burn while sitting in his easy chair reading the paper. From whence came the bolt that ignited him, for there is no hole in the roof? These and many other puzzles do happen, but they are rare enough that rational men might dismiss them as folklore, old wives' tales, or, even when stumped for the most farfetched of rational-sounding solutions, fall back on, "There

must

be a logical explanation!"

Down, though, close to the Seat of Probability, the gravitational force of the First Cause pulls the worlds ever closer, ever more densely packed together. There might, that close in, be hundreds, even thousands of universes all so densely packed that what is the rare and bizarre overlap in the far-off universes of the rational folk is commonplace there, and one might walk from one universe to the other while hardly realizing it.

This region, the closest in to the Seat that will support any son of life as we might know it, is called by its rulers Akahlar. The Akhbreed fell here, a remnant of a powerful tribe, perhaps, in ancient times, from some world farther out, but they were first and they learned to live in and adapt to this land. Their understanding and mastery of the arcane laws that

govern such a madhouse gives them their power over all the others who have fallen since and over those universes that have the bad fortune to overlap. The Akhbreed sorcerers weave no magic in the true sense; they simply have mastery over physical laws and powers bestowed by afar different universe than our own. They maintain the rock-steady loci, great lands held fast by the sorcerers for their kings and people, and they milk the produce of a colonial empire extending over so many worlds that none of the greatest imperialist dreamers could have hoped for such power and domains. Between the loci kingdoms, though, is anywhere and anywhen for countless universes and lands. The Akhbreed navigators can pick their lands and universes and routes, but for the rest it is random, making revolution impossible and resistance futile on any large scale.

There is only one thing that even the Akhbreed fear, and that even the Akhbreed sorcerers must yield before, and that is the Changewind, which blows far more frequently and with far greater severity through Akahlar, since no Changewind, however diminished, could reach the outer universes except first it pass through Akahlar.

For countless centuries those people who must pay tribute to the Akhbreed and place those masters first before their own interests have dreamed and hoped for a deliverer.

For countless centuries the Akhbreed sorcerers have dreamed of the ultimate power, of control and direction of the very Changewinds themselves, a power that would truly make them gods over all the universes everywhere.

This is a tale of a choice of dreams, and a choice of nightmares, down, deep, where the Changewinds blow . . .

1

A Choice of Bad Roads

Clouds were rare in Kudaan Wastes; its blasted appearance, orange, furrowed hills, and deep ravines and lack of much that was the green color of life attested to that. To have two storms in a matter of days was not only unheard of, it was a prescription for disaster, since such parched lands had ground baked so hard it would run off and the flash flood might ensnare anyone or anything anywhere.

This was a small storm, forming with suddenness as such storms usually do, perhaps over some cool spot where sufficient moisture from the last rain had collected and begged to be evaporated by the harsh sun. The clouds swirled and thickened and seemed to take on a life of their own. Small flashes of energy built up within, and from the darkest part of the building thunderhead shone two tiny, deep depressions that illuminated a crimson red from the charges within, as if the cloud indeed was the protective shield or shroud of some dark and loathsome monster.

The Sudog drew its strength from the storm and took control of it, blazing eyes looking down, scouring the land. There was little wind that it did not create and little variation in the heat of the day except where its shadow fell, and so it had a relatively free hand.

It swung first west, until it found the main road leading into the Wastes, taking care not to get too close to the border where the interaction between wedges could cause unpredictable and perhaps fatal weather effects. The desert floor that was usually so flat and featureless was in full bloom, with great blood red flowers hanging from strong green vines that shot out of the soil and into the air and tried to do all that they had to do in the days perhaps even hours, before the moisture dried and they were forced once again into dormancy.

The Sudog wasted none of its energy on them, nor any of the water that kept it cohesive. If floated well over the growths and towards where the road went down deep into a canyon with steep walls and isolated bluffs, its dull red and yellow and purple rock layers thus exposed leaving part of its depth forever in shadow.