The Book of New Family Traditions (5 page)

Read The Book of New Family Traditions Online

Authors: Meg Cox

Being a sometimes bossy and rather earnest person, it took me a while as a parent to learn the supreme importance of a sense of humor in creating family traditions—along with the necessity of just rolling with the punches, whatever happens.

In family ritual, perfection is the enemy. This is a very hard thing for a controlling person to accept, but I have learned the hard way. The goal is to have your family traditions be more like a wildly original, outside-the-lines crayon drawing than a formally posed studio photograph in which nobody cracks a smile. Rituals are homemade and hand-crafted, not something made by factory robots, and they should look and taste and feel DIY (do-it-yourself), with everything that implies.

It turns out that the more outrageously imperfect a ritual is, the more kids love it and remember it. The family party your children never stop talking about is the one when the dog ate the cake. In one family I interviewed, in which the mom always hides treats before the weekly family meeting (the kids have to hunt them as part of the meeting ritual), the kids are still laughing about the time she forgot that she hid the cupcakes in the washing machine-and threw the clothes in on top of them.

I will never forget when my yoga teacher from the YWCA invited me to a simple coming-into-womanhood ritual for her teenage daughter. It was a potluck lunch, and we brought small gifts for the girl. Flowers that people brought were woven into a garland for her hair. Later, family and friends waited in the backyard for my friend and her daughter to come out onto the deck and say a few words. It was clear they were both nervous, especially the girl, who was shy by nature. I believe she was afraid to make a mistake, awkward partly because they were improvising as they went.

Suddenly, one of the two let loose with a very loud fart (they won’t say who was responsible). Instantly, everyone present broke out laughing and the girl and her mother just leaned into each other, laughing hysterically. The tension was broken, and we could all let go and fully appreciate the moment and each other.

I hope you’ll remember many of the principles from this book, but especially, I hope you won’t forget the fart story. Anytime you find yourself getting all pompous about your big occasion or snapping at your kids because you are getting stressed about whether the turkey will be done at the same moment as the trimmings, do something just for laughs. I mean it! Break an egg on the floor, if you have to. Get everyone to bang pots with spoons to release tension, sing the silliest song you know in the loudest voice you’ve got. Get goofy.

Mischief managed.

CHAPTER 2

Everyday Rituals

Daily Rituals

The most vitally important rituals you can practice with your family are the ones you perform every single day. This consistency is especially important for infants and young toddlers: One day is endless for them, and the world is vast and unfamiliar. Being able to trust that certain things will happen each day at regular times in a certain order provides them with immense comfort. Ritual is an anchor, a home base.

But daily connections also keep older children, even teenagers, connected to their comfort zones, bringing them back to the safe haven that stays familiar as they change beyond all recognition. These rituals must grow and change to accommodate their new schedules and tastes, but I’m far from the first parent to notice that when you create a calm, steady zone inside a hectic life, kids are able to share all sorts of unexpected things. As they mature, they bring new things to the table—both literally and figuratively.

Mealtimes

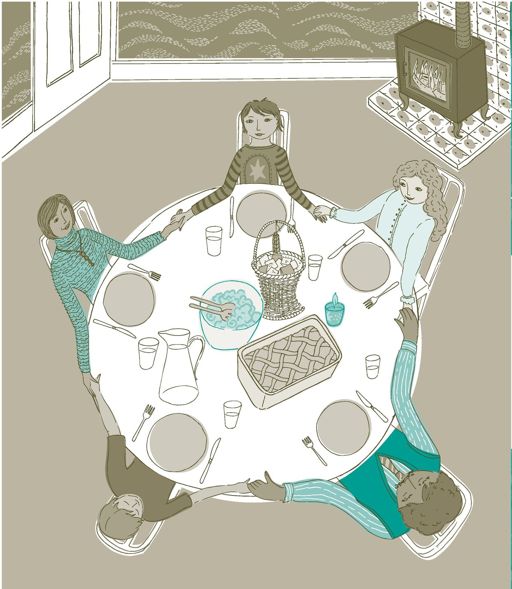

Let’s start with the ritual of daily meals. In some cultures, the simple ceremony of sharing a meal with someone makes you part of the tribe, and it’s impossible to overstate the importance of regular meals together as a family.

Obviously, conflicting work and school schedules can make this difficult, but do whatever you can to sit down and eat together as often as possible—even if that means that your “together meal” is a snack before bedtime.

To be effective as ritual, family meals need to focus on quality as well as quantity. Michael Lewis, a psychologist who has spent years researching American family dinners, discovered most families spend between fifteen and twenty minutes at the table, and a good amount of that time is spent nagging and whining. When people don’t have a mouth too full of food to speak, many of the comments run along the lines of: “Please pass the butter,” and “Stop kicking your sister under the table.”

So, getting everyone to sit around the table together is just the first step. As I said in the previous section on the parts of a ritual, it helps set the mood if you do something to signal the start of a ritual and the transition from ordinary time.

There is a good reason the stretch of time before dinner in households with children is known as “arsenic hour”: Early evening is the time when tired, hungry kids (and often grown-ups) can become button-pushing cranky. Even if sibling battles aren’t escalating at this time, every family member has his or her head somewhere else entirely: on the easy hit missed at baseball practice, the train wreck of a meeting at work, the daunting homework ahead, or that text message that just has to be sent to a BFF (best friends forever) right this second, or the world will come to an end.

Creating a dinner-is-starting signal is a great way to get everyone to change gears and refocus on the home team. This can be something incredibly simple such as ringing a bell or chime, turning the lights down, lighting a candle, putting on the local jazz radio station. You can say grace, hold hands, or say a one-sentence phrase in unison (even better if it’s a silly nonsense phrase that only means something to your brood).

Once the actual ritual of the meal begins, you’ll want some strategies to liven up the event, get the conversational juice flowing, and make sure the meal doesn’t devolve into a nag-fest on table manners. But first, some helpful ideas about getting started, for families that begin the meal with a blessing of some sort.

Grace

Even for families that aren’t religious, saying grace before a meal can be a wonderful ritual of transition. It functions like a call to reconnection after a day of separation.

Simple and Good

Some of the most profound graces are the simplest, such as the lovely Quaker grace “Us and this: God bless.” I also like: “Now my plate is full, but soon it will be gone. Thank you for my food, and please help those with none.”

Simplest of All: A Collective Pause

Amanda Soule, a mother of five who homeschools in Maine and writes the hugely popular SouleMama blog, says her family’s mealtime blessing is extremely important. “Once everyone gets to the table, we just pause and hold hands and take a breath together. It’s a really simple tiny thing that feels huge. This pause before the chaos resumes makes us all fully present and aware in the moment we are sharing together.”

Sing for Your Supper

The Hodge family sings together often, including for grace. A favorite is the Johnny Appleseed song that goes: “The Lord is good to me, and so I thank the Lord / For giving me the things I need / like the sun and the rain and the appleseed / The Lord is good to me. Amen.”

Holding Hands

The Michaels of Minneapolis say a simple grace, and then all squeeze hands before they eat.

Taking Turns

The Mowbrays take turns saying grace. Often they improvise, but in a pinch they keep returning to a traditional Christian blessing, “Bless us, 0 Lord, and these thy gifts, which we are about to receive from your bounty. Through Christ our Lord, Amen.”

Buddhist Blessing

Karly Randolph Pitman, a mother of four in Bozeman, Montana, often does a variation on a Buddhist loving kindness blessing. It has three parts, and the Pitmans say each line together: “May I be happy, may I be healthy, may I be peaceful, may I be true.” The second time through, they substitute “you” and look at the others while saying it: “May

you

be happy....” The third time, they all chime in: “May everyone be happy,” and so on, extending their blessing to the whole world.

Choosing a Grace

Two terrific books are

A Grateful Heart: Daily Blessings for the Evening Meal from Buddha to the Beatles,

edited by M. J. Ryan, and

Bless This Food: Ancient and Contemporary Graces from Around the World,

by Adrian Butash. Both provide many blessings and draw from a wide range of religions and regions.

Tip Box for New Parents: Rituals and Rules Are Sometimes the Same

When it comes to setting rules and rituals for every day, make this your mantra: It is far easier to turn a long-standing No into a once-in-a-blue moon Yes, than the other way around. Make strict rules about no screens at the table, no watching TV while eating, no staying up late, homework first after school, and so forth. Kids quickly get used to the limits you set, even find them comforting (but don’t expect them to say so). Then when you bend those rules for a meal or a day, it will be a huge treat. Just eating finger foods on a picnic blanket in front of the TV will be a major occasion. Think about it: If they can do anything they want, all the time, nothing is special and everything is chaos. Then, if you try to push back and set limits later, they will fight you every inch of the way.

Dinner Family Traditions

With a little planning and prodding, even hungry, preoccupied kids can make sparkling conversation.

Family News

Patrice Kyger insists that her children each share a “new and good” that happened to them during the day. Complaints and bad news are allowed, but never without the compensating good news. The Kygers are also on the lookout for what they call “blurbs,” random comments that strike everyone but the speaker as out of context and hilarious: These are written down in a special book.

Dinner Toasts

Amy Milne and her family clink glasses and make a toast at every dinner. “Sometimes it’s as simple as saying ‘To us,’ while other times we are honoring a special occasion,” says Amy, whose family lives in Asheville, North Carolina. “My parents always had a ritual to light the candles at dinner every night when I was growing up, and we had a candelabra on the table. The idea is to have something we do over and over, at home or in a restaurant, to celebrate that we are together. We taught the kids to always have eye contact while clinking.”

One, Two, Three ... Whine!

Courtney Andelman got tired of complaints about the menu and such. When the moaning begins, she simply calls for communal whining so everyone can get it off their chests. She says, “Let’s all whine at the same time, here we go! One, two, three ... waaaaaaaah!” Then everyone at the table laughs—and eats her food.

Current Events

Gloria Uhler’s kids had to come to the dinner table nightly with one topic of conversation related to current events. The rule was that all the children introduced their subject and shared some information they had heard or read. Everyone else in the family had to ask at least one question to keep the conversation going. If every night won’t work for you, try this as a weekly event.

Thankfuls and Untkankfuls

At dinner, Elizabeth Elkin always goes around the table and has everyone share a “thankful,” which means something simple like a good grade or a sunny day. Often her two boys have three or four thankfuls to share. In cases where they are especially glum and can’t think of any, she will do a round of “unthankfuls,” but she refuses to leave it at that. “I start asking them: Do you have a roof over your head? Do you have food to eat? Do you have a family that loves you? They quickly get the point. As a breast cancer survivor, I often give thanks for health.” Sometimes kids need both a good model, and a pointed prompt.

Conversation Basket

This was a real help in getting fun conversations going at my house. I decorated a small basket with ribbons and bought beads with letters on them. I spelled out the word

talk

and strung it on three ribbons, and then attached them across the handle of the basket, so they dangled down. When the basket is placed on the table at dinner, the ribbons ripple and sway, so it seems as if they are speaking the words to us, inviting us: “Talk, talk, talk” they say.

I cut pastel-colored paper into strips about two inches wide and wrote fifty different comments, questions, or instructions on them. Then I folded each one and piled them all in the basket, so we could take turns at dinner picking one. Often, we all wanted to respond to the query one person got, so we would each chime in on such questions as: “If a holiday were named after you, how would people celebrate?” and “Make up a nickname for everyone at the table, including yourself (nothing mean).” Another favorite was: “Tell us something you can do better than your parents.”