The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (23 page)

Read The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century

Within the hills, the Indians believed, lived the “below powers”—mysterious forces often represented by the bear and buffalo that could see into the future. That night as the Seventh Cavalry marched through the dusty darkness, it marched toward a destiny foreshadowed to a remarkable degree by a battle fought more than seven and a half years earlier on the plains of Oklahoma.

I

n the fall of 1868, General Sheridan recalled Custer from his yearlong suspension to lead the Seventh Cavalry in a winter campaign against the Cheyenne. Upon his return from exile, Custer proceeded to turn the regiment inside out.

For “uniformity of appearance,” he decided to “color the horses.” All the regiment’s horses were assembled in a single group and divided up according to color. Four companies were assigned the bays (brown with black legs, manes, and tails); three companies were given the sorrels (reddish brown with similarly colored manes and tails); one company got the chestnuts; another the browns; yet another the blacks; and yet another the grays; with the leftovers, euphemistically referred to as the “brindles” by Custer, going to the company commanded by the most junior officer.

It might be pleasing to the eye to assign a horse color to each company, but Custer had, in one stroke, made a mockery of his officers’ efforts to provide their companies with the best possible horses. And besides, as every cavalryman knew, horses were much more than a commodity to be sorted by color. Each horse had a distinct personality, and over the course of the last year, each soldier had come to know his horse not only as a means of transportation but as a friend. “This act,” Benteen wrote, “at the beginning of a severe campaign was not only ridiculous, but criminal, unjust, and arbitrary in the extreme.” But Custer was not finished. During his absence, he announced, the regiment had become lax in marksmanship. To address this failing, he established an elite corps of forty sharpshooters. He then named Benteen’s own junior lieutenant William Cooke as the unit’s leader.

Benteen certainly did not appreciate these moves, but there was one officer who had even more reason to view them as a personal affront. Major Joel Elliott had assumed command during Custer’s absence. Elliott, just twenty-eight, was an ambitious and energetic officer; he had also done his best to quietly undercut his former commander, and Custer, Benteen claimed, knew it. By so brazenly establishing his own fresh imprint on the regiment, Custer had put Elliott on notice.

From the start, the regiment had expected cold and snow, but the blizzard they encountered before they left their base camp on the morning of November 23 was bad enough that even the architect of this “experimental” winter campaign, General Sheridan, seemed reluctant to let them go. Already there was a foot of snow on the ground and the storm was still raging. “So dense and heavy were the falling lines of snow,” Custer remembered, “that all view of the surface of the surrounding country, upon which the guides depended . . . , was cut off.”

They were marching blind in the midst of a howling blizzard, and not even the scouts could tell where they were headed. Rather than turn back, Custer took out his compass. And so, with only his quivering compass needle to guide him, Custer, “like the mariner in mid-ocean,” plunged south into the furious storm.

They camped that night beside the Wolf River in a foot and a half of snow. The next day dawned clear and fresh. Before them stretched an unbroken plain of glimmering white, and as the sun climbed in the blue, cloudless sky, the snow became a vast, retina-searing mirror. In an attempt to prevent snowblindness, the officers and men smeared their eyelids with black gunpowder.

Two days later, November 26, was the coldest day by far. That night, the soldiers slept with their horses’ bits beneath their blankets so the well-worn pieces of metal wouldn’t be frozen when they returned them to the animals’ mouths. To keep their feet from freezing in the stirrups as they marched through a frigid, swirling fog, the soldiers spent much of the day walking beside their mounts. That afternoon they learned that Major Elliott, whom Custer had sent ahead in search of a fresh Indian trail, had found exactly that. On the night of November 27, they found Elliott and his men bivouacked in the snow.

Judging from the freshness of the trail, the Osage scouts were confident that a Cheyenne village was within easy reach. After a quick supper, they set out on a night march. The sky was ablaze with stars, and as they marched over the lustrous drifts of snow, the regiment looked, according to Lieutenant Charles Brewster, like a huge black snake “as it wound around the tortuous valley.”

First they smelled smoke; then they heard the jingling of a pony’s bell, the barking of some dogs, and the crying of a baby. Somewhere up ahead was an Indian village.

It was an almost windless night, and it was absolutely essential that all noise be kept to a minimum as they crept ahead. The crunch of the horses’ hooves through the crusted snow was alarmingly loud, but there was nothing they could do about that. When one of Custer’s dogs began to bark, Custer and his brother Tom strangled the pet with a lariat. Yet another dog, a little black mutt, received a horse’s picket pin through the skull.

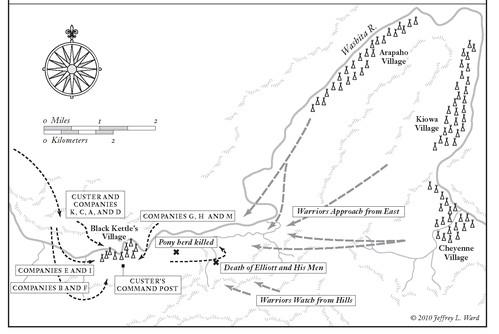

Custer and his officers observed the village from one of the surrounding hills. The tepees were clustered on a flat thirty-acre crescent just to the south of the Washita River. One of his officers asked, “General, suppose we find more Indians there than we can handle?” Custer was dismissive. “All I am afraid of [is] we won’t find half enough.”

Even though he was unsure of the exact number of tepees, Custer divided his command into four battalions. At dawn, he and the sharpshooters would attack from the north as Elliott came in from the east and another battalion came in from the south. Benteen was assigned to the battalion that was to attack from the west. The brass band, all of them mounted on white horses, were to strike up “Garry Owen” when it was time to charge the village.

As the other three battalions maneuvered into their proper places, Custer waited beneath the cold and glittering sky. For a brief hour he lay down on the snow and slept, his coat thrown over his head. By the time the first signs of daylight began to soften the edges of the horizon, he was awake and readying his officers and men for the coming attack.

The village was so intensely quiet that Custer briefly feared the tepees were deserted. He was about to signal to the bandleader when a single rifle shot erupted on the far side of the village. The time to attack was now. Soon the “rollicking notes” of “Garry Owen” were echoing improbably across the snow-covered hills, and the four battalions of the Seventh Cavalry were galloping into the village.

Custer led the charge, his big black horse leaping across the river in a single jump. Once in the village, he fired on one warrior and ran down another on his way to a small hill, where he established a command post. He had encountered almost no resistance in his charge to the hill, but such was not the case with the battalion to the west, led by Frederick Benteen. A Cheyenne teenager charged toward him with his pistol up-raised. Not wanting to shoot someone he considered a noncombatant, Benteen gestured to the boy, trying to get him to surrender, but the young Cheyenne would have none of it. Three times he fired, narrowly missing Benteen’s head and wounding his horse before Benteen reluctantly shot the boy dead.

Benteen claimed that his company did most of the hard fighting that day and “broke up the village before a trooper of any of the other companies of the Seventh got in.” He also took credit for rounding up the fifty or more Cheyenne women captives and for driving in the Indians’ pony herd of approximately eight hundred horses. “I know that Custer had respect for me,” he later wrote, “for at the Washita I taught him to have it.”

Lieutenant Godfrey returned from pursuing Indians to the east with some disturbing news. Several miles down the river was another, much bigger village, and hundreds, if not thousands, of warriors were then galloping in their direction. Custer also learned that Major Elliott had chased another group of Indians in that direction but had not yet returned. Godfrey had heard gunfire during his foray east—might it have been Elliott? Custer, Godfrey remembered, “pondered this a bit,” then said he didn’t think so, claiming that another officer had also been fighting in that vicinity and would have known if Elliott had been in trouble. And besides, they had other pressing concerns. They must destroy the Cheyenne’s most precious possession: the pony herd.

—THE BATTLE OF THE WASHITA,

November 27, 1868

—

As the surrounding hills filled up with warriors from the village to the east, the troopers turned their rifles on the ponies. It took an agonizingly long time to kill more than seven hundred horses. One of the captive Cheyenne women later remembered the very “human” cries of the ponies, many of which were disabled but not killed by the gunfire. When the regiment returned to the frozen battle site several weeks later, Private Dennis Lynch noticed that some of the wounded ponies “had eaten all the grass within reach of them” before they finally died.

Custer then ordered his men to burn the village. The tepees and all their contents, including the Indians’ bags of gunpowder, were piled onto a huge bonfire. Each time a powder bag exploded, a billowing cloud of black smoke rolled up into the sky. All the while, warriors continued to gather in the hills around them.

Black Kettle’s village contained exactly fifty-one lodges with about 150 warriors, giving the regiment a five-to-one advantage. But now, with warriors from what appeared to be a huge village to the east threatening to engulf them, the soldiers were, whether or not Custer chose to admit it, in serious trouble.

The scout Ben Clark estimated that the village to the east was so big that the odds had been reversed; the Cheyenne now outnumbered the troopers by five to one. But Custer wanted to hear none of it. They were going to attack the village to the east.

Clark vehemently disagreed. They were short of ammunition. Night was coming on. Victory was no longer the issue. If they were to get out of this alive, they must be both very smart and very lucky.

In

My Life on the Plains,

Custer took full credit for successfully extracting the regiment from danger. Ben Clark had a different view, claiming that he was the one who devised the plan. The truth is probably somewhere in between: Once Clark had convinced Custer that attacking the other village was tantamount to suicide, Custer embraced the notion of trying to outwit the Cheyenne.

It was a maxim in war, Custer wrote, to do what the enemy neither “expects nor desires you to do.” The Seventh Cavalry appeared to be hopelessly outnumbered, but why should that prevent it from at least pretending to go on the offensive? A feint toward the big village to the east might cause the warriors to rush back to defend their women and children. This would give the troopers the opportunity to reverse their field under the cover of night and escape to safety.

With flags flying and the band playing “Ain’t I Glad to Get Out of the Wilderness,” Custer marched the regiment toward the huge village. Even before setting out, he’d positioned the Cheyenne captives along the flanks of the column. Sergeant John Ryan later remembered how the panicked cries of the hostages immediately caused the warriors to stop firing their weapons.

On they marched into the deepening darkness. Without warning, Custer halted the regiment, extinguished all lights, and surreptitiously reversed direction. By 10 p.m., they’d returned to the site of the original battle (where the bodies of Black Kettle and his wife still floated in the frigid waters of the Washita). By 2 a.m., the troopers had put sufficient distance between themselves and the Cheyenne that Custer deemed it safe to bivouac for the night.

Several days later they returned to their base camp, where General Sheridan declared the operation a complete success. There was one nagging question, however. What had become of Elliott and his men? Already Benteen had begun to question the scouts concerning what Custer had known about the major’s disappearance. One of the officers told how, before galloping off to the east, Elliott had waved his hand and melodramatically cried, “Here goes for a brevet or a coffin!” Elliott had clearly left Black Kettle’s village on what Benteen termed “his own hook.” To hold Custer accountable for the officer’s death seemed, to many, unfair—but not to Frederick Benteen.