The Dancing Wu Li Masters (38 page)

Read The Dancing Wu Li Masters Online

Authors: Gary Zukav

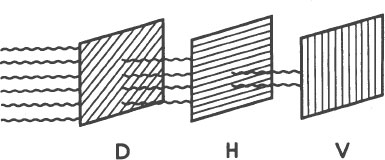

With this in mind, we come now to the third filter. Align the third filter so that it polarizes light

diagonally

and place it in front of the horizontal polarizer and the vertical polarizer. Nothing happens. If the first two filters (the horizontal and the vertical polarizer) block all the light, the addition of a third filter, of course, scarcely can affect the situation.

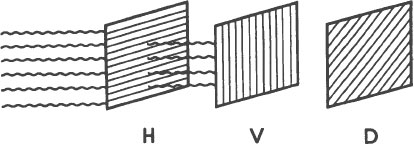

In a similar manner, if we place the diagonal polarizer on the other side of the horizontal-vertical combination, nothing happens. No light gets through the filters.

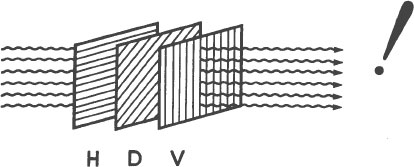

Now we come to the interesting part. Put the diagonal polarizer

between

the horizontal polarizer and the vertical polarizer.

Light gets through the three filters when cut off!

In other words, a combination of horizontal and vertical polarizers is as much a barrier to light waves as a wooden door. A diagonal polarizer in front of or behind such a combination does not affect this phenomenon. However, if a diagonal polarizer is sandwiched

in between

the horizontal polarizer and the vertical polarizer, light gets through all three of them. Remove the diagonal polarizer and the light disappears again. It is blocked by the combination of horizontal and vertical polarizers.

Diagrammatically, the situation looks like this:

How can this happen? According to quantum mechanics, diagonally polarized light is not a

mixture

of horizontally polarized light and vertically polarized light. We cannot simply say that the horizontal components of the diagonally polarized light passed through the horizontal polarizer and the vertical components of the diagonally polarized light passed through the vertical polarizer. According to quantum mechanics, diagonally polarized light is a separate thing-in-itself. How can a separate thing-in-itself get through all three filters but not through two of them?

If we consider light as a particle phenomenon, this paradox becomes graphic

. Namely, how can

one photon

be broken down into a horizontally polarized component and a vertically polarized component? (By definition, it can’t.)

This paradox is at the heart of the difference between quantum logic and classical logic. It is caused by our thought processes which are following the rules of classical logic. Our intellect tells us that what we are seeing is impossible (after all, a single photon must be polarized one way or the other). Nonetheless, whenever we insert a diagonal polarizer between a horizontal polarizer and a vertical polarizer, we see light where there was none before. Our eyes are ignorant of the fact that what they are seeing is “impossible.” That is because experience does not follow the rules of classical logic. It follows the rules of quantum logic.

The thing-in-itselfness of diagonally polarized light reflects the true nature of

experience

. Our symbolic thought process imposes upon us the categories of “either-or.” It confronts us always with either this or that, or a mixture of this and that. It says that polarized light is either vertically polarized or horizontally polarized or a mixture of vertically and horizontally polarized light. Thus are the rules of classi

cal logic, the rules of

symbols

. In the realm of

experience

, nothing is either this or that. There is always at least one more alternative, and often an unlimited number of them.

Finkelstein put it this way in reference to quantum theory:

There are no waves in the game. The equation that the game obeys is a wave equation, but there are no waves running around. (This is one of the mountains of quantum mechanics.) There are no particles running around either. What’s running around are quanta, the third alternative.

10

To be less abstract, imagine that we have two different pieces from a chess set, say a bishop and a pawn. If these macroscopic chess pieces followed the same rules as quantum phenomena, we would not be able to say that there is nothing between being either a bishop or a pawn. Between the extremes of “bishop” and “pawn” is a creature called a “bishawn.” A “bishawn” is neither a bishop nor a pawn nor is it half a bishop and half a pawn glued together. A “bishawn” is a separate thing-in-itself. It cannot be separated into its pawn component and its bishop component any more than a puppy which is half collie and half German shepherd can be separated into its collie “component” and its German shepherd “component.”

There is more than one type of “bishawn” between the extremes of bishop and pawn. The bishawn that we have been describing is one-half part bishop and one-half part pawn. Another type of bishawn is one-third part bishop and two-thirds part pawn. Still another type of bishawn is three-fourths part bishop and one-fourth part pawn. In fact, for every possible proportion of parts bishop to parts pawn there exists a bishawn which is quite distinct from all the others.

A “bishawn” is what physicists call a coherent superposition. A “superposition” is one thing (or more) imposed on another. A double exposure, the bane of careless photographers, is a superposition of one photograph on another. A coherent superposition, however, is not simply the superposition of one thing on another.

A coherent superposition is a thing-in-itself which is as distinct from its components as its components are from each other

.

Diagonally polarized light is a coherent superposition of horizontally polarized light and vertically polarized light. Quantum physics abounds with coherent superpositions. In fact, coherent superpositions are at the heart of the mathematics of quantum mechanics. Wave functions are coherent superpositions.

Every quantum mechanical experiment has an observed system. Every observed system has an associated wave function. The wave function of a particular observed system (like a photon) is the coherent superposition of all the possible results of an interaction between the observed system and a measuring system (like a photographic plate). The development in time of this coherent superposition of possibilities is described by Schrödinger’s wave equation. Using this equation, we can calculate the form of this thing-in-itself, this coherent superposition of possibilities which we call a wave function, for any given time. Having done

that

, we then can calculate the

probability

of each possibility contained in the wave function at that particular time. This gives us a probability function, which is not the same as a wave function, but is calculated from a wave function. In a nutshell, that is the mathematics of quantum physics.

In other words, in the mathematical formulations of quantum theory nothing is either “this” or “that” with nothing in between. Graduate students in physics routinely learn the mathematical technique of superimposing every “this” on every “that” in such a way that the result is neither the original “this” nor the original “that,” but an entirely new thing called a coherent superposition of the two.

According to Finkelstein, one of the major conceptual difficulties of quantum mechanics is the false idea that these wave functions (coherent superpositions) are real

things

which develop, collapse, etc. On the other hand, the idea that coherent superpositions are pure abstractions which represent nothing that we encounter in our daily lives also is incorrect. They reflect the nature of

experience

.

How do coherent superpositions reflect experience? Pure experience is never restricted to merely two possibilities. Our

conceptualization

of a given situation may create the illusion that each dilemma has only two horns, but this illusion is caused by assuming that experience

is bound by the same rules as symbols. In the world of symbols, everything is either this or that. In the world of experience there are more alternatives available.

For example, consider the judge who must try his own son in a court of law. The law allows only two verdicts: “He is guilty” and “He is innocent.” For the judge, however, there is another possible verdict, namely, “He is my son.” The fact that we prohibit judges from trying cases in which they have a personal interest is a tacit admission that experience is not limited to the categorical alternatives of “guilty” and “innocent” (or “good” and “bad,” etc.). Only in the realm of symbols is the choice so clear.

During the Lebanese civil war, a story goes, a visiting American was stopped by a group of masked gunmen. One wrong word could cost him his life.

“Are you Christian or Moslem?” they asked.

“I am a

tourist!

” he cried.

The way that we pose our questions often illusorily limits our responses. In this case, the visitor’s fear for his life broke through this illusion. Similarly, the way that we

think our thoughts

illusorily limits us to a perspective of either/or. Experience itself is never so limited. There is always an alternative between every “this” and every “that.” The recognition of this quality of experience is an integral part of quantum logic.

Physicists engage in a particular kind of dance which is foreign to most of us. Being around them for any length of time is like entering another culture. Within this culture every statement is subject to the challenge, “Prove it!”

When we tell a friend, “I feel great this morning,” we do not expect him to say, “Prove it.” However, when a physicist says, “Experience is not bound by the same rules as symbols,” he invites a chorus of “Prove it’s. Until he can do this, he must preface his remarks with, “It is my opinion that…” Physicists are not very impressed with opinions. Unfortunately, this sometimes makes them narrow-minded

to an extraordinary degree. If you are not willing to follow

their

dance, they won’t dance with you.

Their dance requires a “proof” for every assertion. A “proof” does not verify that an assertion is “true” (that that is the way the world really is). A scientific “proof” is a mathematical demonstration that the assertion in question is logically consistent. In the realm of pure mathematics, an assertion may have no relevance to experience at all. Nonetheless, if it is accompanied by a self-consistent “proof” it is accepted. If it is not, it is rejected. The same is true of physics except that the science of physics imposes the additional requirement that the assertion relate to physical reality.